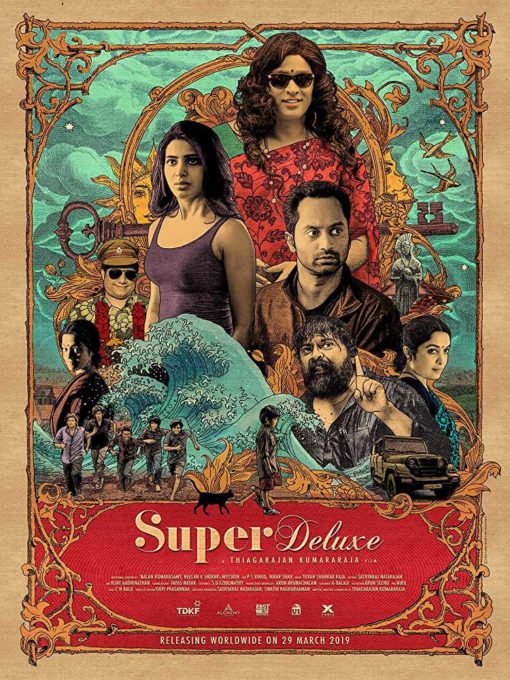

Film Poster|Image Courtesy: IMDb

Film Poster|Image Courtesy: IMDb

The Vijay Sethupathi starrer Super Deluxe feels like a lucid dream in a riot of eye-popping colours. Mercurial characters and humour that is pitch dark, offset by glorious cinematography, offers the film a dream-like logic all its own.

Sethupathi plays a trans-woman who returns to a conservative household where she left behind a wife, son and an endless supply of relatives, eight years ago. Fahad Faasil’s Mukil is an aloof husband and an aspiring actor. He winds up using his actor training to unburden to a corpse. Samantha, who was forced into marriage with him, finds an afternoon with a secret lover turn into gallows comedy. Four teenage friends who only wanted to watch a porn film find themselves involved with a gangster named Idi Ameen. Each have sinned and have been sinned against. There are aliens with electric blue eyes and unhinged faith healers. Their stories bleed into each other’s with the slow madness of fevered delirium.

This is the dream room where retribution slinks out of the dark and demands your deepest fear as the price of redemption, or from those who are irredeemable, just a price. It is the night terror where women find themselves powerless, cornered by what we dread the most– a predatorial man and no chance of escape. Screen-writer and director Thiagarajan Kumararaja flushes out the depths of human depravity into a bizarre world, painted in carnivalesque garishness. It is the real world reflected in a fun-house mirror. Twisted, frightening and explosively comical, there’s nothing in the mirror that doesn’t exist in our waking hours – murder, cowardice, sexual predation, misogyny, and transphobia, but also steadfast love, loyalty and acceptance.

Kumararaja peels away the false morality around sex and desire, while unmasking the keepers of respectability as either predators or hypocrites. Sin is a preoccupation in this film. Sometimes this concern is practically biblical. “The wages of sin is death”, but some are granted absolution. Others are made to unravel until they see their own pretensions of piety. These characters have limited mobility in their choices and even then they’re repeatedly stymied by their surreal situations.

There is genius and deep empathy in this film. But there is one aspect that enters hotly debated territory: should cisgender, heterosexual characters be playing LGBTQ+ characters? Should they especially do so when often these roles tend to become career defining, reaping for them both critical praise and awards, while queer/trans/gay actors lack representation in the industry? Hollywood is full of examples when cis-het actors have walked off with Oscars for portraying LGBTQ+ characters. Eddie Redmayne was nominated for Best Actor in The Danish Girl. Brokeback Mountain picked up three Oscars. None of these actors have had to live the trauma of homophobia or transphobia, yet it is those portrayals of LGBTQ+ lives that wins them the praise and awards. “Putting straight people in these roles paints queerness as a costume” is a fair argument. But it is also true that films like Moonlight have meant a tremendous deal for the queer community for its representation of masculinity, blackness and sexuality. The mainstream Tamil film industry hardly has as many examples of representing LGBTQ+ issues, though independent filmmakers have been doing incredibly well at filling that lack.

It is hard to deny that Sethupathi’s acting is stellar. He brings an insight and sensitivity, sorely lacking in big-budget Tamil cinema. Fahad Faasil, Myshkin, Samantha Ruth Prabhu and Ramya Krishnan all stun with their performances. Myshkin’s unbalanced faith-healer seems to have descended into the film straight from the many prayer meetings held in Tamil Nadu by dubious pastors. It is delightful to watch Fahad reprise a Tamil-speaking role. His debut Tamil film, Velaikkaran, did reasonably well. The actor’s ability to pull off unusual characters in Malayalam films, shines through here too.

Super Deluxe is in many ways surprisingly progressive for a mainstream Tamil film. Too often Indian cinema is guilty of skewed and phobic representations of non-cishet characters. But inclusivity needs to go beyond the film plot. There needs to be more space for LGBTQ+ communities to tell their own stories.

Read More:

The Politics of Desire

Love in the time of Revolution: Reading Ania Loomba’s Revolutionary Desires