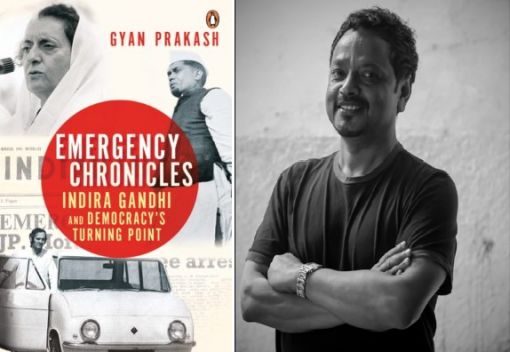

As the world once again confronts an eruption of authoritarianism, Gyan Prakash’s Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point takes us back to the moment of India’s independence to offer a comprehensive historical account of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency of 1975-77. By delving into the chronicles of the years preceding the Emergency, the book reveals how the fine balance between state power and civil rights was upset by the unfulfilled promise of democratic transformation.

Drawing on archival records, private papers and letters, published sources, film and literary materials, and interviews with victims and perpetrators, Prakash explains how the growing popular unrest disturbed Indira’s regime, prompting her to take recourse to the law to suspend lawful rights, wounding the political system further and opening the door for caste politics and Hindu nationalism.

The following is the second excerpt from the book. The first part can be read here.

Bodies and Bulldozers

[…]

The Fact Finding Committee on the Turkman Gate firing aptly called the changed shape of administration and politics the “Depoliticisation of Politics and the Politicisation of Bureaucracy.” The channels of political representation stood blocked, and the administration acted on the orders of the political masters without legal authority. As demolitions continued for several days after April 13, the tide of anger kept rising as bulldozer engines roared and sledgehammers reduced shops and homes to rubble. Trucks hauled away the debris and dumped the displaced residents at resettlement colonies across the Yamuna River. The only break came on Sunday, April 18 when the DDA bulldozers took the day off. Some Muslim residents went to Jagmohan and pleaded with him to resettle the displaced in one colony rather than scattering them in several. Jagmohan exploded in fury: “Do you think we are mad to destroy one Pakistan to create another Pakistan?”1 Meanwhile, the sterilization squads did not take Sunday off. They set about operating on people in makeshift mobile centers as the price for allotments in resettlement colonies.2 The dam broke on April 19. The residents battled the DDA bulldozers and police all afternoon, exchanging brickbats and bullets. By evening, the Walled City was a scene of carnage.

Undeterred by the local resistance, the bulldozer engines began whirring again after the police firing and under the cover of curfew. To add insult to injury, the Delhi administration issued a stout defense of Rukhsana. In a press statement released on April 19, the lieutenant governor denounced the “vested interests” determined to impede the family planning program and fulsomely praised her work. It was because of “the persistent efforts of the Motivational Committee on Family Planning headed by Smt. Vidyaben Shah, President, New Delhi Municipal Council, and Rukhsana Sultana Saheba, 15,000 persons male and female have offered themselves voluntarily for measures which will check the reproduction of unwanted children permanently.” What is more, Dujana House had “treated” over three hundred family planning “cases” in just four days since its inception.3

After the resistance was brutally suppressed with bullets and wanton violence, the victor toured the scene of his conquest the next day.4 Predictably, DIG Bhinder escorted Sanjay. After spending barely ten minutes surveying the rubble at Turkman Gate, Sanjay returned to his residence. A little later in the day, he went to Irwin Hospital, again accompanied by the ever-loyal DIG. Sanjay thanked the injured policemen, ignoring the civilians who had been injured at the hands of the police, and returned home. With the victory lap taken, Bhinder turned to covering his tracks. The police party under his leadership had fired without the legally required written authorization from a magistrate. The accompanying magistrate N. C. Ray declined to sign a post facto order, pleading that he was not present at the spot when the firing occurred. He was summoned to the prime minister’s residence, where Bhinder, in Sanjay’s presence, insisted that he sign an authorization. Ray saw the writing on the wall and signed the order a few days later, absolving the DIG from the charge of ordering an unauthorized firing. Of course, Bhinder later denied that he had been at any such meeting, though he had no explanation for the wireless message in the police log, summoning him to the PM’s residence on that day. As in his conduct in the abduction of Prabir from JNU, Bhin- der had managed to cover up his actions with the fig leaf of dodgy legality. Such dubiously lawful authorizations of unlawful conduct captured an essential element of the Emergency regime.

