Pulayathara by Paul Chirakkarode (1939-2008) explains how different an idea 'home' is, for the Pulayas and Paraiyars of Kerala, the supposed 'lower' castes of the land. 'Home', for them, is an ever changing, fragile, and ambiguous entity, for it is where their 'upper' caste 'masters' permit it to exist. 'Roots' then, in this context, becomes a symbol of privilege, for the feeling of 'rootedness' would only be possible for the one with a fixed home. The book takes us through the life of Thevan Pulayan, as it moves through the tumultuous story of his displacement and loss of identity. A man so attached to 'his' land and the fields that he worked on, his lifestory is placed on the background of fissuring paddy fields that have dried up because of scanty rains in the month of Makaram. One of the earliest Dalit writers in Malayalam, Paul Chirakkarode's work also tells us how the lives of 'untouchables' have not been very different for the Christian converts among them either. Although allowed to set up homes on Church-sanctioned land, their lives were still controlled by the 'upper caste' Christians around them. Furthermore, Chirakkarode adds how the land sanctioned to the Pulayas were spatially separated from where the upper castes lived, leading to their inevitable ghettoisation in Kerala's geo-cultural landscape. All of it seem to have made 'home' a site of oppression and subjugation – often just an idea, not physically existent – for the Pulayas and Paraiyars, writes the translator of the text Catherine Thankamma in the Introduction, communities that are still largely considered 'untouchables' in present-day Malayali society, making it a significant text of and for the times.

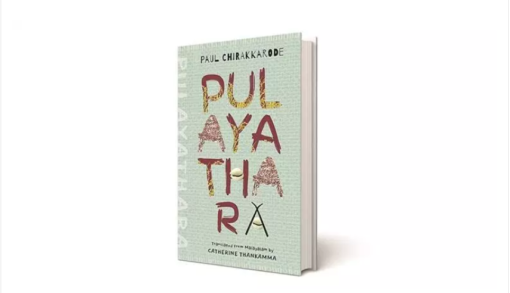

The following are some crucial excerpts from the Introduction, and chapters 'Heartbreak' and 'Yearning' of Pulayathara by Paul Chirakkarode, translated from Malayalam by Catherine Thankamma.

Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

Home is not just a place of habitation. It is an idea, a concept deeply embedded in our collective unconscious ever since human beings gave up a nomadic way of life for a settled one. The idea of home is one that simultaneously represents physiological, psychological, and social needs. The Malayalam word thara can variously mean floor, platform, foundation, and home. For the Pulayar and Parayar, two Dalit castes of Kerala, thara was often a 36-square-foot raised mud platform enclosed by a framework made by binding together whole/slit bamboo poles and thick ribs of coconut branches, the walls and roof covered with woven coconut sheaves. To this they would return after the day’s hard labour, to rest their aching bones till dawn. For these repressed people—who hardly had any aspirations and which, if they dared to have any, were hardly ever realized—thara should have been an asylum, a sanctuary. However, in the caste-determined feudalistic social fabric, even the surety of a home was denied to the so-called untouchable castes. Pulayathara (1962) depicts how the socially sanctioned substantive inequality that existed in nineteenth-century Kerala turned ‘home’ into a site of oppression and subjugation.

[…]

The time for harvest had arrived. The green paddy fields acquired a golden hue from the grain that adorned each plant. From the slope of the hill on which the Church stood, the cluster of fields lay outspread, a vast expanse. The early morning sun dripped more gold on the golden rows of grain. The dark-skinned women, carrying newly sharpened sickles, could be seen moving in a line along the edge of the fields. Thevan Pulayan stood in the Pallithara yard and watched. He felt a sharp stab of pain as though a dagger had pierced his chest. The paddy field that lay snug on the other side of the line of fields was Narayanan Nair’s, Thevan Pulayan’s merciless Tham’ran’s.

Thevan was the one who had built its boundary, plied the seven-leafed wheel to dry out the excess water, and sowed the seeds. His sweat had fallen on that soil, drop by drop. His soul that had been plucked out and thrown away from that field was striking against its skeletal frame, crying to be let out.

‘Eda k’datha, Kandankora,’ Thevan Pulayan turned towards the house and called.

Kandankoran reached his Achan’s side. The older Pulayan said, a sob in his voice, ‘Eda k’datha, harvest has begun.’

