“I don’t agree with Godard when he says that the cinema is a gun. That is too romantic an expression. You can’t topple a government or a system by making one “Potemkin”. You can’t do that with ten “Potemkins”. All you can do is create an environment in which you can discuss a society that is growing undemocratic, fascistic.” – Mrinal Sen

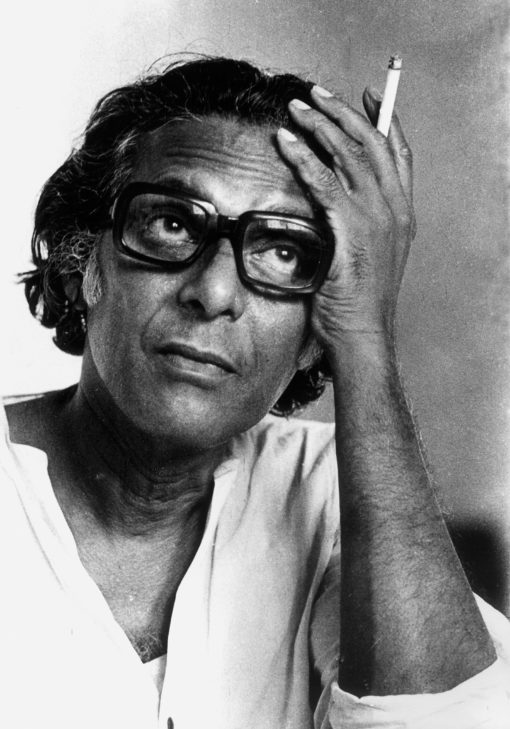

“With the passing of Mrinal Sen, the curtain has fallen on a sublime phase of Indian cinema,” wrote Salil Tripathi1. Sen died in Kolkata on Sunday after a long battle with age-related ailments. He was 95.

Mrinal Sen (14 May 1923 – 30 December 2018) was a noted Bengali filmmaker based in Kolkata. He was known as one of the pioneers of the New Cinema Movement, along with his contemporaries like Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, which brought a new dimension of aesthetic to Indian cinema, previously notorious for producing “mass hybrid escapist films in clockwork regularity2.” Sen had been conferred with the Padma Bhushan Award and the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 2003, in addition to several international awards from film festivals across the world.

Mrinal Sen made his first feature film, Raat Bhore, in 1955. Although Sen had directed five films before, it was his first Hindi film, Bhuvan Shome (1969), made on a shoe-string budget financed by the National Film Development Corporation of India, that brought him national and international fame. “The film, through a very simple and straightforward story of a widower, was narrated against the sand-filled backdrop of Saurashtra/Kutch. Enmeshed with several layers of meaning – the subtle pointer at corruption at the low ranked level, the stripping of the snobbish attitude by the high-ranking officer as he befriends a naïve and nubile young wife and so on, captured against an arid backdrop intensified the contrast between the narrative and the atmosphere,” notes Shoma A Chatterji, National Award winning author, freelance journalist, and a film scholar, based in Kolkata, India. The film said to have launched the “New Cinema” movement, won three National Awards – Best Film, Best Director (Sen) and Best Actor (Utpal Dutt). Post Shome, Sen directed a series of films about India’s contemporary socio-political conflicts such as Interview, Calcutta ’71, Padatik, and Chorus. His affiliation to Marxism, German Expressionism, Existentialism, Surrealism and Italian Neorealism had become widely acknowledged by then.

In an Interview with Cineaste3, Udayan Gupta had asked him, “Many people think that, given the social and political environment in India, it is impossible to make political films. In this regard, do you make political films or films about politics?”

To this, Sen had unequivocally responded, “I am a social animal, and, as such, I react to the things around me – I can’t escape their social and political implications. When I make a film on the relationship between a man and a woman, I try to understand the relationship in a larger context.”

Indeed in his film, Ek Din Pratidin (One Day Like Another), 1979, about a woman, the sole breadwinner of a small family, who doesn’t come home one night. Though the camera seldom goes outside the home, the film throws light on the social, political, and moral issues which determine our everyday living. The film not only won several National Awards but also received a mention in the competitive category at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival.

