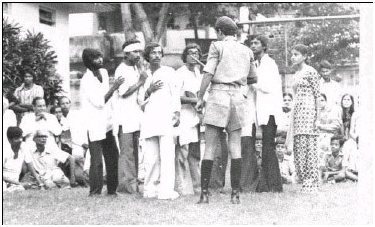

A scene from Badal Sircar’s Juloos, performed by a Patna-based theatre group in the 1970s. | Image courtesy PressReader

A scene from Badal Sircar’s Juloos, performed by a Patna-based theatre group in the 1970s. | Image courtesy PressReader

Theatre in independent India is a rich tapestry of practices, personalities and influences, with one name common to them all – Badal Sircar.1 Whether as a playwright whose oeuvre includes the most-performed works in the country; a thinker whose theories, like the Third Theatre, are still practised; or a pedagogue whose workshops have shaped many theatre practitioners, it is hard to think of any other figure who has had such a far-reaching and lasting influence.

Badal Sircar shot to prominence with his pathbreaking play Ebong Indrajit (And Indrajit, 1963) expressing a very contemporary existential angst and quest for meaning. Theatre stalwarts all over the country praised it. B. V. Karanth felt a strong bond with the play, claiming that it brought him recognition in Karnataka. Avant-garde Mumbai director Satyadev Dubey said that for him the play was an “obsession”, a lasting influence on his subsequent work. For Shyamanand Jalan the play’s philosophy and content became “very personal”; while Girish Karnad stated that Ebong Indrajit taught him about fluidity of structure.

However, although his subsequent plays like Baki Itihas (1965) and Pagla Ghora (1967) established him firmly as a leading playwright, Badal Sircar himself was rethinking proscenium theatre and the economy on which it was based — such as hired auditoriums and ticketed shows — and moving towards a different philosophy of theatre, based on direct communication between the actor and the audience: a theatre of intimacy and equality he felt was missing from the urban stage.

His concept of a “Third Theatre” was different from both the traditional folk forms (“First Theatre”), and the urban, westernized model (“Second Theatre”). Third Theatre was centred on the actor, and on the human connection: between actors themselves and between them and the audience; an honest, face-to-face communication without any distancing devices like the “fourth wall” of the proscenium stage, fixed seating with the audience in darkness, tickets, lights, sets, or scripted dialogue. Third Theatre was a collective process, its text developed through workshops. It was inexpensive, mobile and flexible, needing only the actor. It could be performed in places like community halls with a small audience sitting around – the anganmancha; or in outdoor public spaces such as parks for large audiences – the muktamancha. Any space could be claimed as a performance space by this theatre.

In terms of content, this was theatre as counter-culture, an exercise in awareness-raising, protest and political comment. “It drew on the daily reality of the common man, the violence, corruption, discrimination, power politics, struggle, disillusionment, persistent hope, battered idealism, confusion and questioning that all of us go through as we grapple with the everyday.”2

Third Theatre also focused on training the actor through intensive workshops. Communication was not about learning lines, but feeling and conveying the truth of the text which had been developed collectively. The actor’s body was her chief instrument – through movement, uttered sound, group choreography. The individual fused with the ensemble.

This was free theatre taken directly to the people; it was political in intent and effect, but it was also theatrically and aesthetically evolved, complex and layered. It lifted “street theatre” onto a higher plane. Young theatre workers struggling against financial scarcity found it wonderfully liberating and empowering – here was meaningful theatre that they could engage in anywhere, using just their minds and bodies. This became the real contribution of Third Theatre, and for this Badal Sircar is considered the father of street theatre in India.

Michhil (Juloos in Hindi), widely seen as Badal Sircar’s most iconic production, is an excellent example of Third Theatre. First produced in 1974, it is still performed in several languages, within India, across the subcontinent and even by the Indian diaspora abroad. Many typical features of Third Theatre are found in Michhil, such as intimacy and direct communication with the audience, satirically critical commentary on the status quo, the vision of a just and equitable society, a collage-like juxtaposition of sequences, the actors’ bodies forming a range of sculptural images, and humour.

From the very start there is no separation of performance and audience space. Actors perform from amidst the audience; it is hard to tell an actor from a spectator. The play begins with Khoka (“boy” in Bengali) entering the acting area and dropping dead with a scream, followed immediately by the Chorus bursting in and spreading out all over. Khoka dies over and over in the play. He tries in vain to get the Police officer to notice him. He speaks to the audience, “I was killed. I. Me…I was killed today. I was killed yesterday. I was killed the day before yesterday…Last week. Last month. Last year. I am killed every day.”3 He remains invisible as scenes from daily life materialise all around him, some drily tongue-in-cheek, some brutally violent, some broadly farcical. The actors constantly transform the performance space with their bodies to convey a street, a funeral procession, a train or bus full of vendors and passengers, a factory with machines, and so on. From communal clashes to profiteering to military transgressions, all kinds of corruption and injustice are portrayed for an audience that, just as it would on the streets, lines both sides of the path of the michhil as actors pass before them, urgently searching for the missing Khoka, or offering items for sale.

At the end, the Chorus winds its way through the audience, singing: “A song of hope. A song for the future… A song of dreams… The people in the procession are holding hands… The audience is invited to join.”4

Rustom Bharucha describes this as “one of Sircar”s most intricately structured plays, with innumerable transitions and juxtapositions. The relentless flow of events in the text is most skillfully concretized in the swirling movement of the mise en scene. The actors are constantly on the move – walking, running, dancing, and jogging . . . the effect is startling: one can almost see a procession winding its way around the streets of Calcutta.5 At the end, “The spectators and actors intermingle and the entire space of the room becomes a swirling mass of humanity. It is one of those moments in the theatre when one becomes acutely aware of the possibilities of life and the essential brotherhood of man. Transcending the immediate issues of the play, it lingers long after the play ceases, compelling the spectators to reexamine their affinities and responsibilities as members of a society.”6

Michhil and Badal Sircar are not just a part of theatre history. They remain extremely relevant today, a living influence. And Michhil, a favourite with youth and college groups, is an example of Third Theatre at its best.

1. Badal Sircar (1925-2011), playwright, director, received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1968, Padma Shri in 1972, and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship – Ratna Sadsya – in 1997. He declined the Padma Bhushan in 2010 saying he was already a Sahitya Akademi Fellow, the highest recognition for a writer. In 2011 The Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) honoured him with the META Life Time Achievement Award.

2. Anjum Katyal, Badal Sircar: Towards a Theatre of Conscience (New Delhi: Sage, 2015), p. xvii.

3. Badal Sircar, Three Plays (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2009), p.17.

4. Badal Sircar, Three Plays (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2009), p.53.

5. Rustom Bharucha, Rehearsals of Revolution: The Political Theater of Bengal (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1983), p.157.

6. Rustom Bharucha, Rehearsals of Revolution: The Political Theater of Bengal (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1983), p. 163.