Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

“Nobodies do not have gods; they are gods.”

There are gods who spring to life from the blood of the oppressed. The dead, unjustly murdered come back as avenging guardians, primal in their sense of justice. This is often the lineage of “folk” gods otherised by institutionalised Vedic Hinduism. A Hinduism that is jealously guarded by the upper-caste. Director and writer Leena Manimekalai’s upcoming film, Maadathy – An Unfairy Tale tells the story of a mother goddess of the same name. But her story is also the story of the Puthirai Vannar women. Puthira Vannars are a dalit sub-caste who are considered the lowest in the caste hierarchy. They are supposed to wash the clothes of other dalits, the menstruating and the deceased: a “slave caste” says Leena. They are told to remain out of sight because even to see them would pollute the “pure”.

The director tells the story of the women made doubly invisible by caste and patriarchy through the life of one adolescent girl fighting for visibility. Speaking to the Indian Cultural Forum, Leena Manimekalai says, “The girl becomes immortalised and these folklore stories are very much part of our culture. I grew up hearing them and I felt that those stories tell my real history. Not the ones I read in textbooks. The history of nobodies is in the folklore. I found my hero from one of those stories.” Dalit oppression bans them from entering temples, from seeking the protection of a deity. “What other than stories and oral histories does the subaltern have for their solace and hope? They are nobodies. That’s my tagline; nobodies do not have gods; they are gods” she adds.

This powerful and compelling story is now facing possible censorship. The Regional Officer, Chennai of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has denied an Adults Only (A) certificate for the film that she had applied for, unless Leena makes the cuts suggested by them. Her concern for sexually exploited adolescent women from an oppressed community has been deemed “immoral”. The film is being refused certification on the grounds of “Religious Contempt, Nudity, Strong Language and Portrayal of a Minor Girl in Infatuation” Leena tells us. The film has been made with community participation with regard to the cast and the writing. “I use the language spoken by the very people whose story I am trying to tell. We don’t censor language that has rape culture ingrained in it, in our everyday lives, right? Then why sanitize it in films? CBFC has no business interfering in our creative calls. If Bandit Queen can have nudity, why not my film? Nudity is primal and when I deal with a story that expresses primal instincts, I have to portray that.”

Legal Complexities

The Cinematography Act, 1952 provides some of the guidelines for the CBFC’s functions. The Act also provides the applicant (the filmmaker) the chance to appeal against refusal of certification without modifications or the granting of a certificate other than the applicant’s preferred choice. The appeals are brought to a Tribunal hearing in an office specified by the Central Government. Leena will soon be appearing before such a Tribunal to appeal the refusal of an (A) certificate without cuts to Maadathy. The film director reminds us that the CBFC ought to be functioning primarily as a certification board, and not as a censor board.

It is a tough fight, especially for independent filmmakers who have more to lose than studios with big budgets. The principles for guidance such as the following, for certifying films are provided under the Act:

“A film shall not be certified for public exhibition if, in the opinion of the authority competent to grant the certificate, the film or any part of it is against the interests of [the sovereignty and integrity of India] the security of the State,friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite the commission of any offence.”

The Act appears to have gone through many amendments over the years, which seem to shift the responsibility of the board towards certification rather than censorship. Yet, the official CBFC website offers links to the 1952 Act and the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983 as references for applicants. It also provides broad guidelines for certification in a separate page on the website. The following is one such example:

“Scenes –

showing involvement of children in violence as victims or perpetrators or as forced witnesses to violence, or showing children as being subjected to any form of child abuse.”

All of this leads then to the question of why governments and/or bureaucrats need to be provided with the means to interpret films, especially those dealing with crucial social justice issues with heavy handedness? Take more such examples:

“The Board of Film Certification shall also ensure that the film

i. Is judged in its entirety from the point of view of its overall impact; and

ii. Is examined in the light of the period depicted in the films and the contemporary standards of the country and the people to which the film relates provided that the film does not deprave the morality of the audience.”

Or

“Human sensibilities are not offended by vulgarity, obscenity or depravity”

ICF spoke to Indira Unninayar, the lawyer who will represent Leena at the Tribunal hearing, to ask the many pressing questions regarding censorship and free expression. She pointed out that world over, film censoring is becoming obsolete as countries become more progressive and liberal. “The Act certainly empowers the CBFC to evaluate a film based on certain guidelines. The guidelines have some normative value which the government has placed as a benchmark for the CBFC to evaluate a film. But the purpose is not to be sitting there with the intention to chop and cut and say that I have the power to chop this thing until you make the cuts to the film.”

We also discussed the legal value of words such as “morality” “obscenity” “decency” “public order” and “religious contempt”. Morality, obscenity and decency seem to be philosophical problems. This language in these guidelines and Acts peg the fate of films on personal and subjective values. On what grounds then, can the law appeal? “Yes, their subjective nature is the reason that films run into problems. They are left to the values of the authorities” she agreed. “But that is why the Supreme Court has laid down the term “reasonable”. It should be according to the values of a “reasonable person and not a weak-willed person” which is also subjective, of course.” She explained further that there is second factor that is also taken into consideration. “Take obscenity for example, if there is a social evil – and the point of showing that is to curb that evil, the artist’s right to expression will prevail. Ultimately, yes it rests on somebody’s value system.”

