Film Poster, Kumbalangi Nights|Image Courtesy: IMDb

From revenge fantasy to the ludicrous performance of “manhood”, what Syam Pushkaran undertook in Maheshinte Prathikaaram (2016), he does perfectly in Kumbalangi Nights (2019). These are the National Film Award winning screenwriter’s two solo writing credits. Both feature Fahadh Faasil, who is fast becoming a star actor.

Pushkaran wrote toxic masculinity as a sort of obsessive madness in Maheshinte Prathikaaram, which he edges with humour at the expense of the men. Mahesh (Fahadh Faasil), who usually stays away from falling into gendered male tropes, takes a beating while trying to break up a fight. There is a sequence in which Mahesh feels pressured to respond like cine-heroes do, to leap to his feat theatrically retying his mundu, to land an even harder blow than what knocked him down. He fails spectacularly and winds up badly hurt and defeated. He takes a “solemn vow” to not wear slippers until he’s fought the other man again and won. It isn’t endearing eccentricity. It is ridiculous obsession that is laughable and yet, laced with malice. Unfortunately Maheshinte Prathikaaram fulfills the revenge-drama formula as Pushkaran himself admits. There is an attmept to parody climax scenes that involve the hero and villain brawling on the ground in muck. Two women observe dispassionately to each other that men are all mad, yet it takes a confused position.

The warrior male trope —drenched in blood and mud, fighting for dominance; the hero’s claim to rightness and correcting an injustice by the villain that can only be legitimised when he delivers the final blow. Even though Maheshinte Prathikaaram attempts to mock that, it doesn’t quite manage to extricate itself from the silliness and rank masculinity it represents.

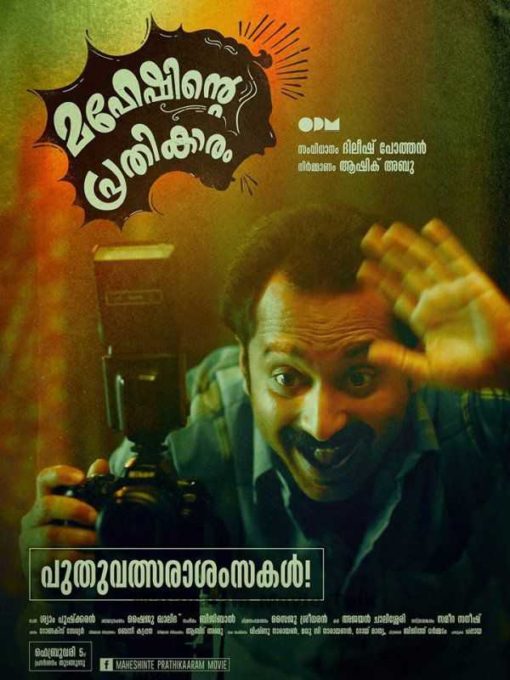

Film Poster, Maheshinte Prathikaaram|Image Courtesy: IMDb

Film Poster, Maheshinte Prathikaaram|Image Courtesy: IMDb

Which is why Fahadh’s character (Shammy) in Kumbalangi Nights in an impressive feat of screen-writing. Shammy is the kind of man that nearly all women have had to deal with: pompous, self-righteous to the point of delusion, overbearing, pious about everybody else’s actions. He has a staggering sense of conviction about his good-looks and is stomach-turningly sleazy. The kind of man who cloaks emotional abuse as being “protective”. He swaggers around his wife’s house that he’s moved into and completely takes over the lives of her mother and younger sister. He uses slick affection to enforce his place as the man of the house in her dead father’s stead. All decisions flow through him, he is “relieving his old mother-in-law of responsibilities”, “dotes on his wife” and “is treating the younger sister as his own” — all euphemisms he employs to micro-manage each of them. He always wants respect, so disagreeing with him is of course interpreted as disrespect. He is the man who’s used to having his way. He believes he has an ironwill. What it really means is that he is so fragile that the first time his wife defies him, it renders him catatonic. In an absurdist sequence of events, Shammy walks up to a corner of the house, stands facing the wall and goes immobile wearing a vaguely sinister smile, while everyone around him is thoroughly unnerved. He then descends into full-blown manic violence. Shammy is not Arjun Reddy/Kabir Singh. There is no one gushing to condone him. He isn’t condoned. He is discarded and left alone.

Shammy is only one character among a set of finely thought out men and women in Kumbalangi Nights. The men are expected to take collective responsibility of male toxicity, if they don’t identify with it. They aren’t excused simply because they don’t personally abide by it. Even then, they are far from exemplary people.

Pushkaran also deals with the complexities of kinship, rejecting the idea that the institution of family is built on blood and conventional ties. It rejects, at once, gendered manhood and “respectability”. Deliberately contrary to middle class values, home is instead a struggling alliance of individuals sometimes disgruntled with each other, who have no bonds that “respectable” society endorses, but nevertheless choose to be bound to each other.

A smallish derelict house by the backwater inhabited by half-brothers and step-brothers, Bobby, Saji, Boney and Franky is the dysfunctional, beating heart of the film. What is challenged here though, inspite of the comical fall-outs they have with each other, is the notion that their inability to function like “normal” families is a flaw that will eventually be corrected. Shammy’s household that has all the trappings of propriety is where something irredeemable lives, carefully hidden behind immaculate walls and uncontroversial relationships.The abuse by Shammy is of no consequence to the neighbourhood. The fact that Saji and Boney are brothers because two single parents married each other, is a constant source of contempt. The brothers’ household expands slowly, with lovers who take refuge, and the widowed wife of a friend with a new baby. This motely group isn’t trying to be radical and make a point. Their comming together isn’t a political act. They just are, as there such families everywhere, whatever the conservative idea of the family unit may be.

The film’s defiance is simple, real and everyday. It could be dismissed as basic and saccharine, but whoever does that needs to also check their privileges. Maheshinte Prathikaram has exceptional moments even though it fails to rise above certain elements. But those choices are also made by the director. In the three years between the release of the two films, Pushkaran’s desire to purge masculine violence through his screen-writting has shown remarkable progress. Kumbalangi Nights gives us almost pitch-perfect storytelling while prodding men to examine the violence within them.

Read More:

Why Kabir isn’t Cool

Intersectional Approaches to Addressing Gender, Religion, Culture: South India Focus

Aabhaasam: Democracy Travels at Night