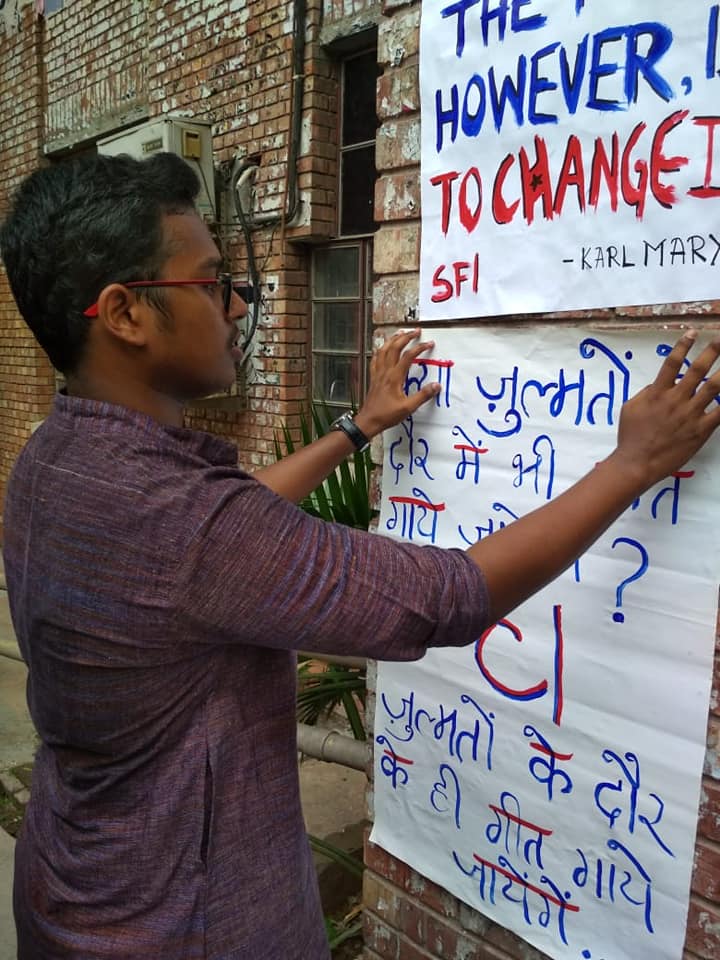

On a hot and humid afternoon in New Delhi, more than a hundred students of the famed Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) were busy making and pasting posters across its campus walls in protest. When asked, “We are fighting to preserve the graffiti culture of the university,” said one of the protesters. Since graffiti, as art and medium, leads a double existence – material and contextual – it is important that we not just look at the content of the posters, but also the present situation on campus that led them to this particular protest.

The Jawaharlal Nehru University is currently facing an attack that is novel in its own recent history of violent repression by the authoritarian and tyrannical university administration. On July 10, the student community received a circular from the administration, this time signed by the “Director of Swachh (Clean) JNU”, which informed that they would soon remove everything that “defaced” or “interfered with the beauty” of the public property on campus. In the following days, the administration began forcefully removing posters from across the campus. The removal of graffiti is only the latest in a long string of repressive measures that the administration has taken to curb campus democracy and to alter the general character of JNU’s campus space. This includes tampering with the progressive admission policy, shutting down all-night dhabas, attempts at introduction of hostel curfews, compulsory attendance amongst other things.

