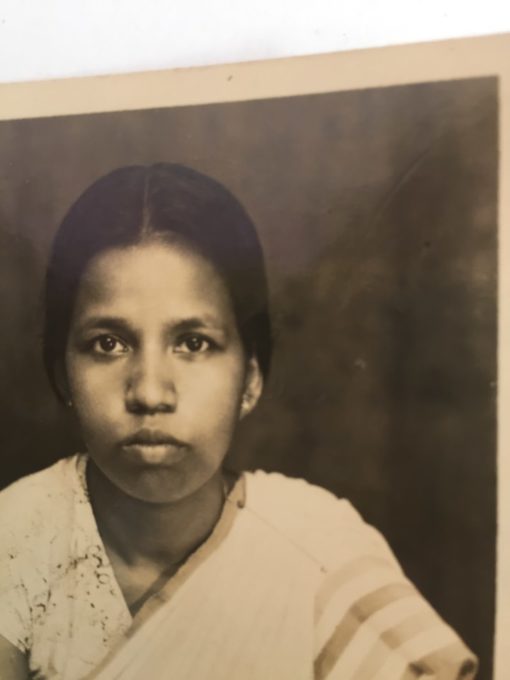

Dakshayani was born in 1912 at Bolghatty, a small island off the coast of the then princely state of Cochin, in an agrestic slave caste, ‘Pulaya’. She was the child of social change, for early 1900s saw some of the earliest of struggles for equality and recognition across Kerala. Significantly, it saw Ayyankali (1863-1941) lead anti-caste struggles for democratizing public spaces and for workers’ rights, a precursor to the formation of rural labour and working-class organizations in Kerala. Using the public road, riding on a bullock cart – Villuvandi – and wearing the traditional upper caste Nair attire, Ayyankali also started the ‘walk for freedom’ (the right to walk on public roads) in 1893 in Travancore’s Venganoor, to Puthen Market and at Chaliyar street facing resistance from an upper caste mob. It was as a result of this that Pulayas won the right to walk on public roads in most areas of the region by 1900, although there were many private and special roads that remained prohibited for them for many more years. These assertions led to the raising of other issues, with many more sub-caste organizations spontaneously emerging. A year-long agrarian strike demanding rights for education (1907-8), was followed by the call to women by Ayyankali to throw away their stone necklaces (‘Kallumala Agitation’, 1915-17), fight to cover their torso – both symbols of caste slavery.

Dakshayani writes

“I can’t say that I was born in a poor Pulaya family, as the family was not poor at the time of my birth. Unlike other Pulaya families in Cochin state, we had a house of our own and a compound of more than one acre, with coconut and other fruit trees. The family could live with the income from selling coconuts. My father was a village school teacher, i.e. he used to teach some children; our house was the school. He used to go for contract work of bunds, with the other male members of the family. My two elder brothers were the first in the community to crop their long, knotted hair and wear shirts. When they were on the road, people from other communities would hoot at them; when on the country boat, people would throw stones at them because they were “wore upper castes clothes”, i.e. mostly Latin Christians and Ezhavas… Soon, our house was mortgaged.”

Dakshayani’s narration of the formation of the ‘Pulaya Mahajana Sabha’, one of the earliest Pulaya groups, conveys the public practices and private experiences of anti-caste assertions:

“My two elder brothers and father Kunjan’s younger brother, Krishnethi (Krishnadiyasan, 1877-1937), Pundit Karruppan, and T.K. Krishna Menon of the Thottekal family, formed the Pulaya Mahajana Sabha, with Krishnethi as President. In Cochin, the Maharaja had prohibited the ‘untouchables’ from holding meetings on “his land”.

Therefore, meetings were held with country boats tied together in the sea at Bolghatty – for the sea did not have caste. The raft was made by joining a large number of catamarans, with the help of the fisherfolk. The Pulaya Mahajana Sabha took up important social issues in their meetings and Krishnethi was able to inform the Maharaja that he did not disobey his orders.

“My elder brothers were the first to crop their long hair and wear shirts. They were abused and stoned by those from the dominant communities of the region, Latin Christians and well-off Ezhavas.”

“My brothers and Krishnethi, who worked as petty contractors in the construction of the port and harbour, also composed songs and poems. One of the songs read, “If we go by road, they roll their eyes and try to scare us, if we go by boat, they throw stones at us….”

“Krishnethi and others also held meetings with the followers of Sree Narayana Guru. An agricultural exhibition was held in Ernakulam and a variety of grains were at display. Yet, the Pulayas, the producers of grain were not allowed to enter Ernakulam. My brothers and Krishnethi wrote an appeal to the Cochin Maharaja in poetry, following which we were allowed entry. My mother said that she entered Ernakulam for the first time along with others, led by Pandit Karuppan.”

