“ये हिटलर के साथी,

जनाजों के बाराती,

पूछते नहीं इन्सां को कौन है तू,

पूछते हैं धर्म और जाति।”

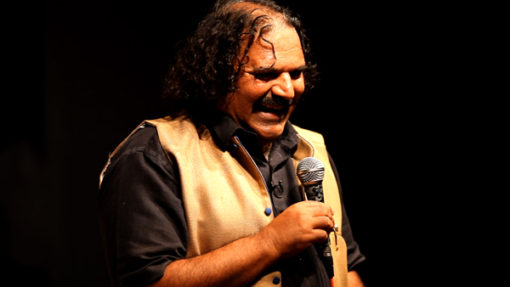

Lokshahir Sambhaji Bhagat needs no introduction. His songs, which challenge brahmanical supremacy and caste discrimination through the use of humour and sarcasm, are a powerful voice of dissent that believes in the upliftment of the broader masses. Bhagat still performs in slums and squatter settlements because he firmly believes that only the awareness and uprising of the downtrodden can truly bring structural change.

On June 8, 2019, a group of culture enthusiasts gathered at the Seagull Space to listen to Sambhaji Bhagat talk about his life–in protest and song. Apologising right in the beginning for his “not too great” Hindi, Bhagat talked about his life, music, and how cultural politics is the only way to bring about structural change in society.

Bhagat received no formal training in music, but was always drawn towards it. He even remembers his childhood through songs–perhaps this is why Bhagat chose music as his medium to voice dissent and challenge the establishment. He uses the traditional form of lokshahiri to espouse social and political ideas that seek to shake-up the status quo.

Democraticisation of music

Bhagat recalled the period from 1940s-70s as a phase of democraticisation of music. With the advent of radio, music was no longer restricted to the rich households but made its way into the lowest strata of society. Everyone was listening to music and enjoying it. This was music coming out of the Bollywood, and was not intended for any specific section of society. Interested in music as Bhagat was, he started talking to people, trying to find out what it was which drewpeople towards Bollywood music. When he asked his father, his father replied , “Maloom nahi beta, lekin apna sa lagta hai,” recalls Bhagat.

Bhagat also held cultural surveys in several villages of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and so on to find out about the traditional forms of music prevalent in the areas.

Like most of us, the teenage writer in Bhagat thought that no one could write better than him. But when he showed his work to his mother and she couldn’t relate to it, he realised that “apni maa ko jo samajhta nahi, wo nahi likhna chahiye (one should not write what one’s mother cannot relate to).” This was crucial because Bhagat realised that while music had made its way to almost every household, the content of that music neither addressed any socio-political issue nor did it have the potential to bring about change.

Sambhaji Bhagat has come a long way since. His music has enabled people to understand the complexities of oppression in a simplified manner and this journey hasn’t been an easy one.

Earned Democracy is Valued Democracy

Though Bhagat was initiated to radical politics when he moved to Mumbai, yet the understanding of oppression and resistance came to him quite early on. Born into a dalit family of landless labourers, Bhagat grew up in the Satara district of Maharashtra. His village Mahu had separate wells for upper castes and lower castes. “Though I learnt the reality, I tried to subvert it,” Bhagat recalled, “I would often fill my container from the Maratha’s well”.

“Those who have been denied democracy, understand its significance and they are hungry for it. He continued, “hum aasaani se progressive ho gaye hain (We have taken being progressive for granted).”

Here was a man, sitting in a room full of people who were, in all probability, aware of this discrimination and oppression, aware of the need for resistance, aware of the need of progressive politics. He was talking about his own struggle and the struggle of thousands of people who are paying the price of being born into a certain religion, caste or gender; and he was not afraid to hold a mirror for us to reflect on our reality: we have indeed taken being progressive for granted.

Bhagat’s songs are peppered with no-holds-barred-anti-establishment lyrics. He not only talks about right wing politics but also about the crisis of the Ambedkarite movement. “The so called Ambedkarites who claim to do anything for Baba Saheb, who are ready to give their lives for Ambedkar, know nothing about him or his teachings. When I ask these people to tell me what Ambedkarism is, they have no substantial answers, they know nothing,” Bhagat said.

Cultural Fascism and the need to build an alternative narrative

Bhagat also talked about his 2012 play Shivaji Underground. Recalling the 1992 riots post the Babri masjid demolition, he said, “Babri masjid demolition was the beginning of the demolition of the country’s democracy.” He recounts one evening, post the demolition. Riots had begun, he was on his way back home, when he saw a group of men crushing another man’s head with a stone not more than 10 feet away. They had banners of Shivaji in their hands. Sambhaji felt nauseous at the site of such inhumanity. He somehow made it home safely, but he was barely okay.

He spent five years after this incident studying Shivaji, because he felt that the “Shivaji” portrayed by the right wing was a “destructed” Shivaji. This is the kind of cultural fascism the right-wing engages with – erasing and re-writing histories.

Bhagat firmly believes that there’s no point in interfering with what the right-wing is doing. The real solution lies in creating an alternative that can stand as a strong counter-narrative. Shivaji Underground is perhaps an attempt at that. Because Sambhaji’s Shivaji is different from the mass imagination of Shivaji, it was difficult to find someone willing to hold a performance. Bhagat barely had enough money for five performances and thought that would be the life span of Shivaji Underground.

Today, Shivaji Underground has not only been performed over 750 times, the play is also critically acclaimed and Bhagat has received the Marathi International Film and Theatre award for music design. “If Shiv Sena’s Shivaji is being watched by one lakh people, there are 30-35,000 people who come to watch Shivaji Underground too, and that matters” Bhagat said.

But cultural hegemony is strong and one play can only do as much. “It would be wrong for me to say that my work alone can help the suppressed. Art plays an important role, but along with it, we need a people’s movement.”

Taking the Indian Constitution to the people

Only a mass movement with mass mobilisation can bring about change and that is what Bhagat is trying to do. “We are trying to make people aware, so that we can together strive for change,” he said.

Bhagat and his team visit slum settlements in Mumbai, go from door to door, and read the Indian constitution. “First we gathered a group of 70-80 kids—through street theatre, songs etc. These kids cover up to five houses daily. They talk to the elderly and tell them that our Constitution is an important text and we need to promote and propagate it. Then they gather all the family members in a room and read the preamble of the Indian Constitution,” he explained.

Discrimination is deeply entrenched in the minds of so many people of our “democratic” nation. We are becoming witnesses to numerous such instances everyday and now is the time, more than ever, to look back at our Constitution, to learn democratic values, to fight for democracy.

That evening when Sambhaji’s voice roared as he sang of women’s struggles and caste struggles, I was certain that if one mind becomes democratic, it can turn the consciousness of many people democratic. As I was leaving, Sambhaji’s words resonated in my mind, “Our country can only change with cultural politics and we need a people’s movement to make that happen.”

Read more:

हिटलर के साथी

Cultural Politics Needed for Structural Change in Society: Sambhaji Bhagat