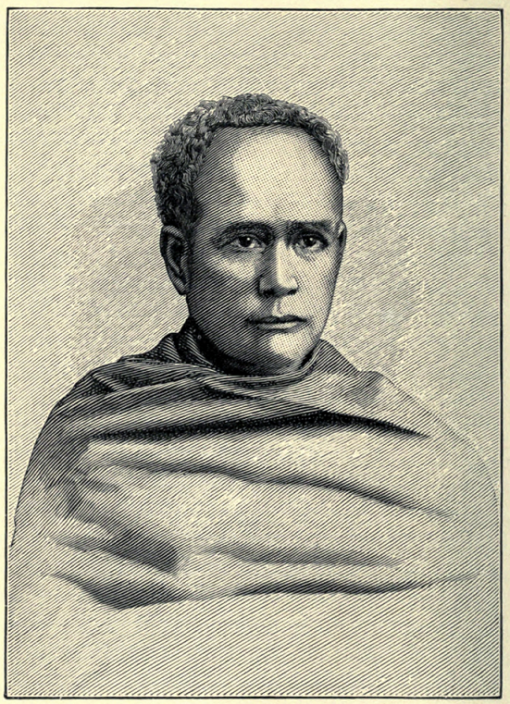

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Once Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was travelling by train in a compartment with some Englishmen. He sat between two of them. One man asked, “Who is this donkey?” The other asked, “Who is this pig?” A third Englishman asked, “Who are you?” Ishwar Chandra coolly replied, “I am a human being sitting between a donkey and a pig.” The two Englishmen felt ashamed of themselves. They felt even more ashamed when they saw a large crowd of people waiting with garlands to receive Ishwar Chandra when he got down from the train. The Englishmen then realised that though Indians might appear simple and unlettered, they were inherently noble and gentle.

Legends such as these about Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar have been a part of Bengal’s public memory since the nineteenth century. Vidyasagar represented an aspiration of an upward mobility even in the face of a colonial government; that even an Indian could command respect even from the British empire.

From infancy, children in Bengali households heard countless times that Vidyasagar learnt the English numerals by following the mile-stones on his way from his native Birsingha village of Midnapore district to Calcutta when he was barely eight years old. Young adults have been told that Vidyasagar passed his law examination despite studying under a streetlight as his parents could not afford gas light at home.

Even as one steps outside of the house, Vidyasagar remains a figure that most Bengalis encounter in their everyday lives. From a street named after him, to a stadium, to a bridge over the Hooghly river, to even holding an annual fair dedicated to the great man’s efforts towards spreading education and increasing social awareness, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar occupies a seat of immense love and reverence amongst the people of the state.

Vidyasagar opened schools and colleges. At a time when scholars like Radhakanta Deb, founder of a conservative Hindu society called, Dharmo Sabha, were promoting English education among the Hindus, Vidyasagar redefined the way the Bengali language was written and taught. Ishwar Chandra Bandopadhyay was a polymath, who had joined the Sanskrit College at the age of nine and studied there for twelve long years, qualifying in Sanskrit Grammar, Literature, Dialectics, Vedanta, Smruti and Astronomy. At the age of 19, he was bestowed with the title of “Vidyasagar”, meaning ocean of learning for his brilliance. He opened schools and colleges and brought about a revolution in the Bengali education system. He advocated for female literacy. Vidyasagar associated himself with Drinkwater Bethune, the Anglo-Indian lawyer who founded an institution for women’s education in Kolkata in 1849. In 1851 the management of the college was entrusted to him.

The desecration of the statue by the BJP goons have compelled for a reminder of the values that the renowned philosopher and social reformer stood for.

The British ruled India in the nineteenth century. In addition to oppression under the imperialistic mission of the British from the outside, the Indian society was infested with social evils from within. To resist these forces of authority and orthodoxy, a cultural, social, intellectual and artistic movement began in Bengal in the nineteenth century and continued till the early twentieth century. Akin to the European Renaissance, this movement was called the Bengal Renaissance. Scholars, writers, religious and social reformers, journalists, patriotic orators and scientists converged together to engineer a transition towards a “modern” India. This “modernity” demanded a reconfiguration of the boundaries between the public and private. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Ram Mohan Roy were pioneers of the Bengal Renaissance which so mightily changed the whole aspect of not only the Bengali life and thought, but also transformed the domestic landscape of the Hindu society forever.

Being a learned scholar of Sanskrit, Vidyasagar had discovered that the ancient Hindu scriptures did not enjoin perpetual widowhood, and in 1855 he startled the Hindu world by his work on the Remarriage of Hindu Widows.

To the Hindu orthodoxy, the body of the Hindu widow was the site for maintenance of caste purity through ritual austerity. Polygamy was practised and young girls were married to men thrice their age, either in the name of tradition or to avoid dowry. Girls became widows soon after marriage, often even before their marriage was consummated. They were subjected to a life of deprivation, humiliation, abuse and ostracisation inside their homes. They were denied the basic rights to bodily integrity: stripped of jewellery, forced to wear only white, and ration their food intake. Apart from these restrictions, the body of the widow also generated anxieties regarding her sexuality.

When an upper caste Hindu male like Vidyasagar called out these violent cultural practices which operated under the garb of “protection” or benevolent tradition, it caused an uproar. While an agitation against the orthodox Hindus, the priests and leaders of religious communities was something expected, Vidyasagar also had to face opposition from the concerns of the nationalists. To these nationalists, who were also learned scholars, the question of women empowerment “was not so much about the specific condition of women ..as it was about the political encounter between a colonial state and the suppressed “tradition” of a conquered people.”( Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and Women”). The passing of a widow remarriage act, seemed to this group, a Western import which had no place in a traditional Indian society.

Yet Ishwar Chandra persevered amid a storm of indignation. Associating himself with the most influential men of the day like Prosonno Kumar Tagore and Ram Gopal Ghosh, he appealed to the British government to declare that the sons of remarried Hindu widows should be considered legitimate heirs. The British government responded; the act was passed in 1856, and some years later Ishwar Chandra’s own son was married to a widow. In the last years of his life, Ishwar Chandra wrote works against Hindu polygamy.

Vidyasagar stood for critical consciousness and the spirit that interrogated everything. Last year, when the BBC Bengali Service asked its listeners about “the greatest Bengalis”, Vidyasagar was part of the list. With a smashed statue of the man in a college named in his honour, in the city of his birth, what kind of legacy are we really left with?

Read More:

“Yarukkaghilum Bhayamaa” – Whom should I fear, asks T M Krishna

Hindutva, Media and Propaganda