Image Courtesy: Ananda Bazaar

Image Courtesy: Ananda Bazaar

Kalpana Lajmi, the courageous director who passed away recently, had directed only a handful of films but each one critically explored the woman question powerfully. Among all her films, the one that remains timeless in its significance and also a milestone in cinema springing from literature is Rudaali. The timelessness of the story, however, is not confined to its gender focus but also, like the author of the story, Mahasweta Devi, showed, about how gender is subsumed into the discourse of class. To emphasize the former at the expense of the latter is a ‘denial of history as she sees it’1. The two together lead to the third dimension of the oppression – poverty. Rudali was originally written in Bangla in 1979 and was adapted into a play by Usha Ganguli in Hindi, a leading theatre director from Kolkata. Anjum Katyal translated the short story, Rudali into English in 1997 and the film, Rudaali was made in 1993. The three representations of Rudali – the story by Mahasweta Devi, the play in Hindi by Usha Ganguli and the film in Hindi by Kalpana Lajmi, have one common strand running along them – they are all authored by women. Each version – fiction, play and film – is mediated by the differing purpose and agenda of its respective auteurs, resulting in strikingly different texts which have one feature in common – they and are widely perceived as woman-intensive projects and received as feminist texts2.

The term “rudaali” literally means a female weeper. Rudaalis are a group of professional mourners who are called upon to shed synthetic tears, cry loudly and beat their chests for money when someone important and affluent dies. It was a new addition to the lexicon of Indian literature, thanks to Mahasweta Devi who introduced this term and its socio-political ramifications within little-known pockets of tribals and other neglected groups in the country. Devi is looked upon as an icon in Indian literature. She persistently worked around the notion of the subaltern3, their “silences” and suffering amplified by caste, and class, in the landscape of Indian society. Rudali is relevant even today for its powerful treatment of the deeply entrenched social and political ramifications of caste-based discrimination. The story speaks of the ghettoisation of women, particularly those belonging to the said Dalit communities, by confining them into an occupation that is exclusively a female domain. These women find themselves trapped in the business of selling tears and its associated paraphernalia – wailing loudly, rolling on the floor, chest-beating, manufacturing tears and so on just to keep body and soul together.

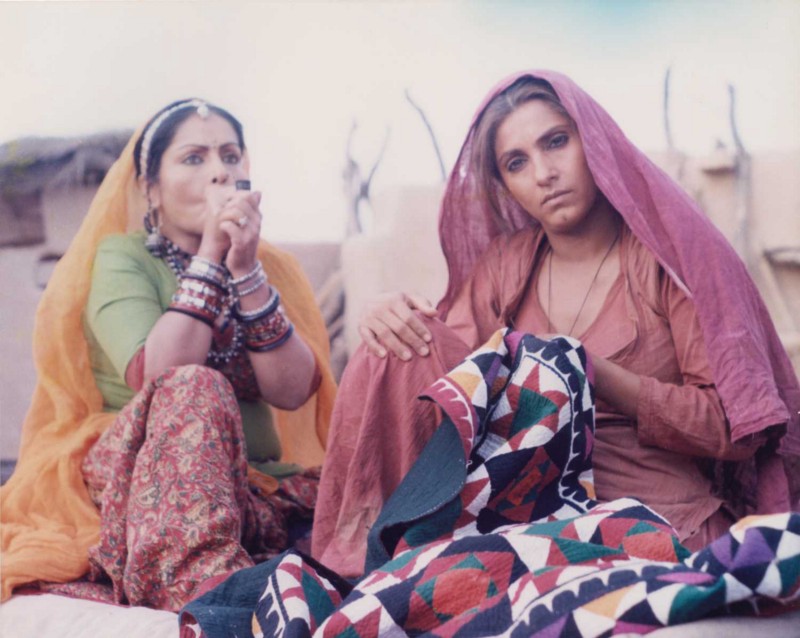

Kalpana Lajmi’s film, Rudaali is set against the physical and cultural backdrop of rural Rajasthan. It revolves around the life of Shanichari, a woman belonging to the most impoverished lot of the village population. Her father dies soon after her birth and she was abandoned by her mother. She is married to a man who works as a bonded labourer at an upper caste landlord’s house. Her husband is a drunkard with little to spare for the family requirements. She looks after her ailing mother-in-law and her little son. As the story progresses, she loses both her mother-in-law and her husband. Her son runs away after growing up.