The collective context in which he situated his films was not just restricted to the content of his films but also translated to his practice of filmmaking. Many had noted the riveting “jugalbandi” between Sen and cinematographer K.K. Mahajan. The duo had famously created the Calcutta Trilogy comprising of the terrific three – Interview, Calcutta 71 and Padatik, among many others. Similarly, his relationship with his contemporaries(though Ray started making films from a decade ago) was one of great creative collaboration, albeit marked by moments of rivalry. In an interview4 with film critic Samik Bandopadhyay, Sen narrated one such incident. “When I completed Khandahar, I received a long fax from Cannes. My faxes would come to the Grand Hotel, in those days. They had written that although they had seen Khandahar, they could not accept two films from the same country. They had heard of Ray’s Ghare Bairey and were convinced that this was his last film because he had fallen sick while filming. They had started this festival with Pather Panchali. Let the Cannes festival end with Ghare Bairey, they requested. No one had seen his film yet. And everyone was worried – if my film won an award and his didn’t, then that itself would perhaps kill him off. They said they would extend every support to me and my film but that I must concede to this one request. They screened it, but out of the competitive section. I had nothing to say.” Ray, Ghatak and Sen were ardent admirers of each other’s work, and together charted the independent trajectory of parallel cinema. It is thus, customary that whenever any one of them is mentioned, the other two are remembered in the same vein. Directors like Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Shyam Benegal, Basu Chatterji, Mani Kaul, G. Aravindan, Kumar Shahani, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, and Mrinal Sen, who considered themselves film aficionados, were active members of the film society movement in India. Propelled by debates similar to those that animated left-oriented cultural movements which originated in late colonial India, namely, the Progressive Writers Association in 1936, and the Indian People’s Theatre Association in 1942, they broadened the definition of ‘good cinema’ – from an aesthetically sophisticated product to a radical political text8.

Another feature of Sen’s oeuvre that mightily captured the Bengali imagination was his representation of Calcutta as a setting, a character, and a muse. His films, from Punascha to Mahaprithvi, portrayed the city’s past, present and coming age of age through its people, the streets, their value systems, class differences and so on.

“As soon as I came to the big city, I was seized by a kind of fear. I confronted a crowd, a huge crowd. I felt lost. I felt I was standing alone in the crowd – an anonymous, self-absorbed, indifferent swarms of crowd, even menacing and monstrous. Loved by my parents and liked by my small town teachers, I was now reduced to anonymity, suffering acutely from a depressed sense of emptiness. Till things proved different,” he once said. This predicament of a small town boy being suddenly thrust into an ‘alien’ world is not uncommon, “unless the victim shows traces of uncommon features in himself. I was an average boy of average intelligence, and that was why I was affected so easily5.” “In retrospect, coming from a man who went on to make nearly 30 films between 1956 and 2002, this underscores how little Mrinal-da understood his own potential. As a teenager thrust into a new world, he found himself grappling with a new cultural and geographical context where the only thing in common between the culture he had left behind and the culture he had now stepped into was the language – Bengali,” remarked Shoma Chatterji.

German filmmaker Reinhard Hauff made an 82-minute documentary on Mrinal Sen on 16 mm in 1986. It was called Ten Days in Calcutta – A Portrait of Mrinal Sen. Hauff did not make an objective, biographical documentary on the director. Instead, he chose to divide his attention between Calcutta and Mrinal Sen. The film strikes a balance between Hauff’s impression of the social reality of a metropolis and as it is portrayed in Sen’s films; Calcutta as seen through the eyes of a foreigner; through the eyes of a filmmaker who has been deeply rooted to the city, a city that evokes intense love and hatred in Sen’s mind and in the minds of many others as well. Hauff sought to identify Sen’s approach to the city, its inner and outer realities, an approach that Hauff chose to describe as ‘critical realism6.