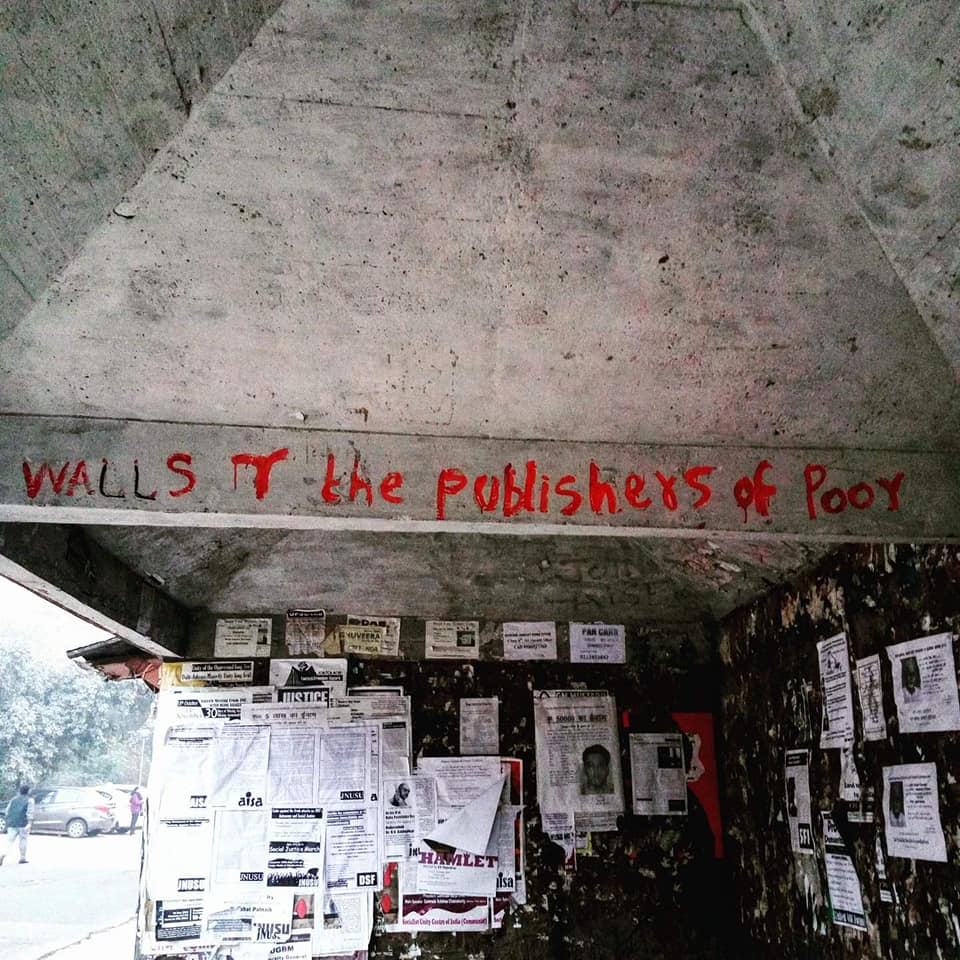

Walls are the Publishers of the Poor

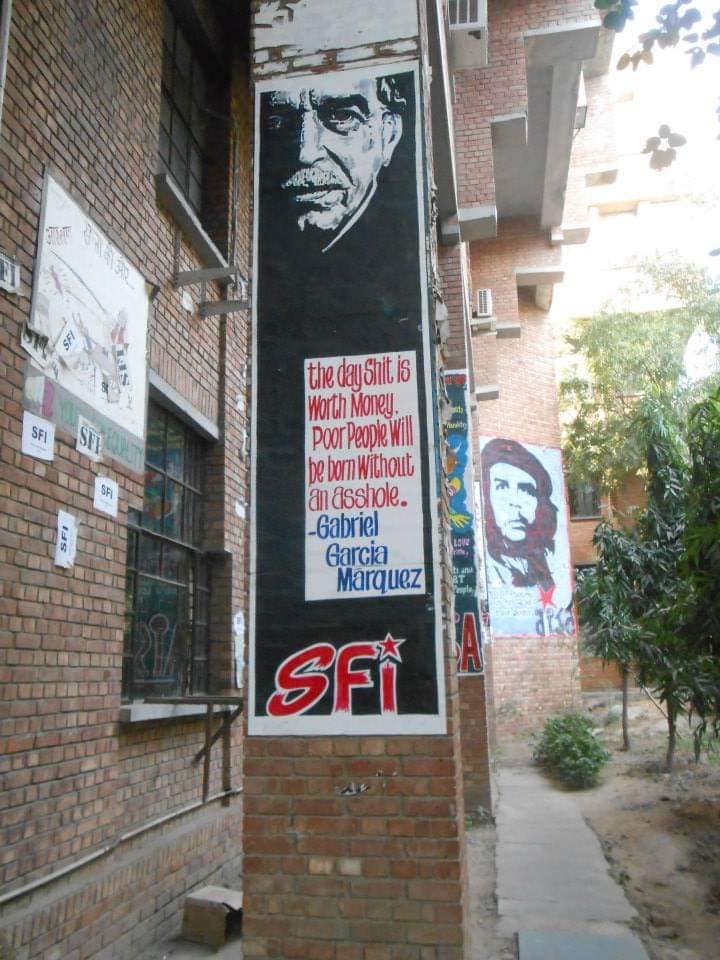

JNU’s long history of student politics is symbolised by the radical and poly-vocal graffiti present across its campus — on hostel walls, academic buildings, canteens, libraries. Posters by the many students’ organisations that function within the university, speak of the countless people’s movements from around the world. A crucial part of the university’s political and pedagogic discourse since years, the graffiti also deal with the contemporary, like the culture of the moment, price rise, the Telangana movement, the rise of the Right, Kashmir and Palestine, besides commemorating past struggles. They also exist as an archive to JNU’s own past struggles.