Image Courtesy: Medium

Image Courtesy: Medium

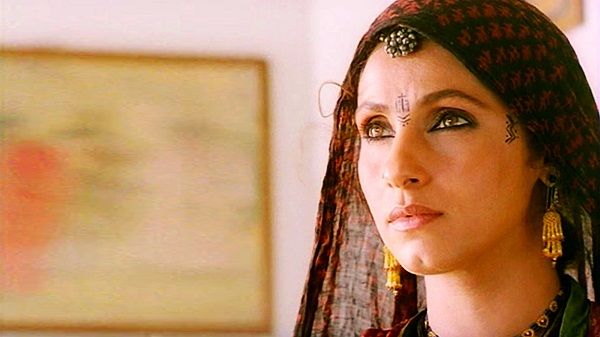

Having suffered all her life, Shanichari(Dimple Kapadia) discovers that when she becomes the heir to her mother’s profession for the first time, her tears have dried up and the ‘cry’ just fails to come. She cries, at last, drawing upon her personal tragedy. She learns that the professional mourner from another village Bheekhni(Rakhee), who she had developed a close bonding with, has died of smallpox. Bheekni was the mother who abandoned her when she ran away with another man. When the landlord dies, Shanichari’s pathetic wails pierce the silence of the sky, the horizon, till they bounce off from the high walls of the zamindar’s haveli. These scenes are dotted with the use of black for the long robes the rudaalis wear as they beat their chests and roll on the floors, the air dotted with their loud wailing, manufactured to keep body and soul together. Though paid for in cash and in-kind yet their livelihood remains at the bare subsistence level.

Dr Mahua Bhowmick, in her paper, “Rudali, the Mourner: The “Cry” of the Margin4” writes:

Rudali, a custom of professional mourning prevalent among the lower caste women of rural Rajasthan for the deceased males of the upper castes, is a culture which can be regarded as a site of contestation where gender, class, caste and economic status are intertwined. This culture of publicly expressing essentially private emotional experiences – grieving and crying – is rarely considered as a creative practice. Abject poverty and social oppression drive these women to such a dehumanised state that they become compelled to earn their living by displaying their heart-wrenching sorrow in the service of the wealthy upper castes who can, as it were, purchase their tears.

Rudaali calls forth multiple worlds of debate, discussion, questioning, research and analysis. On the one hand, it explores the concept of the working woman living in desperate poverty, engaged in an occupation that is entirely dependent on the death of an affluent man. On the other hand, it looks at the woman question surrounding a mother and daughter where the daughter has been widowed at an early age. There is also the question of caste because Shanichari, the rudaali, belongs to a low caste in the caste hierarchy and is a social outcast. She survives by selling old clothes at a temporary shed, where she is teased and taunted by the upper caste male shopkeepers for being a low caste, poor and single woman without a man’s support.

Kalpana Lajmi’s film takes the root of the story and then changes it to suit the demand for glamour and glitz of Bollywood cinema with top stars, lavish mounting and high colour. Mahashweta Devi’s Rudali is originally placed in Tahad village of West Bengal where the low caste untouchable tribal people Ganjus and Dushads are compelled to live an afflicted life under the repression and tyranny of the upper-caste Rajputs who enjoy their so-called “inborn privilege” of owning the land of these tribal people by hook or crook. Lajmi shifts the geographical backdrop to a village in Rajasthan that offers the scope for exploiting the colours of Rajasthan and enriched the scope of the film by placing songs the music of which was composed by the late Bhupen Hazarika who generously drew upon his root Assamese melodies to offer a beautiful blend of the music and the visuals representing two different cultures.

In Mahasweta’s Rudali, echoed in Lajmi’s film, Devi portrayed the Rajputs as debased humans who would rather indulge in hosting extravagant and sumptuous funerals than pay for the treatment of their ailing relatives. They are so insensitive that they do not have any time to mourn the death of their loved ones so they hire rudaalis to make the genuine show of mourning scene. The Rajput wives in the landlord’s home are not permitted to express their grief or even come out of their confined spaces to join the rudaalis as the latter belonging to a lower caste, are treated as untouchables and outcasts. No one even bothers to ask these Rajput wives if they felt like crying to express their grief.

