Universities in India have been the only spaces where students could find opportunities, and the confidence, to break social barriers. Today, however, they are being forced to rethink and redefine their role and are constantly under the scanner, with governments, political parties and other stakeholders questioning their ways of functioning.

Edited by Apoorvanand, The Idea of a University examines this unprecedented crisis through essays by teachers and academicians located in different academic spaces. They reflect on how a university works, the historical evolution of central and state universities in India, the current state of different higher academic institutions in the country and the many challenges to academic freedom. The following are excerpts from chapters “The Barbarians Have Landed” by Alok Rai and “Night-Thoughts on Academics, Administration and the University” by Ram Ramaswamy.

The barbarians have landed!

I fear that the attack on the universities that we have witnessed over the past year, the asinine chorus over ‘nationalism’, might just be the opening shots of a deeper, darker strategy. After three years of empty posturing—slogans, catchy acronyms, jumlabaazi—it is becoming apparent, even to the faithful, that the Pradhan Sevak and his team will be unable to deliver on their wider promises of inclusive growth and development. Vikaas is the mantra,1 but it is no more effective than the other mantras repeated by the faithful. Of course, the big boys will do well, and the stock market will thrive, thank you very much—until one day, it wouldn’t. But meanwhile, the vast bulk of the country, including the members of that famous demographic bulge, have only a bleak and uncertain future to look to. In fact, bleak—and certain.

Are there other possible futures out there, alternatives to the pressing dark? It will take a brave man to answer that question with a confident affirmative—but it is clear to this not-so-brave man that the only place where the possible outlines of those alternative futures can be debated, and shaped, has to be the universities where the young gather—because, again by default, they have the greatest stake in the future, and not old men in khaki shorts and saffron robes, or in faded blue jeans, for that matter. It is also clear that any such deliberative process is likely to be, and often is, perceived as a threat to the planned strategy to deliver a suitably ‘skilled’ population to service the engines of global capitalism. Orwell visualised the post-war world as being divided between three superstates that were permanently locked in a kind of hostile equilibrium, and this hostility—a state of permanent war—enabled domestic totalitarian tyrannies. The relevant detail for us here is the fact that in this projected future, there will be a remainder, ‘a rough quadrilateral [comprising of Asia, Africa, South America] … a bottomless reserve of cheap labour. The inhabitants of these areas, reduced more or less openly to the status of slaves, [would] pass continually from conqueror to conqueror, and [be] expended like coal and oil.’2 And the superpowers—the giant corporations in our globalised world—will be ‘constantly struggling’ for the right to exploit them. Us.

In this cynical strategy, suitably indigenised by local elites, civil war is not a problem: it is the solution. The strategy of setting different population groups against each other is already implicit in electoral politics, but what we have seen in recent times is a regression to a kind of ‘democratic’ warlordism, in which politics is reduced to a zero-sum game and the winning ‘tribe’, literally, takes all. This warlordism, only tenuously confined within the bounds of legality, will not take a great deal to tip over into overt conflict.

Keeping this background in mind, one can see that the attack on the universities fulfils several different functions and achieves several different objectives at the same time. At the first level, it serves to destroy the key centres from where one might have expected a critique of this suicidal strategy. Because, even in the most optimistic scenario, the best that can be expected is an Asian version of apartheid South Africa, a grafting of a couple of hundred million relatively affluent, globally plugged Indians onto a hinterland, a continent of misery. It doesn’t, quite literally, bear thinking about.

But at another level, this ‘civil war’ will serve to engage the otherwise superfluous young—the famous ‘demographic bulge’, the armies of the night—whether as goons or as their victims, as louts or their prey. It will also generate that climate of terror without which the projected and possible future will simply not be sustainable. As with that other mantra beloved of the bhakts,3 Hindurashtra, there can be no conceivable ‘victory’—and whatever could that mean, anyway? But that, once again, is merely a pretext and a formula for a permanent, unresolved and unresolvable conflict. The problem is the solution. Or is it the other way around?

[…]

Night-thoughts on academics, administration and the university

‘I don’t know what you mean by “university”,’ Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. ‘Of course you don’t

—till I tell you. I meant “there’s an impressive building for you!”’