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Referring to freedom of speech as a constitutional right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a), she explained that it is subject to “reasonable restriction” under Article 19(2) of the Constitution. These are the issues that Maadathy will have to contend with at the Tribunal hearing.

Discussing Leena’s case, the lawyer continued “The Regional Officer has said that some aspects in the film are beyond credibility. It is impossible for a 15-year-old to have any infatuations, in her view.” Maadathy appears to deal with both budding sexuality in an adolescent and sexual violence. The first completely natural, the second predatorial. Asked if the portrayal of minors as having sexual desires violates any child protection laws, Indira confirmed that it doesn’t. She was also quick to point out that this is a person approaching adult-hood and not a small child.

“Similarly the RO has also refuted the title denying the possibility of how subaltern gods are believed to come to life. The fact of the matter is, people in her position aren’t even aware of such belief-systems. These are things that we will have to challenge and explain at the hearing. You also have to give examples of other films that have been passed where the courts have judged that certain scenes are shown with regard to a certain religious faith and not to titulate.” She further elaborated that they will have to refer to instances when the Supreme Court has ruled that social realties do need to be depicted in order to curb social ills. The answer isn’t a cover-up and pretending that it doesn’t exist. Depicting this is entirely up to the artist.

“It’s unfortunate that many of the authorities, especially ROs aren’t even aware of various religious rituals. When you give them the examples of court-rulings, they say that, that applies to the courts, not us. You have to even lay it out for them, that it is the law of the land and everybody is bound by it.” Unninayar also added.

“I was asked to remove texts that mentions that our folk gods have a backstory of injustice. I was accused of religious contempt. I was questioned on how I could show a minor girl in infatuation” says Leena. “They demanded that I clean the language used in the film.”

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

Image Courtesy : Leena Manimekalai

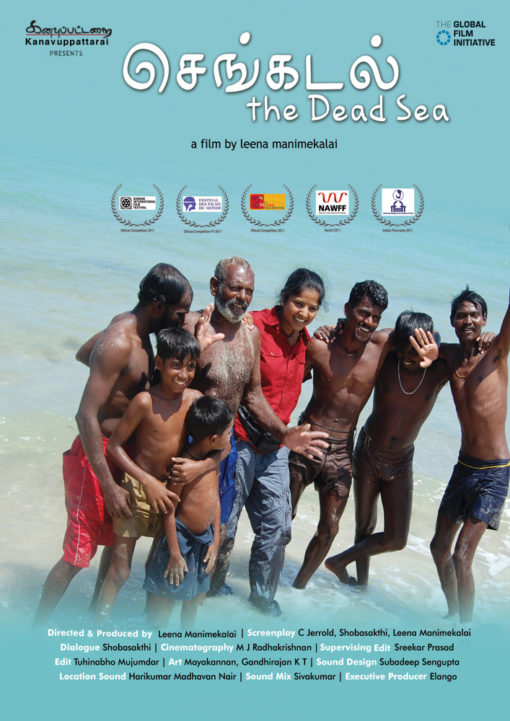

This is not the first time that Leena Manimekalai’s work has been subject to censorship and backlash. Her debut film Sengadal (The Dead Sea) dealt with the lives of fisherfolk and refugees in the Indo-Sri Lankan border shores. The CBFC refused to pass it fearing it would impact diplomatic relations between India and Sri Lanka. Like Maadathy the film was made with community participation. It is their stories that Leena wanted heard. It was cleared after the Tribunal’s intervention. Indira Unninayar represented her in that case too. She has also represented Anand Pathwardhan when his film faced similar censorship. “Why do they make us go to courts all the time, spend our money, energy and resources to get their senseless orders quashed and get reminded that their job is to certify and not censor?” asks Leena.

White Van Stories, her documentary on enforced civil disappearances in Sri Lanka during the war, has been screened in other parts of the world. But not in Tamil Nadu, allegedly because the Tamil Nationalists branded her a traitor for her criticism of the Liberation Tigers of Elam (LTTTE).

The Tribunal will hear Leena Manimekalai’s appeal in the next few weeks. The Indian Cultural Forum will follow up on the verdict.The stories in Maadathy need to be heard. Stories of “folk” gods are stories of dalit and adivasi assertion. Institutionalised Hinduism has made attempts to Sanskritise these gods. Those attempts cannot be viewed as “acceptance”. Rather they are a deliberate move to reinforce caste hierarchy through homogenisation. So, why shouldn’t the gods tell their own stories?

Read More:

Witch-hunting Writers: From Turkey to India

Aabhaasam: Democracy Travels at Night

The Exclusions in the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) 2018: Some Thoughts