Lajmi’s directorial works are filled with a lot of pomp and style that does not go well with the raw reality and ugly poverty of Mahasweta Devi’s stories. The original story was stripped completely of melodrama or attempts to garner sympathy for Shanichari and Bheekni’s terrible state. Lajmi is unable to give Rudaali, the film, a distinct identity of its own. Despite choosing ‘women’ as her beat that informs all her feature films, she loses out to the lavish mounting and the musical gimmicks of commercial cinema. Lajmi has structured the film as a dialogue between an ageing Shanichari who is not yet a “rudaali” and her new-found friend Bheekni who has been commissioned by the landlord’s employees from another village to wait for the ritual crying and weeping when the patriarch finally dies. It is Bheekni who keeps telling Shanichari that she will teach her the rudiments of being a rudaali and earn some money.

In a flashback scene, we see a brief romantic liaison between Shanichari and the landlord’s son which pushes the young man to hire her services as his wife’s special maid. This does not exist in the story. In hindsight, one may even call it a blasphemy on the original because Shanichari’s life is so preoccupied with how and where the next meal will come from that romanticism does not exist in the lexicon of her life. The caste-ridden values of the community and the patriarchal attitudes of the affluent represented by the landlord’s young son (Raj Babbar), would never deign to even talk to a low caste woman ever, much less to ask her to raise her head and look into his eyes!

There are moments in the film that offer us a wee glimpse into the expendable lives of these Dalits. At a village fair, the milk used to bathe the gods is given to the low castes. Many of those who drink the milk, including Shanichari’s husband, die of cholera but there is no investigation. Another scene shows Bheekhni haggling over the price for mourning over the patriarch’s death including “extras,” or separate “rates” for weeping, beating chests, rolling on the floor, and so on. Her matter-of-fact manner of haggling shows the nature and degree of oppression they live within without questioning the inhumanity of the system.

Image Courtesy: Post5 theatre

Image Courtesy: Post5 theatre

Lajmi’s fondness for spectacle tends to diffuse the focus of the film never mind the three National Awards – Dimple Kapadia (Best Actress), Samir Chanda (Best Art Direction) and Dimple Kapadia (Best Costume). Late film scholar and critic Chidananda Dasgupta rightly said, “Spectacle creates distance between the observer and the observed; the understanding of the mind of the human being in a predicament requires closeness between the observer and the observed, asking for the removal of all sights and sounds.”

Lajmi loses out to the lavish mounting and the musical gimmicks of commercial cinema. She ends up denying the film the identity it deserves. Rudaali was a brazen, commercial film spilling over with the commercial ingredients of big stars, wonderful music, hummable songs, excellent production values, picturesque landscape and so on. So, Lajmi did not really need the framework of a famous Mahasweta Devi story to fall back on. As a celluloid representation of a Mahasweta Devi story, Rudali fails. But as an independent film, separated from the Mahasweta link, it is entertaining, educative and tries to inform the Indian audience about the oppression of a people it hardly knows anything about.

1. Comment by Samik Bandyopadhyay during the interview with Mahasweta Devi.

2. Pandey, Rajesh: U. R. Ananthamurthy’s Samskara and Mahasweta Devi’s Rudali: An attempt to voice the Unvoiced, Research Scholar, An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations, Volume II, August 2014.

3. The term was adopted by Antonio Gramsci, an Italian social theorist in his Prison Notebooks.

Ranjit Guha in his essay, “On Some Aspects of the Historiography of the Colonial India” defines the subaltern “as a name for the general attributes of the subordination in South Asian Society, whether this is expressed in terms of class, caste, age, gender and office or in any other way” (216). Source: www.cacsarchive.org/dataarchive/otherfiles/TA001125/file.

4. Bhowmick, Mahua, “Rudali, the Mourner: The “Cry” of the Margin”. Episteme: an online interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary & multi-cultural journal, Volume 4, Issue 1, June 2015