On Monday, 5 August, the BJP Government abrogated Article 370, stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its statehood, further cementing military occupation and pushing an already brittle situation towards a volatile future. Amidst fears of bloodshed and long-lasting clashes between Kashmiris and the military, Aijaz Khan’s 2019 film Hamid seems an ideal film to revisit. Through the life of seven-year-old Hamid whose father has disappeared for a year, Khan tells the reality of life under occupation in the most densely militarised zone in the world.

Enforced Disappearances —a large number of them of young men and minors—are one of the many forms of human rights violations in J&K. Most of them do not even have connections to the armed opposition. Further, in May this year, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) released a joint report on “Torture: Indian State’s Instrument of Control in Indian Administered Jammu and Kashmir”. APDP states that in its 25 years of work, it has discovered close connections between enforced disappearances and torture. “There is a universal understanding that there is an extremely high probability that those who were disappeared by the State agents may have been subjected to extreme forms of torture. One cannot rule out the possibility that some of the disappeared may have lost their lives or live in the fear of losing their lives. Those resurfaced in other south Asian countries after being disappeared recount horrific memories of being tortured and living in perpetual fear of death”, APDP said in a statement made on 30 May, 2019, during the International Week of the Disappeared.

In the film, Hamid is a boat-maker’s son. As his father returns home one night, he is stopped and searched at a CRPF checkpoint. One of the jawans, Abhay rifles through his belongings and finds a notebook of poetry. He accuses Hamid’s father of writing “insurgent” literature, but the man insists that his writing isn’t political, but personal. He makes it home, still shaken and perturbed. At home, Hamid keeps asking for the cell he’d promised him. Attempting to placate the small child, he leaves for the workshop where he’d forgotten the cell he’d bought for him. He never returns. A year passes, Hamid asks about his father every day. His mother goes to the police station every day and waits with family members of others who’ve been disappeared hoping to meet the commissioner. Nothing changes.

Both mother and son are locked away within their own grief, hardly interacting. The mother seems to simmer with resentment towards Hamid, placing the responsibility of her loss on the boy who whined for his cell, rather than the oppressive state and military who took her husband from her. “She doesn’t even look at me”, Hamid observes. Perhaps he is an immediately available peg to place blame on and easily punish. The alternative after all is hostile forces around her, made visible only by barbed-wires, guns and suspicion.

A curious and inquisitive boy, Hamid decides to bring back his father whom he sorely misses. When a classmate tells him that his father is with Allah now, he takes it literally. “786 is Allah’s number”, he’s told. So he industriously works out that 9-786-786-786 would give him a ten digit mobile phone number to ring. He dials and within the film’s sense of irony, he connects with the same CRPF jawan his father had a run-in with. The boy believes that he has reached Allah himself and demands to know why he needs to keep his father away for so long. They strike up a friendship. Hamid with his charming manners quickly becomes someone Abhay cares for. Using this strange connection between a Kashmeri boy, when others his age are already identified as threats by armed and paramilitary forces, and a CRPF jawan haunted by guilt and aching for his eight-month-old daughter he’s yet to hold for the first time, Aijaz Khan tackles the anxieties and grief of living under military occupation and the personal demons that those who brutalise others live with.

The Hindu-right uses the deaths of defense personnel to gain political mileage, reaping votes from the dead bodies of soldiers. Neither they nor their hyper-nationalist supporters care for the conditions those soldiers live in, even when they take to social media to proclaim their loyalty to them. They don’t care for the mental health problems they suffer from during and after their time in service. They don’t care that a toxic masculinity and violent patriotism runs corrosively through these forces. They also don’t care when Kashmiris are disappeared, detainted, maimed, raped, tortured, imprisoned and killed by them. The celebration of the Modi government’s decision to scrap Article 370 makes one thing increasingly clear: India wants Kashmiri lands without the Kashmiris.

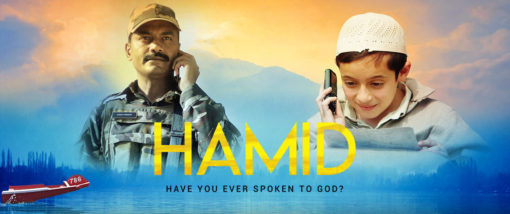

Film Still from Hamid| Courtesy Netflix

Film Still from Hamid| Courtesy Netflix

It’s now becoming harder and harder to hope that films like Hamid, No Fathers in Kashmir (2019), Half Widow (2017) or even The Dear Disappeared (2018) — a film about the enforced disappearance of Fayaz Ahmad Beighin in 1990, (a collaborative project between APDP, the University of Warwick’s Social Sciences ESRC Impact Acceleration Account and Dr Goldie Osuri) — will push Indians and the international community to take a stand. But the films provide us another platform from which to speak. Filmmakers like Khan offer writers and those of us who believe in cultural resistance, a way into the conversation alongside civil liberties activists, human rights groups and a small number of political figures. Hamid has won the awards for Best Urdu Film and Best Child Actor (Talha Arshad Reshi) at the 66th National Film Awards this year. The announcement came on August 9th, but this joy is imperfect. Aijaz Khan can’t even contact Talha’s family in Kasmir to tell them about their son’s accomplishment.

