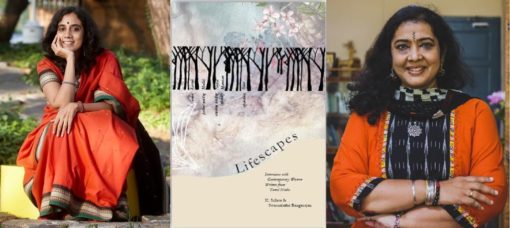

A unique anthology by K Srilata and Swarnalatha Rangarajan, Lifescapes: Interviews with Contemporary Writers from Tamil Nadu, presents the experiences and views of seventeen contemporary Tamil women writers whose works explore the implications of being female in Tamil Nadu today. The writers in this volume draw attention to the inseparability of issues like gender, body politics, caste hegemony, mythopoesis and environmental justice, in their writing. In this conversation with Daniya Rahman of the Indian Cultural Forum, K Srilata and Swarnalatha Ranjarajan talk about Lifescapes, the conflation between women and nature, being women writers and more.

This is the first in a series of posts, leading up to the International Women’s Day, that the Indian Cultural Forum is dedicating to women asserting change in cultural, economic, and socio-political spaces.

Daniya Rahman (DR): What prompted you to go on this journey of creating an anthology of interviews with women writers?

K Srilata (KS) and Swarnalatha Rangarajan (SR): We found that interviews with writers published in anthologies and journals such as the Paris Review are enormously useful as resources, as background to writers whose work we teach. So we wanted to do a similar exercise for our Tamil women writers whom we felt did not get much attention in the Anglophone world. The interviews in Lifescapes offer the non-Tamil reader a glimpse into the diverse contexts that frame contemporary women’s writing from Tamil Nadu. We also made a conscious decision to include a mix of well-known and little-known writers, hoping thereby to tilt the balance a little. These interviews helped us explore a plethora of themes like body politics, the politics of subalternity, environmental concerns and the artistic process.

DR: What is your take on the woman-nature conflation that you have talked about in the introduction to the book?

KS & SR: To understand this conflation we must look at the space of the oikeon—the root word for both “ecology” and “household” which has historically been the space of silence and the subaltern. It is also a fact that in the Global South, whenever the environment is ravaged, women who depend on nature for their livelihood and everyday needs are also affected. Therefore it is not surprising that most of the environmental justice movements in our country had women at the forefront like Mayilamma and C K Janu. When women write about nature, what emerges is a nature-culture continuum which indicates the inseparability of gender, subaltern concerns, body politics, mythopoesis, place-based affiliations and environmental justice. Through their writing and advocacy, they create a subaltern “third space” that enables a new kind of knowledge generation. For example, in her interview, Kavin Malar focuses both on subaltern humans as well as subalternised nature by invoking the degradation of water bodies like the Cooum River, whose banks are cluttered with the makeshift shanties of the poor. Bama establishes the connection between the social conation of dirt, materiality and the subaltern when she shares a personal anecdote about her neighbours. Tamizhachi speaks of her bioregional mooring which is the inspiration for her poetry. Sakthi Arulanandam sums up the woman-nature connection very neatly in her poem “Of Trees”: “To see a woman’s body only as body/is like seeing a tree only as a tree.”

DR: You’ve tried to give us glimpses into the lives of so many women writers, would you please share an instance from your lives that had an impact on your writings?

SR: My creative writing is closely aligned to my academic interest—the environmental humanities. I have been deeply touched by the responsiveness of other-than human nature—nature’s voice which can erupt in brief moments of epiphany. I have a story about one such experience about a tree, which flowered at my request, in the Chicken Soup for the Indian Spiritual Soul. I have been inspired by earth stewards like the tribal activist Mayilamma, who fought the corporate giant Coca-Cola to save water in her oikos—the little hamlet of Plachimada and Dr. Rajendra Singh, the Waterman of India, who brought twelve dead rivers back to life. As a writer I feel that listening to the subaltern voices of invisibilised communities and the earth with humility and responsiveness is essential for our own survival in these troubled environmental times.

KS: I started writing when I was very young—though I didn’t think of myself as a poet until several years later. My writing, at the time, was mushy and sentimental. But I think without being quite aware of doing so I built up a practice of writing which has helped. As far back as I can remember, I have always had a notebook of some sort. To write was an impulse I could not resist or ignore for long. But I didn’t take it too seriously. I think, in those days, no one made a big deal about this sort of thing. Over a period of time, writing began to feel like somewhere I could come home to. I had a lonely and somewhat complicated difficult childhood—my mother was a divorcee back in the 1970s and we were socially very alone, outsiders, in a sense. Back then, writing was my way of dealing with the feeling of not belonging. And now, increasingly, it has become my response to the political horrors of the present.

DR: Have you, as women writers yourselves, faced any kind of difficulties in the “male dominated” literary circles?

KS & SR: As women writers, one often finds that one has fallen through the cracks of anthologies published by well-known publishers. This happens for a variety of reasons—the blind spots of those who edit these anthologies, the difficulty of networking with other writers or poets if you happen to be female and have certain sorts of responsibilities, the fact that you write in a voice that is different from the mainstream and about things that are invisible to the mainstream. But this is changing now slowly with work being published online, with the advent of social media and so on—which, with all its flaws—can sometimes help your work reach new readers.

Read More:

Malathi Maithri: “To control my language would be the equivalent of killing myself”

Nayantara Sahgal: “No mob can tell us what to write and what not to write”

Basanti: Writing the New Woman