“It is unusual to hear all those who feel moved by the deplorable condition of the untouchables, unburden themselves by uttering the cry, “We must do something for the Untouchable.” One seldom hears any person saying, “Let us do something to change the Touchable Hindu. It is invariably assumed that the object to be reclaimed is the “Untouchable”. (As) if the Untouchable can be cured, Untouchability will vanish.”

– B. R. Ambedkar’s Untouchables or The Children of India’s Ghettos

Today marks the 70th anniversary of India’s Republic Day. It is celebrated to honour the date in 1950, which marked India’s transition from a democratic government system to an independent republic. The Constitution of India, drafted by a committee led by Dr BR Ambedkar guarantees rights of justice, liberty, equality and fraternity to every citizen of India. Yet, even seventy years later, the grim reality is that inequality and discrimination loom large. An event that puts all such illusions of equality to shame is the death of Dalit scholar Rohith Vemula. His suicide brought on by systemic casteist oppression was simply not an attack on one individual but on the aspirations of an entire community. It poses the question – Is death the only thing available to a Dalit without obstacles?

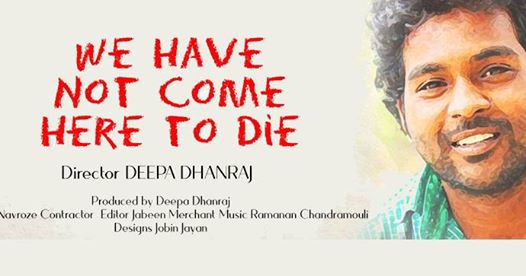

On January 17, 2019, three years after Rohith’s death, documentary filmmaker Deepa Dhanraj’s We Have Not Come Here to Die, comes as a testimony to the historic moment that galvanized student politics in India and changed caste conversations forever. It was released and screened in university spaces across India. At a time when even the fourth pillar of democracy seemed to have succumbed to the pressures and demands of fascist regimes, students spoke up. In the years following Rohith’s suicide, thousands of students all over the country have broken the silence around their experiences of caste discrimination in Universities and have started a powerful anti-caste movement. In the first scene of the film, a man is lighting the candles of the fellow men standing in a queue, in a march honouring Rohit. The communal viewing of the film pan India also lends itself as a statement of solidarity and collective resistance.

Rohith Vemula was a PhD scholar at the University of Hyderabad. He was an active member of the Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA) which was initially formed to assist Dalit students in the University. On August 3, 2015, the ASA condemned the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) protest on the screening of the documentary Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai in Delhi University and wished to organize a screening at the University of Hyderabad. The ABVP’s local leader, Nandanam Susheel Kumar, miffed by this impudence filed a complaint of assault against the “goons”. As a result of this, Rohith and five other research scholars were suspended by the university and expelled from their hostel in 2015. After the confirmation of the suspension in January 2016, Vemula committed suicide.

The film throws light on the ghettoization of Dalit students in the University space which is fraught with all kinds of gender, caste and class solidarities. When Rohith and along with other students had been suspended from the University, even the staff workers had been turned against him by Appa Rao Podile the VC of University of Hyderabad. In protest, the university students had a makeshift tent using vinyl posters in the shopping complex area of the university. Looking down from the posters were iconic figures who had battled for the rights of the downtrodden: EV Ramasamy, Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule, Bhimrao Ambedkar. The students called their protest site a velivada—the Telugu word for Dalit ghettos situated on the peripheries of villages. This was a charged statement against inequality being practised in the production of spaces. This discrimination was reflective of a larger historical social relationship, when the Untouchables were faced with barriers against – eating, drinking water, bathing, and so on, all of which were activities meant as common cycles of participation. A struggle for survival in such liminal spaces also delineates how the communities do not have the luxury of private, subjective or internal experience.

We Have Not Come Here to Die showcased the indifferent attitude of several university students on the death of a fellow student whom they claimed they had no kinship with. Calling themselves the “sufferers”, these students (presumably the upper caste) found it inexcusable that the rest of the university students had to bear the brunt of the disruption caused by the death of just one student. “He was not my brother!” one them retaliates. This instance also exposes the deeply ingrained “us versus them” idelogy that makes one immune to the pain of thers.

The film employs posts from Rohith’s old Facebook account, his images, and writings, not as nostalgia but to demonstrate the depth of the boy’s thoughts/wisdom which was beyond his years. It also highlights how online spaces have been mobilized by the marginalized when the doors of mainstream media and academic spaces were closed on them. His writings were posthumously compiled in a book, Caste is not a Rumour: The Online Diary of Rohith Vemula (Ed. Nikhila Henry, Juggernaut Books, 2016)

From a scathing political critique, the film makes a moving turn towards testimony when she shows a mother’s gaze, fixed on the photo of his son kept on stage, at a gathering organised in his honour. “I see Rohith in all of you,” she says. However, instead of being a helpless victim of her circumstance, Radhika Vemula, Rohith’s mother, emerges as a strong Bahujan woman and a force to be reckoned with. She occupied the centre stage and questions the system, “Mr, Modi recently called my son, a son of Mother India. I want to ask him, is my son an anti-national or a son of Mother India?” She travels across the country, braving arrests and attacks, to address young crowds, “Are the Universities not meant for our children?”

It was not his simply his aspiration for education or his merit that earned him the ire of the Hindu Supremacists, his ‘fault’ was that he did not want to remain invisiblised anymore, and in doing so he had shaken the foundations of years of systemic oppression. Like Vijeta Kumar wrote in her essay, “When invisible power lays its hands on you and pulls you back, you will turn around, scream back, become angry, mad, irrational and throw desks and benches like Pariyerum (From Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal) did. But to an outsider, you are a mad person who is hallucinating danger that nobody else can see.” Imagine the anguish he suffered and for how long before he took his own life.

The film asks the uncomfortable truth – Rohith Vemula may not be the first Dalit student to succumb to casteist oppression in university space, but can we pledge this Republic Day that he be the last?

Read More:

“From Shadows to the Stars”: A Tribute to Rohith Vemula

“By making the ‘anti-national’ institutions the best institutions, the government aims to privatise them”: Debaditya Bhattacharya