In the film as Hamid’s mother goes to one of the silent marches held by families of the disappeared and the CRPF clash with separatists in another part of town, he makes one last call to Abhay. Abhay’s small efforts to quietly help the family has been noticed. Also a fellow jawan, his friend, has died the previous night. He is warned by a superior officer, “You’re a solider. Stick to being one. Don’t do politics”. In their final phone conversation Abhay tells Hamid, “I’m not Allah. I’m a CRPF jawan. I work for the Government of India”. “You’re the enemy?!” Hamid screams. “Yes and you mine.” Abhay answers.

Film Still from Hamid| Courtesy Netflix

Film Still from Hamid| Courtesy Netflix

Torture, Detention and Disappearances

As of 2015, the number of disappearances since 1989 stands at 8000+ as reported by The International Peoples’ Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Indian-Administered Kashmir (IPTK) and APDP. They calculate 70,000+ deaths, 6000+ unmarked and mass graves and countless cases of torture and sexual violence. The joint Torture Report put together by APDP and JKCCS traces the connection between dense military occupation, detentions, disappearances and custodial deaths. It notes that in 2018 legal and illegal occupation by armed forces in J&K together amounted to 40,000 hectares (400 sq. km). “Armed forces personnel are officially or unofficially empowered to arrest, detain, question and search, damage and destroy civilian persons and property with no accountability. Detention (both unrecorded and lawfully recorded under special security laws, such as Public Safety Act, 1978) as an instrument of intelligence gathering is a central component of policing and counter-insurgency” it reads. They further note that “along with police stations and sub-jails, specialised custodial locations in almost every military camp or police station, such as ‘joint interrogation centres’, and clandestine interrogation facilities are sites of torture.”

Protests: Images from the APDP Archives

Protests: Images from the APDP Archives

The Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) wrote in 2005: “The phenomenon of disappearances appears to be one of the principal methods adopted by the state to suppress movements. The state and its agents, after taking a person into custody, do not follow any of the measures for checks and balance imposed on the power to do so. Reasons for arrest are not disclosed; no production before a magistrate takes place; the place of detention is not disclosed to relatives or friends; there is no access to a lawyer; presumption of innocence is thrown to the wind; and there is no protection against torture and abuse. Disappearances or enforced disappearances have emerged to describe this strategy or method adopted by the state”.

Protests: Images from the APDP Archives

Protests: Images from the APDP Archives

Given such grave human rights violations, the abrogation of Article 370 and the method in which it was done leaves little doubt that the situation is only set to worsen. It is shattering to know that the manner in which this imposition was made on the people of Jammu & Kashmir and the utter disregard for democratic procedure is being met with celebrations, not fear.

Pilgrims, tourists and outstation students were removed, a flimsy excuse of “intelligence on security threats” was given, a total communications blackout and a strict curfew continue to be enforced. Senior political leaders have been arrested without any grounds. An additional 46,000 paramilitary troops were deployed in the region as New Delhi decided the future of J&K without the consent of its people.

Protests are being organised across the country and in cities in other parts of the world such as in New York and Berlin. The United Nations has expressed concern that the move will serve to “exacerbate the human rights situation in the region”. Activists are scrambling to help Kashmiri students living elsewhere return home and to rally support for challenging the Government’s move. It is critical that all those who care for human rights and democracy don’t stand mutely on the side-lines.

Last night the Prime Minister addressed the nation. He waxed eloquent about all the “benefits” J&K stood to gain following the abrogation of Article 370 even while the communications blackout continues in the state. The people of J&K continue to be left in the dark. He said that he respects the critics, but they must “put India first”. No. The answer to that is as Eli Wiesel, a survivor of the Holocaust wrote, “We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted … that place must – at that moment – become the centre of the universe.”

Read More:

A History of Article 370

Can SC Strike Down the Presidential Order on Kashmir?

Bhayanakam: Unfortunate Sons