The Many Firsts of Dakshayani’s Life

There were many firsts in Dakshayani’s life. As the first Dalit woman graduate in India, Dakshayani wrote about her higher education at Maharajas College in Ernakulam, Kochi:

“I had a brilliant educational career. I was the only female student in B.Sc Chemistry, or any science course at college. It was sheer luck to get higher education. Journalists wanted to photograph me as I entered college, for it was a first for my community. However, I entered without being noticed. They later found me in the chemistry laboratory.”

“I remember upper caste teacher was hesitant to teach me the experiments, so I had to learn by observing things from a distance. I however graduated in 1935 with high second class”.

“Two weeks after graduation, I applied for a teacher’s post, and in July 1935, I was posted as an L2 teacher in the High School, Peringothikara in the Trichur District. Peringothikara was selected by the Director of Public Instructions, late Shri I. N. Menon, as it was predominantly an Ezhava-dominated area and caste-based discrimination was far less severe here. Most Ezhavas there were very well-educated and enlightened.”

Seeing the Ezhavas practice witchcraft, Dakshayani remarked: “The Ezhavas in my neighbourhood are not so enlightened”

“My domestic help is a girl who belong to the Vettuvan caste, and I am a Pulaya. Neither of us could draw water from the well, but the problem was solved by the presence of my mother, as she had the privilege which I and the girl did not have, because my mother was a Christian convert”.

There were assertions too – “One day when I was going to teach at the school, which was a two-minute walk from the house, I met a Nair woman, who lived next to the school. All along the road from the residence to the school, there were paddy fields on both sides. The Nair woman asked me to make way for her to pass by. I told her that if she wanted to walk by, she should get down onto the field. The field was 4-5 feet below the level of the road. As I did not concede to her demand to make way for her, she had to listen to me.”

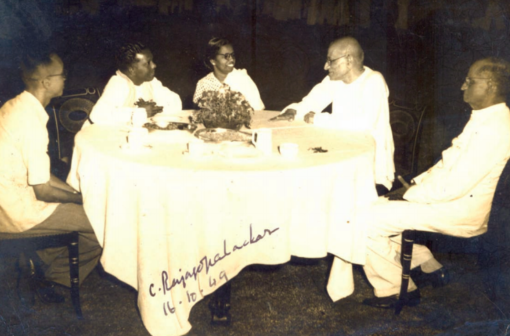

Titled ‘Down Memory Lane of Politics’, in the work on her political journey, her nomination to the Cochin Legislative Council (1945) and Constituent Assembly election (1946) are called “interesting and historical”.

“The Cochin government used to nominate one person from the scheduled castes as member of the Cochin Legislative Council. I wondered why I should not seek nomination. I was a high school teacher at the time. One day, I went to see the Minister for Rural Development, Dr. A.R. Menon, at Ernakulam. Cochin state had a partially responsible government at the time. Without offering me a seat, I was told that my nomination to the Legislative Council was not possible, as I was a government servant – an idea he was not comfortable with. I had to resign from my post, which I was not prepared to do, MLCs did not receive any income those days. However, when I was finally nominated to the Cochin Legislative Council, I was married and my husband was employed, making it affordable to resign”.

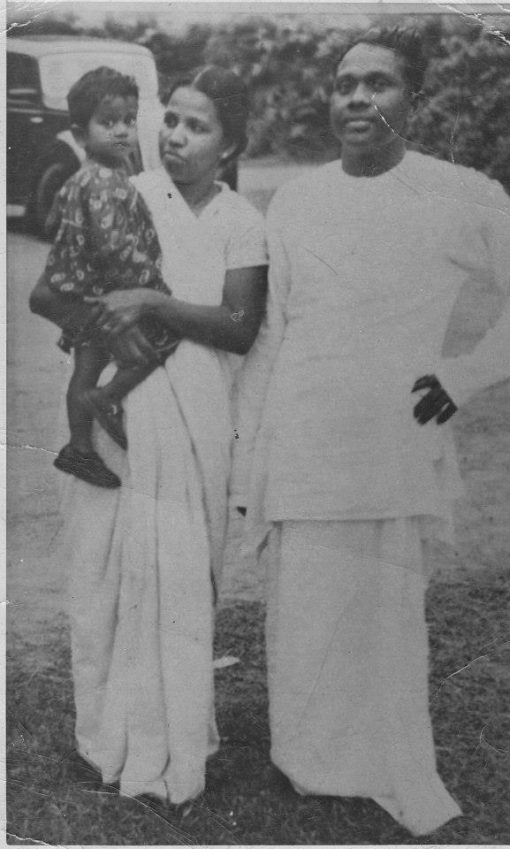

Wedding and Life in Gandhi’s Ashram

During the Working Committee meeting of the Indian National Conference, the wedding of Dakshayani and Shri R. Velayudhan was held, in the presence of Gandhi & Kasturba Gandhi, with a leper officiating as priest.