Every year, the summer preceding the students’ union elections, students of various organisations indulge in intense research for art that best suit their principles, followed by mass graffiti making and plastering on the walls. A form of art widely celebrated as an “embodied engagement” with one’s environment, graffiti is considered a crucial marker of active political participation. As an annual activity therefore, the walls of this radical space are covered with new graffiti, concurrent to the time’s socio-political developments. Naturally, the campus carries graffiti from organisations of various hues, indicating the “space” this university once provided for the coexistence of contending ideas.

If it is an excerpt from the writings of Eduardo Galeano in the canteen beside the Students’ Union Office, it could be anti-imperialist heroes and oft mis-represented historical figures like Tipu Sultan featured elsewhere; if it is the weathered faces of the global Left like Marx, Stalin, Lenin and Mao on a library wall, struggles from different corners of the country — from Manipuri anti-AFSPA activist Irom Sharmila, Odisha’s struggle against POSCO and Adivasi leader Soni Sori — chronicled someplace else. There’s Gramsci, Che Guevara and Captain Lakshmi, along with Rosa Luxembourg, Bob Marley and Muhammad Ali.

It is on all of this that the administration has now thundered down with its recent circular – and it speaks of a one-sided narrative, ie. the need for a “clean campus”, that the authoritarian administration longs to impose on the student community. This highly politicised campus’ recent history therefore, is also a history of surveillance, stifling of dissent and a general control over students’ political expression. Union member Kriti Roy exclaims that the scraping down of graffiti is just one of the myriad ways in which the administration intends to shut down all spaces of political expression on campus and feels that the “Swachh” narrative is just a mask to their real intention.

Why Graffiti

It was Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan who argued that the “medium is the message” in his 60s work on the importance of the nature of a medium. What is it about a couple of posters that irks the administration of the university? An urban cultural phenomenon, graffiti uses forums that are odd: it transgresses and looks over the basic utility of everyday objects, like walls, to speak the artist’s mind. This could be what makes this quotidian art an inherently subversive one, for it has the potential to challenge singular narratives and dominant perspectives about what space is and how it should be used. Moreover, the administration’s circular forbidding students’ political expression and their subsequent scraping down of the graffiti on the wall makes one wonder about the ownership of public space, in this case, the campus space. If the several different kinds of graffiti represent the labyrinth of ideologies on campus and their contending claims to space, the administration’s circular aims to override, dominate over and silence the voices by banning anything that seeks to express them. It seeks to silence the alternative ways graffiti offers to see the world around us.

Sociologist Henri Lefebvre in his elaborate study about the “Right to the City” explores the concept of ownership of the city. For Lefebvre, space isn’t an abstract void, but a socially constructed terrain where contending ideas and practices create varied sets of meanings. It, therefore, is also subject to conflicts of ownership, often dominated by those with power. Explored by sociologists in Lefebvrian terms, graffiti seems to reassert the inhabitant’s claim to the space they occupy, by the constant voicing of their desires through the “familiar” and “everyday”.

It is this potential of graffiti to offer multiple ways of seeing, that autocracy and single narratives detest. JNU isn’t alone. Graffiti as a medium itself is met with contending opinions, and more often than not is criminalised. “Unauthorised art” will soon be forbidden and painted over at Prague’s Lennon Wall, that has long remained a symbol of peace and resistance. The widely discussed graffiti on England’s Kendal bridge, which called out to “Declare Climate Change an Emergency”, will soon be removed. On the other hand, at the centre of Sudan’s recent anti-government protests were a couple of artists and a spring of graffiti art that appeared at various corners of the country. During the first Intifada in Gaza (1987-93), graffiti served as the sole medium of information and art for disenfranchised Palestinians, in the absence of any alternative media.

Graffiti continues to thrive as a form of subversive art, of the ordinary, in various parts of the world. JNU’s latest protest to save their campus graffiti also seems to attest to the fact. A small poster held up by one of the student activists at the protest contained an oft repeated line, widely popular on campus these days, that “Fascism Fears Art”, a reminder, yet again, of the kind of times we live in.