‘Hmm.’ A deep grunt. Kandankoran felt a grief-stricken sigh stifle his chest. He, too, was chewing down the pain.

Thevan Pulayan said, ‘Eda k’datha, they must be harvesting our field too.’ Kunjol Velathan and son Azhakan, who were tenanting Anjilthara, must be moving towards the field now. He must reach there before that. Thevan was the one who sowed that field. The right to cut the first grain-laden shoot was his. He would not allow another to usurp that right.

‘I’ll go there and be back soon.’

Kandankora stopped him. Thevan would be inviting danger if he went there. Thevan Pulayan would not stand on the side and look on. He would enter the fi eld and harvest. Thampuran would then use his stick on him. As the picture rose in his mind, Kandankoran felt a flash of fear. In earlier times workers often suffered the beatings of landlords.

‘Acha, don’t go.’

Thevan Pulayan experienced the agony that the soul of an imprisoned man feels. Kandankoran stood by silently. Life had no stability anywhere. It shifted beneath their feet. In those aimless lives, defeats outnumbered everything else. There might have been others among Thevan Pulayan’s ancestors who had been thrown out of their homes in the same manner. Even then they had continued to serve the landlords. They showed great enthusiasm in seeing the landlord’s granary fi ll with grain. Even as they worked themselves to death, the landlords grew stout. But they forgot that another generation had sprung from among the low castes and was growing up.

Unknown to Kandankoran, Thevan Pulayan went to the field. He walked fast—past Anjilthara, past the outer fence—but his legs were trembling. The tremor spread all through his body. Was that resistance? Maybe. It could also be the weight of humiliation. The western wind blew in from Aayirampara field. Thevan Pulayan inhaled deeply. As he inhaled the air, he felt a new life enter him.

People were already lined up in the field. Kunjolu Velathan from Anjilthara cut the first crop. The others too began to reap and move forward. Thevan Pulayan could not bear to watch it. The old Pulayan turned and walked back.

[…]

Suddenly a child came running towards them. He said, ‘Achan has asked for Paulos and Pallithara Pathros. He wants you to see him immediately.’

Pallithara Pathros asked, ‘Who all are there at the Mission bungalow?’

‘Achan, Custodian Thomas, and some other people.’ Paulos looked at Pallithara Pathros meaningfully.

‘It must be to tell us not to hold the meeting,’ said a youngster.

Another agreed and added, ‘What the Custodian went about saying must be true.’

In their hearts everyone was afraid. But no one admitted it. They spent some time dithering. Finally Paulos said, ‘Let Achan resist us, let the Custodian resist us, we will hold this meeting.’

His words sounded like a soldier’s battle call. The others gained courage from it.

‘Yes, we will hold this meeting!’ They echoed his words.

The words struck the walls of the Church and reverberated. It was the echo of the new generation awakening. As it struck, the foundation of the Hilltop Church shook. The tremor was strong. Paulos and the others entered the priest’s bungalow. They stood in the attractive room bathed in the light of an electric lamp. There seemed to be quite a few people there. Custodian Thomas sat next to the priest. At that moment, for some reason, Paulos thought of Archangel Gabriel who sat next to God. As he thought of it, a grin appeared on Paulos’s face.

Achan looked at them closely through his shining spectacles.

Then he lowered his head and sat silently. After a while Paulos said, ‘We have come, Acho.’

Courage echoed in those words, the courage of a community that had become enlightened. It created waves in the acquisitive mindset that fi lled that attractive room.

‘A command has been issued by the higher Church. You cannot hold your meeting,’ Achan said regretfully.

So they could not speak about the grievances that they suffered? What other place was there where they could proclaim it all?

A terrible urge to challenge sprang up within him, but Pathros controlled it. He asked quietly, ‘Why, Acho?’

Custodian Thomas was furious. He said, ‘Look, just look at his audacity. Eda, I will tell you. Your ways are against the Lord. You are going towards Satan’s side. The communists here are aiding you. So …’ He paused, cleared his throat, and said with the intolerance of the believer, ‘We will not allow you to hold the meeting. It is a shame for us. And the authorities are on our side!’

Paulos asked: ‘Who are these us and you?’

At last, the division was out into the open! Caste difference had been expressed openly. However much you sang and prayed, the barrier of caste continued. It would not die.