Over the recent past, Mamata Banerjee, the present Chief Minister of West Bengal, has made persistent allegations that the “outsiders” or “bohiragato” – people who come/came to stay in Bengal from other states — are to be blamed for the current crisis of West Bengal, which includes the assault on the two doctors of NRS College and hospital.

Banerjee, however, avoids defining what precisely she means by the word “outsider” or bohiragato. Let us take a closer look. The grocer around the corner from where I get my monthly grocery is from Bihar, but he has lived in Calcutta for almost all of his 27 years and knows how to read, write and speak Bengali just as I do. Is he an “outsider”? The dhobi who sets up his ironing table right below my balcony is from UP and has a Bengali wife. His father brought him here when he was seven years old and he learnt Bengali in school. He considers himself a Bengali by adoption and his kids speak in both Hindi and Bengali. Should we call him an “outsider”? My driver, born, bred and educated in Calcutta though his family originally came from Rajasthan, speaks Bengali so fluently that you would not know what his mother tongue is unless he tells you. His wife is even better at the language. The hand pulled rickshaws that dot the city of Calcutta do not generally have Bengali as their mother tongue. But they have integrated into a mainstream which has evolved a much wider meaning today than the conventional one we associated it with.

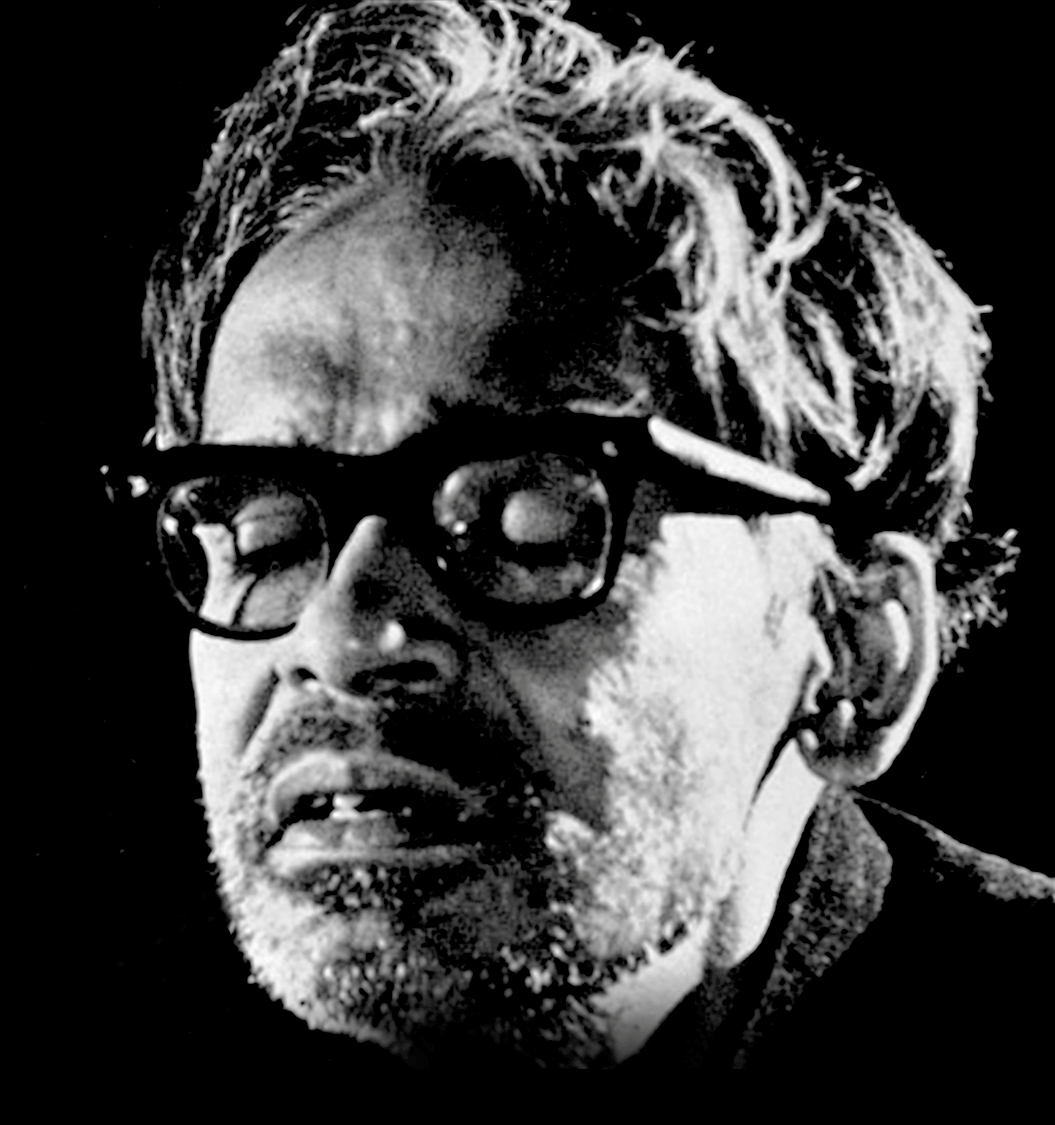

“Refugee?” filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak asks again and again in his films. “Who is not a refugee?” A documentary on Ritwik Ghatak entitled Name of a River (2003) by Anup Singh set out to find answers to the question Ghatak posed in and through his films, in myriad ways – is mostly angry, often restless, reflecting the state of his schizophrenic mind, forever vacillating between his roots, Bangladesh, and the city that was the base of his uprooted identity, Calcutta. But Ghatak purged his pain through his films, irrigated with blood as they were, and did not go back except to shoot the last two films when he was quite sick. He died soon after. Would he be called an “outsider” or a “bohiragato” by Mamata Banerjee?

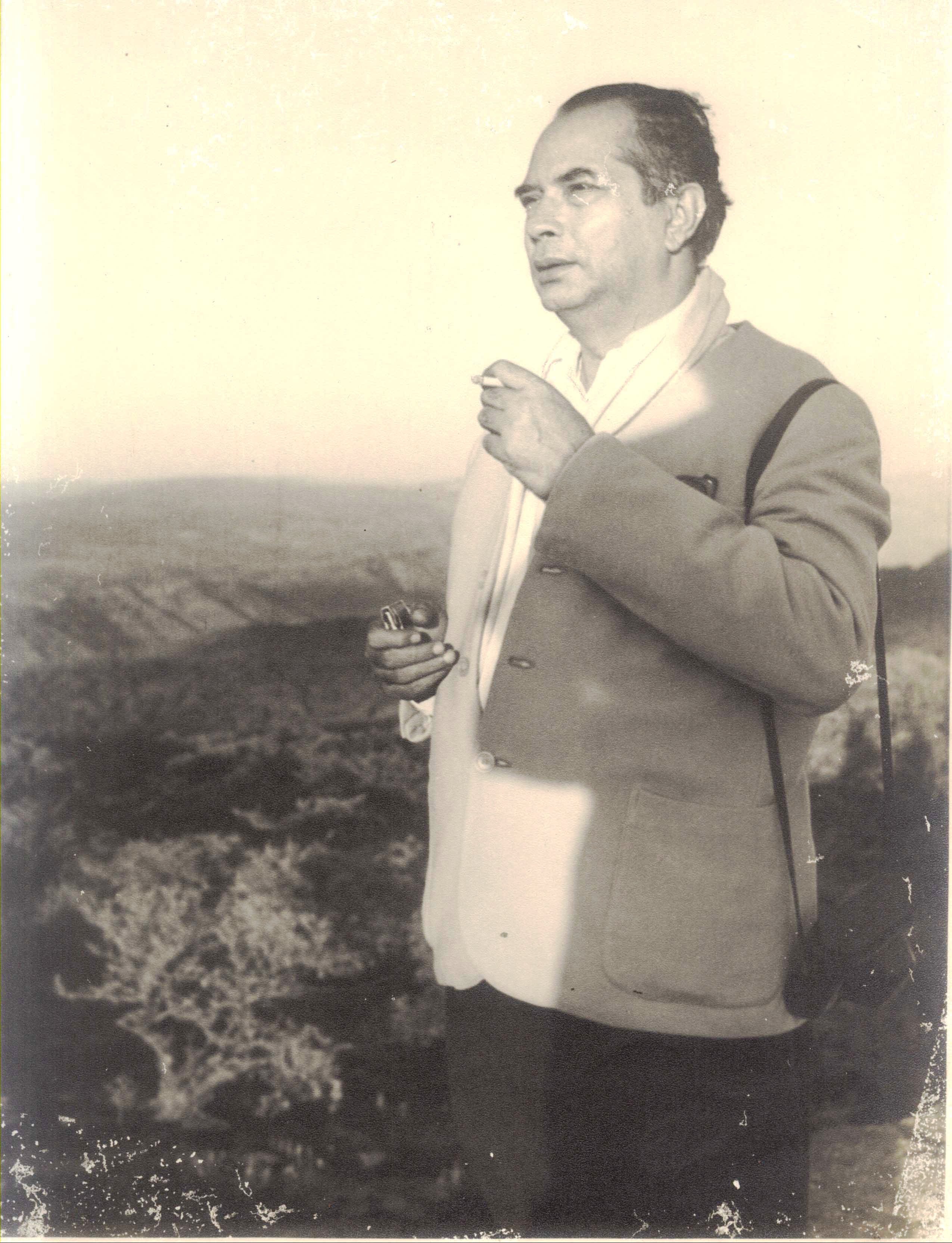

Filmmaker Mrinal Sen who was born in Faridpur, now in Bangladesh, arrived in Calcutta when he was 17 and continued to live here for around nine decades till his passing away early this year. “As soon as I came to the big city, I was seized by a kind of fear. I confronted a crowd, a huge crowd. I felt lost. I felt I was standing alone in the crowd – anonymous, self-absorbed, indifferent swarms of crowd, even menacing and monstrous. Loved by my parents and liked by my small-town teachers, I was now reduced to anonymity, suffering acutely from a depressed sense of emptiness. Till things proved different,” he once said. This predicament of a small-town boy being suddenly thrust into an ‘alien’ world is not uncommon, “unless the victim shows traces of uncommon features in himself. I was an average boy of average intelligence, and that was why I was affected so easily.”

In retrospect, coming from a man who went on to make nearly 30 films between 1956 and 2002, this underscores how little Mrinal-da understood his own potential. As a teenager thrust into a new world, he found himself grappling with a new cultural and geographical context where the only thing in common between the culture he had left behind and the culture he had now stepped into was the language – Bengali. Many of these films have won international acclaim and some created milestones in the history of Indian cinema. How would he be defined today, beyond his death? As an “outsider” who lived in Calcutta for so many years and made nearly 30 films?

Filmmaker Bimal Roy was not a “refugee” in the political understanding of the term as he came to Calcutta much before Partition. The identity of East Pakistan had not been established. He was displaced and as his background reveals, the uprooting from Suapur did not happen of his own will. He was forced to leave by reasons of the extended family of uncles wishing to appropriate his and his brothers’ share of the land and property. The migration to Bombay happened by invitation and no one had a clue, including Bimal Roy himself, that there was a displaced artist who would write himself into the history of Indian cinema forever.

What necessitated Bimal Roy’s migration from Calcutta to Bombay? The collapse of New Theatres, the pressures of World War II on Calcutta, and the advent of Bombay cinema heralded a new phase. His migration to Bombay1 precipitated his understanding of the migration from rural areas to urban centres as one great social phenomenon of independent India. If Bimal Roy intended to make a statement upon his arrival in Bombay, he did it with Do Bigha Zamin and not with his first film which was Maa and which he was invited by Bombay Talkies, then going through financial bad times, to direct and which brought him to Bombay in the first place. He never came back to Calcutta but all his films carried the smells, the aura, the ghosts and the emotions of the Bengali identity even in films where the characters spoke in Hindi. If he were to come to Calcutta today just to make a film, would he be described as an “outsider”?

Suchitra Sen, one of the historic megastars of Bengali cinema, was born in Pabna, originally in the northern parts of undivided Bengal (now in Bangladesh), it was her marriage to Dibanath Sen which brought her to Calcutta and she never went back. She became the first female star in post-Colonial Bengali cinema and her contribution remains unparalleled to this day. Would one dare to label her an “outsider”?

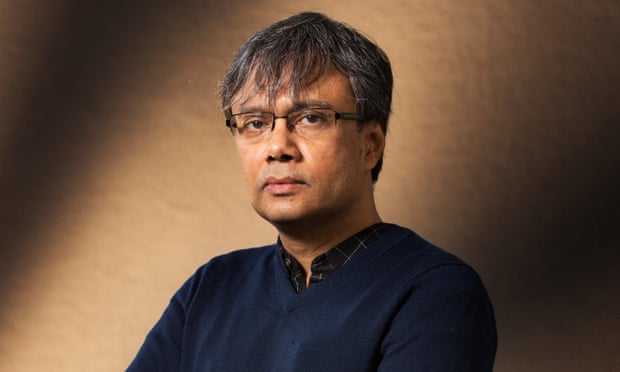

Amit Chaudhuri, famous author, literary critic, scholar and professor was born in Calcutta in 1962. His mother Bijoya Chaudhuri was a very well-known and accomplished musician who had mastered different schools of music such as the compositions of Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Atul Prasad Sen and Hindi bhajans. His mother was his first teacher in music. But the family shifted to Bombay when his father got his posting there and his schooling was in Bombay. He graduated in English literature from University College, London and he completed his doctoral studies at the Balliol College, Oxford. He was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2009. He is a professor of Contemporary Literature at the University of East Anglia. In 2015, Chaudhuri began drawing attention to Kolkata’s architectural legacy and campaigning for its conservation. He has also edited a thick volume of essays on Calcutta. He divides his time and space between Calcutta where he is now settled and the UK where he teaches. We would like to ask whether the CM would consider him an “outsider”?

