Image Courtesy: ThingLink

Image Courtesy: ThingLink

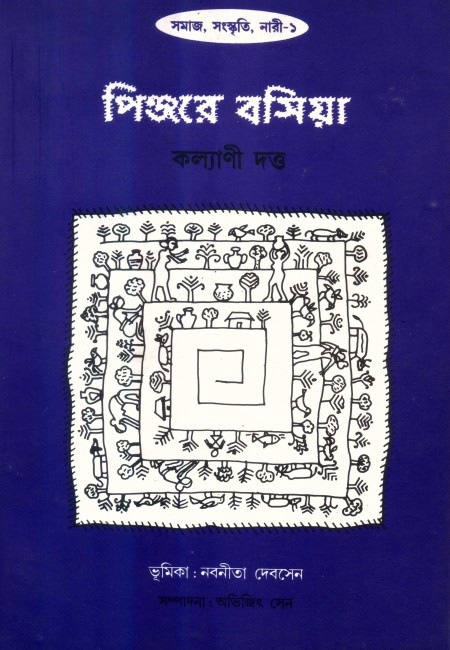

Kalyani Dutta’s Pinjare Boshiya (Sitting in a Cage) uncovers some sad and irreversible truths we need to revisit. Published in 1996 by Stree, a noted feminist publishing house in Kolkata, the book unfolds the tragedies of young women who lived a life of emotional and physical torture simply because they were widows. In most cases, they had been married to men old enough to be their fathers.

Kalyani Dutta taught Sanskrit language and literature at Kolkata’s Basanti Debi College for many years. She was a prolific and distinguished scholar, surrounded by books and students; it helped that was single and lived alone. She was in her seventies when the book was published and one wonders why nobody thought of translating it in different Indian languages. Dutta’s extra-mural researches on the oral history of Bengal also brought forth books, like Thod Bodi Khada and Khada Bori Thod, apart from Baidhabya Kahini (Tales of Widows), most of which are now out of print.

Pinjore Boshiya was first published in 1996 and holds tremendous archival value, as it sheds light on the subject of wives in great Bengali families and what “life in the shadows” meant for them. In her sparklingly informative introduction, Nabaneeta Dev Sen writes that Dutta’s writing underscores the declining importance of oral history in an era of techno-revolution. Her upholding of the woman’s cause does not succumb to the West-influenced brand of feminism that contemporary Indian women seem to be so fond of. In Pinjare Boshiya, Dutta uncovered the fascinating truth of the literary genius of some of her subjects – all of whom were widows of the past century and the turn of the present century. Some turned their culinary books into treatises on history and literature. Not for her only stories drawn from the kitchens and bedrooms of her subjects.

Most of Dutta’s narratives have been drawn from her experiences with women in the family who had been widowed at an early age. Others are based on hearsay, or stories narrated to her by her mother, and colleagues in college, whos had witnessed the condition of a widowed relative being worse than death. Dutta talks, for instance, about one particular far-related aunt who was widowed at 11 and lived to be 95. When she died, her great-grandchildren jokingly remarked that if she could celebrate her 95th birthday surviving on one meal a day all her life, she might as well have gone on to celebrate her 200th birthday had she been given two square meals a day!

Image Courtesy: Stree

Image Courtesy: Stree

The title “Sitting in a cage” metaphorically refers to Bengali Hindu widows who were caged within their homes bythe rigid patriarchal rules defined for them by society. The book traces the period from the passing of the Widow Remarriage Act in 1856 to the 1940s. The accounts/testimonies of the widows described by Dutta are distressing because many women sincerely believed that their sorrows were due to sins of their previous births. Thus, they rigidly/religiously stuck to every single ritual imposed on them without ever raising questions. There are repeated references to their practice of fasting on Ekadashi, which falls on the day after Dashami of every lunar month. On this day, a widow ought to fast the whole day without a drop of water. [The book recounts an incident when during the cholera epidemic if a widow-victim of cholera happened to fall sick on Ekadashi, she had to die because she was not permitted even a drop of water. One pregnant widow, who happened to get labour pains on Ekadashi day, was delivered of a stillborn child the next morning because she could not bear the pains without a drop of water!

There are also instances where widows who had inherited a lot of wealth and land after their husband’s death, learnt how to manage and control that wealth.

In the beginning, they were ensured of a good monthly allowance and good living quarters with the money from their own wealth. However, the money-orders soon stopped. The women were strongly pressurized by their in-laws to go away to Kashi (Benares) to attain salvation so they would not be widowed in their next birth. In the beginning, One such widow who had inherited half the zamindari of her husband’s family was discovered by the author (when the latter went on a pilgrimage to Kashi) in a dharamsala for destitute widows, naked, muttering to herself that she only had two torn sarees and so, preferred to “save” them for the evenings.

“I have no documented proof for my stories,” writes Dutta. “They have been culled from my memories, seen, heard and hearsay. But they are all true and they all have one thing in common: the torture of humanity in the name of widow rituals.”

The chapter on sons with a mother-complex is shocking too. Little-known stories about the wives of great men like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (who triggered the law on widow remarriage), Ramendra Sunder Tribedi, Dr Khetresh Chandra Chattopadhyay, the noted poet Satyendranath Dutta and others are sprinkled generously. The author relates the tragedy of their wives, their oppression at the hands of their in-laws due to the fact that they had socially committed husbands whose commitment to their respective mothers far over-ruled a minimal sense of humanity towards their own wives. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s mother Bhagabati Devi, writes Dutta, would dictate to her daughter-in-law Dinomoyi precisely how she had to chop potatoes for the day’s vegetable dish. When Dinamoyi expressed her wish to learn the three R’s, her husband was happy. But Bhagabati Devi put her foot down and that was the end of Dinomoyi’s dreams to educate herself. Satyen Dutta, a noted poet of his time, had once confessed to his friends that despite being a married man, he led a celibate life because his mother did not allow him to sleep with his wife. Instead of chiding him for such inhuman behaviour, one of his friends bowed to him in reverence, equating him to God! Strangely, none of Dutta’s poetry hints at this tragic side of his life. His poems are odes to love, romance, and the sweet happiness that evolves between a man and a woman.

What stands out is that these real-life stories of women’s oppression are related against the backdrop of aristocratic, wealthy, educated and some very famous Bengali families. A few of the subjects, like Sibmohini Devi, were remarried at the behest of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar himself. But this was possible because she ventured to walk out of her parents’ home with a friendly neighbour’s family. The author is not biased against men. This comes across in her ode to Surendranath Tagore who was extremely supportive of his wife Sagna Devi who took sanyas later in life. This, in spite of his wife’s indifference and her inclination to spiritualism. Dutta celebrates the memory of Sagna’s mother-in-law, Jnanada Sundari Tagore.

One hopes that an English translation of this prized piece would soon be out so that these stories of subjugation and humiliation could highlight the changes that have swept the lives of Indian women today. But the widows of Varanasi and Vrindavan, mostly drawn from Bengal, still live out similar stories through the debris of their lives.

Read More:

25 Years of Kalpana Lajmi’s Rudaali

Remembering Nemai Ghosh, Satyajit Ray’s official photographer since 1969