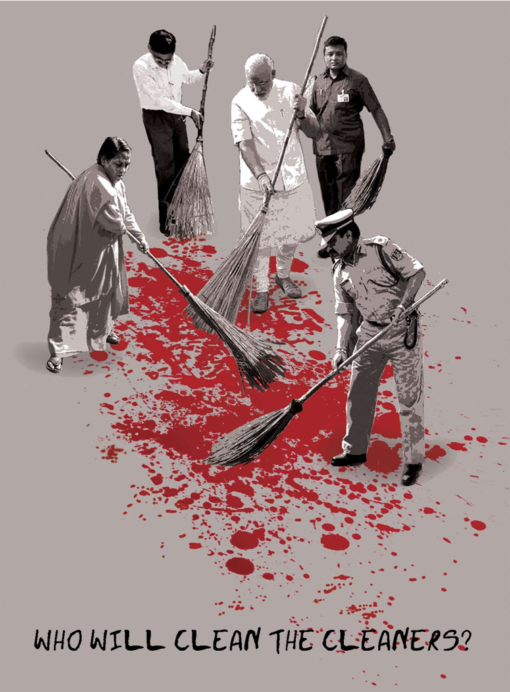

The Swachh Bharat Abhiyan has no meaning while manual scavenging remains a reality. In conversation with Prabir Purkayastha, Bezwada Wilson, leader of the Safai Karmachari Andolan and a Magsaysay Award winner, talks about how the inhuman practice of manual scavenging is forced on the “lower” castes. With the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan’s new aims of building toilets, the already burdened scavengers will get an added job of cleaning the new toilets. Wilson remarks on how the government has no plans to tackle this problem. The lack of technology adaptation in this area will result in a perpetual oppression of this particular caste of people. Under the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavenging and Their Rehabilitation Act, an amendment to the law in 2003 brought the cleaning of septic and sewage tanks under its purview. Section 7 of the law prohibits local authorities or agencies from employing a worker to clean sewers and septic tanks. Despite these provisions, the situation on the ground remains dire, not helped by problems with the collation of data about such work, as when the Delhi government found only 32 manual scavengers in its survey in August 2016.

Prabir Purkayastha (PP): Bezwada Wilson, let’s talk about this problem we seem to have made for ourselves—people dying every year as they clean our sewers and septic tanks. What kind of figures do we have?

Bezwada Wilson (BW): See, we do have figures, but these are from a few towns—nothing exhaustive, more like a sample. After the Supreme Court judgement of March 27, 2014 against manual scavenging, the government was supposed to enumerate the fatalities, collate figures and give Rs 10 lakh as compensation. But when we [the Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA)] began going to the government, to its many departments and ministries, we were surprised that none of them had any data on this, leave alone a consolidated list. We started to compile the data. According to our list there have been 1370 deaths, but this is [a provisional finding] from the two years that we have been working to collect data. It is the number we have given to the ministry, but it is not comprehensive.

PP: Yes, the real figure would be much higher. A lot of these workers would not be permanent employees of municipal corporations or municipalities. Many are contract workers and casual workers who go undocumented.

BW: It’s with the sewage system of the metros that you get workers who are full-time employees of corporations. There are also septic tank cleaners, the majority of whom are contract labour, or workers privately engaged by homeowners. Already, workers on the payroll of municipalities and corporations are not a small number. In Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai, Ahmedabad and so on, there is a large number of permanent employees.

PP: Why do you think people, since it’s not just the government, are so callous about this? Do you think it has to do with the kind of people—the castes and communities—who do this kind of work, and a lack of sensitivity towards them?

BW: The sanitation in our country is caste-based. This is very clear and it is the first thing one must understand. The overwhelming number of these workers are “untouchable”. Given this, everybody—the country, the people—all think that if a scavenger is cleaning up after them, what’s so wrong about that? This is the work they are meant to do. Even our own people—since I belong to the same community—also think: What else can we do? After all, we are born into this caste. We can’t do any other work. Also, it’s very difficult to change professions. This work seems easier to us in that we simply continue to do what we’ve been doing, taking the path of least resistance. So, there are two angles at play. But the government does not think about this, about what’s going on.

PP: Do you think part of the reason we don’t think about it is that this caste viewpoint is built into the people who build the cities— those who develop, plan for cities? After all, sewers and septic tanks in urban areas are a global fact, not peculiar to India, but this problem is uniquely Indian. Is it part of our caste-blindness, that we don’t want to see the problem?

BW: We don’t want to see it, and we don’t care about certain lives in this country. Article 21 says we have the Right to Life, but whose life? Which group, which class, which caste? It is clear that some lives count for more than others. In the public sphere, they always say that all are equal; but some are clearly less equal than others. When such deaths occur, the first impulse is to throw money at the problem and make it go away. So, someone died. What’s the big deal? How many children? How much money is it going to take to settle everything? Nobody will ask: How could this person die? With all our science and technology, why are we making somebody go down into the sewers like this? Another reaction is this: these people went and died, so what can I do about it? Never mind that it’s my septic tank, my sewer line, and I engaged these workers. Even the concept of workers and management responsibility doesn’t apply here. Scavengers are easily available. If they accidentally die while cleaning, that has nothing to do with me. This is why the SKA says, It’s no accident. You are killing us deliberately in the sewer lines and in septic tanks, because you choose not to mechanise the job. You know that we are dying. It is important for us to insist on this point, that you have created the conditions for these deaths. So, don’t come around to show your sympathy when we die, because you are responsible for this, and we want a political solution, now.

PP: It’s a matter of justice, not mercy.

BW: I don’t believe in mercy here, and I also think it is time the government took a stand, a decision on this. They can’t keep throwing it back to society, saying it’s a societal problem. No, caste is not a social problem. It may have emerged as such, but the solution must come from the field of politics.

Read more:

Orijit Sen: Graphic Politrix