As an artist making films with sensitive and pragmatic women characters, he was a coveted director to work with. Once Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil had expressed their keenness to work with the director on his next film. Sreela Majumdar (who worked with Sen in Ek Din Pratidin) following their lead, had pitched in her request too. Sen had reassured Majumdar.”You are practically family. Stop worrying.” He went ahead and wrote letters to both Shabana and Smita. ‘You are definitely acting in my next film. But unlike Shyam (Benegal), I cannot move about with a harem, like a Mughal Emperor. He can take plenty of women at a time, but I can’t take more than one woman at a time. I start with you. After you, I’ll take on another actress. You are a great actress. So is the other one.” He addressed them as ‘Dear Shabana’ on and ‘Dear Smita’ but deliberately interchanged the envelopes and sent them off. Shyam Benegal had informed him much later that both actresses sat at the same dinner table with the letters and had a good laugh about it7. Here is rare archival footage where Sen is directing actress Uttara Baokar and Roopa Ganguly on the sets of the much-acclaimed film, Ek Din Achanak (1989). His brief instructions to them: “You are reacting to the present but your mother is reminiscing the past,” carry in them kernels of philosophical wisdom about time, temporality and transience. Uttara Baokar won the National Film Award for Best Supporting Actress (1989) for the film.

Mrinal Sen was one of the few filmmakers who was admired and celebrated both in his homeland and internationally. When the Museum of Modern Art organised Film-Utsav or The Festival of India 1985-1986 to celebrate the diversity and richness of modern India and Indian culture through art, music, dance, drama, film, and craft, Mrinal Sen was one of the distinguished directors who was profiled. The others in the list included Raj Kapoor, V Shantaram, Guru Dutt, and Ritwik Ghatak.

Documentary filmmaker RV Ramani, a self-confessed ardent admirer of Sen’s filmography, who also made a documentary on Sen, told the Indian Cultural Forum how a formal visit to Sen’s house, translated into an “informal” film on the Phalke Awardee.

“I was in Kolkata in 2013, when a few officials from Films Division under Mr. Virender Kundu, had decided to make a documentary on Mrinal Sen. They were visiting in his house to discuss the proposal with him and I being a huge admirer of his work, simply went with them. I took my camera along. At the end of the meeting, I realised that I already had a film with me.” This is the story behind his film A Documentary Proposal (2016). Ramani also quipped that at the time Sen was not convinced about Ramani’s skills and insisted that his biography only be made by another filmmaker, whom he had recommended to the officials.

Acclaimed filmmaker, Nandita Das has said that Sen “was a perfect combination of a wise-old-man and completely young at heart.” In what remains as one of his last interviews, Sen recalled,

1. Tripathi, Salil. “Curtain falls on a sublime phase of Indian cinema as Mrinal Sen passes away at 95.” Livemint. 30 Dec 2018. Hindustan Times.

2. Gupta Udayan, Sen Mrinal,Karnad Girish, Mehta Ketan. “New Visions in Indian Cinema: Interviews With Mrinal Sen, Girish Karnad, and Ketan Mehta.” Cinéaste, Vol. 11, No. 4 (1982), pp. 18-24. Cineaste Publishers, Inc.

3. ibid.

4. “Memories from Mrinal Da”. Rediff. Excerpted from Mrinal Sen: Over The Years, An Interview With Samik Bandopadhyay, Seagull Books. http://www.seagullindia.com/

5. A Chatterji, Shoma. “Mrinal Sen: ‘I wish I could start from scratch’”. Rediff. 30 Dec 2018.

6. A Chatterji, Shoma. “The Legend Lives On.” Spectrum. 25 May 2008. The Tribune.

7. see 4.

8, Mojumdar, Rachna. “Debating Radical Cinema: A History of Film Society Movement in India”. Modern Asian Studies. Vol 46. No. 3(May 2012), pp. 731-767. Cambridge University Press.

Read More:

फहमीदा रियाज़: “कभी धनक सी उतरती थी उन निगाहों में”

“On asphalt, you hold your arms out” — Remembering Meena Alexander