About life in Gandhi’s ashram, she recalls:

“One day, Gandhi, seeing that I was uncomfortable with the food at the ashram – chapatti and jaggary – asked jokingly whether I expected fish there. He added that we could cook non-vegetarian in our own huts, but not in the common kitchen. Since cooking with firewood in an ‘angithi’ made of mud was a hassle, I thought it better to bear with the common food”.

On August 2, 1945, Dakshayani spoke for first time in the Cochin Legislative Council, in English. Pointing out that the funds allocated for depressed classes were dwindling, she called for ‘Proportional Reservation’ at the panchayat and municipality. She also lashed out at the system of untouchability, calling it “inhuman”. Dakshayani said that as long as untouchability remained, the word ‘Harijan’ was meaningless.

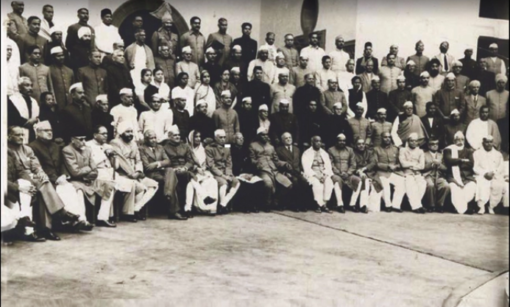

Member of the Constituent Assembly

There were just 15 women in the 389-member Constituent Assembly. She was the lone Dalit woman, and at 34-years old, perhaps among the youngest.

About her first speech in the Constituent Assembly (19th December 1946), she wrote:

“I spoke against separate electorates, against slave labour, and abolition of untouchability – saying that untouchability should be banned immediately through an ordinance. However, I was asked by the party – Indian National Congress (INC) – to withdraw it as it was soon going to be one of the articles of the Constitution”

Although a Gandhian, she was with B. R. Ambedkar’s take on many issues. On the draft Constitution, she expressed her appreciation while calling for greater decentralisation – She argued against the appointment of governors, as she thought there would be issues between a state government and a governor appointed by the party at the Centre. She also suggested that the final draft of the Constitution should be adopted following a ratification through general election. She again intervened during the discussion on Draft Article 11 (Art 17 of the Constitution), which aimed at abolishing discrimination based on caste, and making it punishable by law. She said, “We cannot expect a Constitution without a clause relating to untouchability”.

She also called for the implementation of provisions for non-discrimination in public education and thought that it would send a great message if the Constituent Assembly were to endorse a resolution condemning caste-based discrimination.

In her speech, she held that the Constituent Assembly should have gone beyond framing a Constitution, by “giving people a new framework for life”; use the opportunity to make untouchability illegal, and ensure “moral safeguards that would give real protection to the underdogs of India” (CA Debates,151-152).

Dakshayani’s idea of “moral safeguards” rested on the idea that only an independent socialist republic could remove social disabilities and offer civil liberties to every citizen. She added, “the working of the Constitution will depend on how people would conduct themselves in the future, not simply on the execution of the law. I hope that in the course of time, there will not be any community termed ‘the Untouchables”.

Her interventions in the Constituent Assembly were moulded by time she spent with both Gandhi and Ambedkar. From Editor at Gandhi Era Publications in early 1940s Madras, she went on to became editor of Jai Bheem, an Ambedkarite publication, also in Madras. Along with her husband R. Velayudhan, she was a member of the Provisional Parliament – perhaps the first Dalit couple from two opposition political parties. Velayudhan was with the Socialists led by Ram Mahohar Lohia, while Dakshayani remained with INC.

However, Dakshayani never joined the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) aligned with Indian National Congress post-independence, as to her, the AIWS was elitist in nature. Outside the Party, she worked among post-partition refugees and Tibetan refugees, for she was influenced by the Gandhian notion of constructive work. She then worked as an LIC Insurance officer in Delhi to support the family – five children and many other relatives – once her husband was elected as a Lok Sabha member to the first Parliament.

The 1970s saw a shift in the nature of Dakshayani’s engagement in politics, through the formation of a national platform for Dalit women. Cut off completely from her roots in Kerala, the sense of loss was deep, but she, along with few Ambedarite middle class women, organized a national conference of Dalit women and formed the Mahila Jagriti Parishad (MPJ) in 1977. The lively conference, with over 200 Dalit women from different states, with their own stories, poems, speeches and songs, reflected a desire to create a space of their own, nationally. The MPJ, with Dakshayani as President and Kaushalya Baisantry as General Secretary, began work among the women sweepers of South Delhi’s Munirka, by providing them basic literacy and training for alternate employment skills. Funds were out of question, and they worked according to Gandhian ethics of voluntarism and building resources from within.

Dakshayani Velayudhan passed away after a short illness on 20th July 1978. Although the MPJ petered out, the 1980s witnessed more such efforts by Dalit women in different parts of the country.