The word ‘place’, geographically speaking, can be defined as an area or a region which possesses some characteristic in the context of preconceived ideas, local conditions or events. But the term has varied meanings when it comes to literature, films, music, architecture and photography2. More importantly, when a creative person finds himself ‘displaced’ in geographical terms, he does not immigrate as an individual who exists and functions in an emotional, cultural and social vacuum. He brings along with him the baggage of his past into his present, a past that has shaped him into what he infuses into his present that determines, in a manner of speaking, his future and his destiny. This is explained in lucid terms by filmmaker Jahnu Barua when talking about Roy’s films. He writes: “We see in Roy’s films, a transplantation of the ethos of Bengal to Bombay and the Bengali language interpreted in Hindi much after the manner of the migrants from north-west India, particularly Lahore, after the Partition in 1947, who brought their culture and way of life to the cinema of Bombay. Place is “an amalgamation of completely independent and often, conflicting ideas. All great works of art move beyond preconceived notions of geography and frame a comprehensive construct by infusing it with the creator’s individual quirks.”3

One is not considering here the Freudian concept of displacement where displacement is defined as “an unconscious defence mechanism whereby the mind substitutes either a new aim or a new object for goals felt in their original form to be dangerous or unacceptable.”4 One is considering rather, the immigration that an individual must go through when he/she is displaced from his/her place of origin/birth/family. He/she has to begin life all over again in this new physical setting, find out new avenues of earning the basic survival needs of food, clothing and shelter followed by the extended needs of health, education, socialisation, and entertainment. This involves a strong coping mechanism that would help the displaced person to adjust to his/her new surroundings not only in terms of physical coping but more importantly, in terms of emotional and social coping besides the question of adjusting to climatic, language and cultural changes.

In common understanding, the word ‘place’ is also referred to as dwelling or a place where someone has lived for a long time and has imbibed the social and cultural values of that region including creating and functioning within a social network of the neighbourhood. A place can also exist in the mind creating mind-spaces where a world of dreams distanced from reality exists, sustains and perhaps, even enriches and entertains. If the literature which Bimal Roy chose had imaginary places and spaces, then he left a part of him behind in these worlds he transformed from literature to cinema. This is another way in which he channelized his displacement and his feelings of uprootedness if there were any left.

Salman Rushdie believes in the integration of cultures and identities and goes on to denounce the idea of one nation, culture or even home. Living in London, the settings for most of his works is India, where he was born. He refutes the idea of being an exile and accepts both places with their cultures and identities. Do these qualities not enrich a larger and more expansive and progressive society instead of one which closes its doors to “outsiders”?

Writers, painters, sculptors, filmmakers, playwrights have been able to successfully convert the “displaced” identity of a subject into a rich and informed creative discourse which can fill an entire library and museum and gallery of wonderful films, books, paintings, and the like. Intellectuals and creative artists in India and those who may have migrated to Calcutta from elsewhere or migrated from Calcutta to someplace else have demolished preconceived Western and Eurocentric perspectives of place and displacement and “outsider-ness.” They have created, invented and redefined the concept of displacement not only of in terms of personhood but also of a person’s existence in a given place. This can be as ambiguous and ambivalent as it might be uncertain and amoeba-like, grow in every direction in every which way till one fails to pin it down with a definite identity except in an essentially Indian one. The “outsider” is as much an “insider” like the rest of us because life and place-settings, in reality, are not gloomy, dark places where people would not wish to stay or grow roots or both. Interpretations of place and the displaced elevate the possibilities of a lived reality that cuts across time, space and geography though they remain rooted to the culture they were bred in. Do “outsiders” really exist?

Notes:

1. Lal, Vinay: Bimal Roy (1909 – 1966), https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/Culture/Cinema/bimalroy.htm

2. Raj, Neelabh: Beyond Physical Realms, Life and Letters, The Statesman, 8th Day, February 7, 2016, p.3.

3. Ibid, Raj, Neelabh

4. Berne, Eric: A Layman’s Guide to Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis (1976) p. 399

Read More:

The Vidyasagar Legacy: What he stood for and what he was against

Bengali Film Bhobishyoter Bhoot Pulled Off from Theatres Without Explanation