‘But “university” doesn’t mean “an impressive building”,’ Alice objected.

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone,

‘It means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master—that’s all.’

-Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

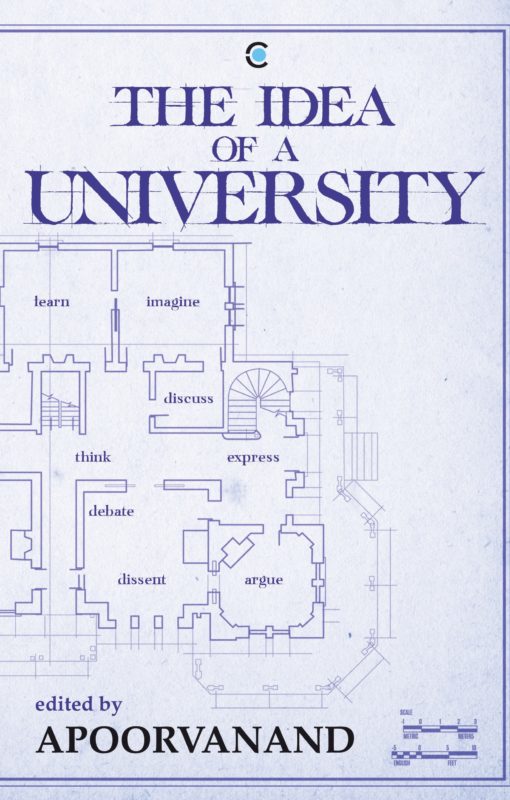

At its best a university is a place where we, as a society, can invest in our futures. Ideally, therefore, it should be a place where we can train generations of students to think, discover, innovate and invent. It should also be a place where we can archive various aspects of our society and culture, what interests us, and what makes our lives better, and should be broad enough in scope to encompass these various concerns. Most of all, it should be a place where ideas can be catalysed. As Plutarch said nearly two millennia ago, ‘For the mind does not require filling like a bottle, but rather, like wood, it only requires kindling to create in it an ardent desire for the truth and an impulse to think independently.’

Central to this idea of a university is the idea of academic freedom. An ardent desire for truth, and the impulse to think independently, requires an environment where any act of honest intellectual enquiry is treated as valid and is guaranteed a measure of respect. That such academic activities can be carried out without fear is, at the core, the academic freedom that every university requires.

India has over seven hundred institutions that are termed universities. Not all of them are recognisable as such, being highly specialised and often not much more than entities declared or ‘deemed’ to be universities so as to be able to independently give out degrees. The typical central or state universities of the country, however, offer a range of degrees in disciplines spanning the academic spectrum, from the arts and humanities, to mathematics and the sciences. But they also do several other things, some of which have little to do with education per se, and which are unique to our historical and geographical situation, and to our demography.

Protecting and ensuring academic freedom therefore needs effort and action in dimensions beyond the purely academic; the complexities of the academic workplace are often exacerbated at this time by issues that result from the rapidly changing structure of our social and political fabric. On any socially aware campus, it is inevitable that there will be some discussion on social and political issues being discussed outside the campus walls, as well as on the inconsistencies within. Preserving the right for such debate is a crucial component of what makes a university.

1. Pradhan Sevak was Modi’s proffered designation during his 2014 campaign, which was deployed to ironic effect by Vinod Dua in his TV series, Jan Gan Man ki Baat. Vikaas, or development, was what Modi promised.

2. George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Penguin edition, 1949, p. 152.

3. Modi-bhakts, RSS cadres—dedicated to the attainment of a necessarily mythical ‘Hindurashtra’.

Read More:

“The history of the University is fraught with all kinds of caste, class and gender solidarities.”

“The Fascists, in Germany too, first came after the universities”

Apoorvanand teaches Hindi at the University of Delhi and is a literary and cultural critic. He was part of the Committee for Renovation and Rejuvenation of Higher Education in India in 2009 and 2010.

Alok Rai taught English literature at Allahabad University and Delhi University and was also Professor at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Delhi. His translation of Premchand’s Nirmala was published by Oxford University Press in 2001.

Ram Ramaswamy was a professor at the School of Physical Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently President of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore.