Thackeray, a bilingual film, starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui as lead, directed by Abhijit Panse and written by Shiv Sena politician Sanjay Raut released two trailers (Hindi and Marathi) on Tuesday. The film is a biographical drama based on the life of late politician Bal Thackeray, Founder and Chief of Shiv Sena, an ethnocentric party based in Western Maharashtra. The film is scheduled for release on 25 January 2019, the 93rd birthday of Bal Thackeray, only three months away from the Lok Sabha elections of 2019.

From the cover image to design to content, the differential presentation of the Marathi and Hindi trailers implies two different sets of viewers separated by linguistic, temporal and regional locations.

The Marathi trailer positions the film as the story of a young Thackeray, who wronged by the injustices of his current circumstances determines to start a movement to safeguard the interests of the common man. It features caustic dialogues of unabashed nativist politics, which defined the foundational phase of the Shiv Sena in the late 1960s. The Hindi trailer, intended for the North Indian audience is replete with images of Saffron in every frame in the form of flags, banners, garments and so on; focusing on the rightist and militant phase of the late 1980s-early 1990s when Thackeray had already established himself and his party, Shiv Sena, locally and was harbouring national level aspirations. The trailer propagates Hindutva-nationalism which was the stance adopted by the party in its second phase, after which it had extended alliances with the BJP.

The Marathi Trailer opens with street shots* of Mumbai with the police sirens blowing up, augmented by a warning that Maharashtra was not for the outsiders or the ordinary; it was a land of the tiger, and anyone who dared to mess with the tiger would have to face grave consequences. It adds that History had borne testament to that and the future would also stand to witness it. This is followed by big bold attributions such as ‘Ideal’, ‘Revolutionary’, ‘Activist’, ‘Fighter’, ‘Leader’ flashing across the screen. The saffron ink glaring on the stark black background foreshadows the bleakness of life in the times of saffron.

Nativism is a philosophy that is specifically anti-migrant. The mobilization of anti-migrant sentiment may rely on ethnic, linguistic, or religious loyalties, but Nativism by itself can also be conceptually and empirically differentiated from the majority ethnic nationalism(which was the stand adopted by the Sena in its second phase). In Bombay, nativist sentiment found explicit political expression in the Shiv Sena which was found in 1996 to secure the interest of the “sons of the soil.” Bal Thackeray premised the ‘movement’ on civic rather than religious lines. One of the very first scenes of the Marathi trailer showed a Muslim family sitting in the intimate, and domestic space of Bal Thackeray’s residence, possibly there for grievance redressal, is eliminated entirely in the Hindi trailer. One whole minute of the trailer, which is half of its total duration, follows a young Thackeray walking on the streets of Bombay, observing the landscape of the markets, and navigating through workspaces with resentment and a sense of alienation on billboards in Tamil, Malayalam and English. He is shown being pushed and shoved by ‘outsiders’ (a ‘son of the soil’ was anyone whose mother tongue was Marathi, or one who had lived in Maharashtra or Bombay for ten or fifteen years, or one who identified with the “joys and sorrows” of Maharashtra1 depending upon the Sena’s changing perceptions of political expediency). All these shots are loaded with audio and visual material fulfilling colossal roles. The images of a Bombay past is meant to evoke nostalgia in the heart of the ‘native’ but the sharp political commentary constantly running in the background is there to instil in him the lessons of ‘history’ as Bala Saheb wrote them. Moments later, we see an angry Bal Thackeray addressing a meeting of party activists at Amar Hind Mandal.

“[How] these salé ‘andu gundu’ South Indians come together! How they [help] make each other big in life! They bring people from their hometowns even to wash the dishes at [their street side] idli carts. But not anymore. Now “uthao lungi, bajao pungi!” he says in what is supposed to be a rousing speech 2.

Social media was quick to call out the xenophobia in these comments. Taking to Twitter, actor Siddharth termed the controversial dialogues ‘hate speech’ against south Indians:

Nawazuddin has repeated ‘Uthao lungi bajao pungi’ (lift the lungi and *’#$ him) in the film #Thackeray. Clearly hate speech against South Indians… In a film glorifying the person who said it! Are you planning to make money out of this propaganda? Stop selling hate! Scary stuff!

— Siddharth (@Actor_Siddharth) December 26, 2018

In the first years of the movement’s existence, party speeches and writings were devoted largely to the local-outsider issue. In the weekly Marathi magazine, Marmik, edited by Bal Thackeray, lists of offices, businesses and institutions, and occupations showing Maharashtrians to be a minority were printed and circulated. Protests were launched in particular against South Indian migrants who, it was claimed, had monopolized secretarial and clerical jobs in Bombay. In 1967, the Shiv Sena entered the political arena by helping Congress to defeat Krishna Menon, a South Indian by birth. In 1968, the Sena contested on its own, winning 42 out of 140 seats in the municipal election3.

While the narrative of “anti-nationalism” only enters the Marathi trailer towards the end, the majority of time is spent establishing a machismo on screen. One that is of not just any masculinist identity but a high-pitched masculine Maratha patriotism. Nawaz’s concluding dialogues on the colour of blood et all allude to the early years of Marmik, before the idea of Shiv Sena had been conceived and before there was any mention of “outsiders” or “local” people, articles on the dangers of “Lalbhai” (Red brothers) and the alleged infiltrators from Pakistan were frequent inclusions4. Communists had seemed to them a real problem.

In sharp contrast, the Hindi Trailer, specially prepared to satisfy the carnage tendencies of the north Indian right-wing sympathisers speaks to them quite literally and symbolically in a language that they understand. It opens with scenes of a riot in the city, with wailing children and terrified mothers. The narrative voice declares that there is only one man who can bring an end to this violence and peace to Bombay and shots of Thackeray’s back, men chasing his cars, follow as though welcoming a Saviour of the people. Unlike the Marathi trailer, textual interventions are not deemed as necessary to establish this point, because the North of India is too familiar with a one-man-army legend as promulgated by the BJP PM candidate of 2014. The narrative progresses rapidly and in an unrestrained manner much like LK Advani’s Ram Rath Yatra of ‘90, and wastes no time establishing Bal Thackeray as a leader of the common man, possessing strong and rather militant ideas of justice. This image and imagination of the rise of a common man, who comes from within the people and fights for the people, is one that was capitalised by Narendra Modi all through his campaigns and continues even his post-election speeches. Intended to challenge the alleged aristocratic leadership of the Congress, which only serves the interests of the elites is a narrative that will immediately strike a chord with his Hindi speaking voters. Though ostensibly it enables autonomy and responsibility in the public or the collective, what it actually proliferates is what the social media calls as ‘mobocracy’.

Image Courtesy: Zeitgeist Films

Image Courtesy: Zeitgeist Films

In Chaitanye Tamhane’s acclaimed film, Court(2014), there is a sequence where the public prosecutor played by Geetanjali Kulkarni is enjoying a day out with her family. The parents and children indulge in several recreational activities, like eating out, visiting parks and zoos and so on, much like a regular middle-class household. They also go to see a Marathi play at one of the local theatres (The wall beside the stairs that lead up to the auditorium are lined by photos of Maratha heroes from history). The play is a comedy about a Marathi girl falling in love with a North Indian boy (not innocently named Prem, who enters the stage singing, Le Jayenge, Lejayenge UP wale dulhaniya le jayenge) and having a hard time convincing her father to let her marry him. To convince the father, the girl makes up a bunch of lies about his real identity, but the father is too worldly wise to be fooled. He goes pointing faults in the boy beginning and exposing his inadequacies but the seemingly private domestic issue suddenly turns into a commentary on nativism. The father grabs his old servant and the boy by their hand and makes them stand one on each side, so now all three men stand to face the stage. He shouts at them, “You immigrants, first you steal our jobs, then our land and now want to steal our daughters as well?” and kicks them out of his house. Then the tilak bearing man, begins his monologue, directly addressing the audience, “They mistake our grace for weakness. But if pushed, this Marathi Manus(man) can easily show them who is the boss in this city.” He is received with thundering applause and cheers and whistles. The scene in the (Hindi trailer) of Thackeray, where the poster (and implied screening) of a Hindi film is taken down and replaced by a Marathi film, as Thackeray declares, “Ab yeh sab yahan nahin chalega. Pehla haq yahan ke Marathi logon ka hi hai. (It can’t go on like this. From now on its, Marathas first,” echoes this sentiment.

The Hindi Trailer has an additional dialogue where Thackeray is speaking with two cricketers regarding their appeal for an Indo-Pak series, which in their opinion would promote peaceful relations among the nations. This alludes to the incident when a few party workers even dug up the pitch in Wankhede to prevent an Indo-Pak test series in 1991. Thackeray responds with the jingoism that every right-wing North Indian loves – that he could not betray the martyred sons of the forces. In doing so, he echoes the same resurgent nationalist sentiment of the deployed by the BJP in their contemporary politics.

Next, we reach the pinnacle of the far-right imperial motives with the incident of the demolition of the Babri Masjid. The Srikrishna Commission Report that came out in 1998, five years after the riots took place, underlined the Shiv Sena’s malevolent role in the communal riots in Mumbai in December 1992-January 1993, and pointed to the contribution of the BJP in the build-up to the violence. The report determined that the riots were the result of a deliberate and systematic effort to incite violence against Muslims and singled out Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray and Chief Minister Manohar Joshi as responsible. The Sena-Bharatiya Janata Party Government in Maharashtra had rejected the core of the report, on grounds of being “anti-Hindu, pro-Muslim and biased”. Thackeray had even gone on to accuse Justice Srikrishna, an eminent and respected sitting Judge of the Bombay High Court, of bias5. LK Advani’s speeches during the Rath yatra where he overruled the Court’s warnings over a public idea of ‘justice’ was along the same lines.

Image Courtesy: The Wire

Image Courtesy: The Wire

This insolence glorified as heroism, of running a parallel government and wielding more power than the leaders of state served as the core of the Shiv Sena Chief’s governance model. Founded upon absolute and essentialist ideas of justice which had become corrupted by systems of power, Thackeray saw himself as a revisionary who would reclaim it for his people. The dialogue, “Aap mujhe judge karne wale kaun hote hain? Main sirf ek adaalat ko manta hun, aur woh hai, Janta Ki Adaalat”(Who are you to judge me? I do not believe in your institutional notions of justice, I only believe in the verdicts of the common man.) – were the swansongs of the Shiv Sena, and swooned mass voters.

Deriving its name from Shivaji Bhonsle, the seventeenth-century founder of the Maratha empire who, among his many deeds, is famous for his defence of the Maratha territory against the incursions of the Moguls from the North, the Shiv Sena calls itself an “army of Shiva”. In the past few years, images of PM Modi paying homage to the statue of the 17th century Maratha king, have resurfaced, thus, pointing to a long-strategized move ahead of the elections to secure votes of the lakhs of followers of Thackeray, particularly in Mumbai and Pune. Anand Patwardhardhan’s latest film, Vivek(Reason) (2018), raised questions on these convenient ploys of political parties, competing for claims on Shivaji. In a comic yet scathing scene, activist and writer Govind Pansare makes a speech on stage, addressing a meeting where he draws from history books to ask, “Shivaji never called himself a protector of either cows or Brahmins? So, who put the tag? Surely, must have been one of them, but if it weren’t the cow, then?”

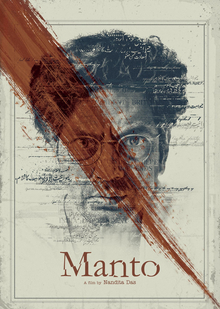

Yet, the question that disturbs me the most is what credentials do I attribute to Nawazuddin Siddique who played the titular character in the Nandita Das directed biographical drama Manto, and now undoes the whole legacy of Sadat Hassan Manto by playing someone like Bal Thackeray in a film releasing not even six months apart?

Here Nawazzuddin goes gaga over the chauvinism he has inherited simply by getting into Bal Thackeray’s shoes. He adds that he has now become fearless(like the leader), “Itna assar mujh pe aa gaya hai ki main abhi darrta nahin hun.”

The teaser launch event of the film was performed by none other than the legend-opportunist of the millennium, Amitabh Bachchan, who sung encomiums about his intimate relationship with the deceased founder of Shiv Sena who he revered as a father figure. He even implored the producer to not stop at one film, but make ten films so people could really get to know the many facets of his personality. One might recall that his character in Ram Gopal Varma’s Sarkar, a remake of Godfather, was a problematic glorification of Bal Thackeray’s life. In the same event, Nawaz had said that to play such a character was an actor’s dream, “Duniya ka koi bhi actor karna chahega!” This apolitical distancing of the art from the artist or of art from reality, is a long cloak of hypocrisy worn with pride by mainstream Hindi cinema, because as the January roster of Hindi films go with Uri, and The Accidental Prime Minister all lined up, these pretensions are soon falling off.

1. F. Katzenstein, Mary. “Origins of Nativism: The Emergence of Shiv Sena in Bombay”. Asian Survey, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Apr. 1973), pp. 386-399. University of California Press.

2. ‘Hate speech’ against south Indians in Thackeray biopic trailer, actor Siddharth objects

3. F. Katzenstein, Mary. “Origins of Nativism: The Emergence of Shiv Sena in Bombay”. Asian Survey, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Apr. 1973), pp. 386-399. University of California Press.

4. Ibid.

5. R. Padmanabhan. “The Shiv Sena Indicted”. Frontline. Vol. 15: No. 17: August 15 – 28, 1998. The Hindu.

Read More

Lynch Nation: “The film doesn’t talk, but listens”

Seeing Reason in Anand Patwardhan’s Latest Documentary Vivek