Meanwhile, demolitions continued in Turkman Gate. According to official reports, at least 120 pukka (permanent) structures were razed between April 13 and 27, affecting 764 families and 199 commercial establishments. The DDA prepared a new plan in July 1976 for the cleared area, proposing a commercial project to build a tower with 44 floors and a two-level basement. The chief town planner objected, pointing out that the project changed the prescribed land use of Shahjahanabad. But the central government overruled him and gave its approval.86 What of the people whose shops and homes were reduced to dust? An eyewitness report circulated clandestinely at that time depicted their plight as “indescribable.”

They are packed into trucks and carried miles away from their demolished homes. They are unpacked, and the trucks leave them in vacant lots with no amenities, not even drinking water; and miles away from their places of avocation, and without any alternate work in the areas to which they have been forcibly shifted.

[…]

Freedom behind Bars

“Writing letters is a hugely calming activity in the loneliness of the prison. These letters are meant for other people of course, but they are also a great way to hear oneself think, to hear oneself sort out one’s own feelings and thoughts.” This was the socialist leader Madhu Dandavate (1924–2005) reflecting on letter writing in one of his letters to his wife and comrade in politics, Pramila Dandavate (1928–2002).5 Madhu, a Member of Parliament elected from Maharashtra, was arrested on June 26 and lodged for eighteen months in Bangalore Central Jail.

Pramila was taken into captivity on July 17, 1975, and was held in Yerwada Central Prison, near Pune. During the time that they were kept over five hundred miles apart, the two wrote to each other every week, exchanging nearly two hundred letters.

Politics is understandably prominent in the Dandavate prison letters. Both were seasoned political activists. Madhu first became politically active in the 1942 Quit India movement, which brought the socialists, including JP, to the public stage as an inspiring new force. While earning graduate and postgraduate degrees in physics in Bombay, Madhu was drawn to the social- ists. When they parted from the Congress after Independence and formed the Socialist Party in 1948, he joined them. He taught as a professor of physics while participating in political activities. In 1971, he was elected to the Parliament from a Maharashtra constituency, a feat he went on to repeat for five con- secutive terms.

Pramila was also a political activist, who found her socialist calling first in the Rashtra Seva Dal, an organization of volun- teers founded in the 1940s by Sane Guruji, a revered figure in Maharashtra, and other socialist intellectuals. It promoted social change, secularism, and a decentralized socialist agenda. Participation in its activities brought her into the circle of so- cialists in Bombay, including Madhu. With senior socialist leader S. M. Joshi acting as the matchmaker, she married Madhu in 1953 and became his partner in politics. Elected in 1968 to the Bombay Municipal Corporation, Pramila made her mark in the fiery protests of Bombay women against rising prices in the early 1970s. As thousands of women took to the streets, shak- ing their wooden rolling pins to remonstrate against the rising cost of food, a trio of leaders—Mrinal Gore, Ahilya Rangnekar, and Pramila Dandavate—emerged as the face of this new militant movement. Not surprisingly, all three women were arrested and imprisoned during the Emergency.

[…]

As if on cue, Madhu told her that after two and a half months of research he had finished drafting two chapters of a projected book on Marx and Gandhi.6 It was not “great literature” but it was a comparative analysis of the two paths to revolution, one based on class struggle and the other on individual change in human beings. Speaking of the experience of writing, Madhu stated: “Amidst the roses on the table and the champa [frangi- pani] flowers on the trees, the pen moves in speed and smoothly.” Then he quotes from Byron’s Don Juan: “There’s music in the sighing of reeds / There’s music in the gushing of a rill / There’s music in all things, if men had ears / Their earth is but an echo of the spheres.” Madhu had found in Byron a way to identify even in the confines of the prison an underlying and universal human spirit expressed in the musical rhythm of the pen on the page, in the blossoming of flowers. All was not lost. He tried to lift Pramila’s spirit. “Your last letter had a shadow of sadness over it. You said that our home and life together would be completely destroyed by the time we get out of here. And you don’t know if you have the strength and persistence to do it all, all over again. Your comment felt exceedingly hopeless to me. We have always carried our life together on our backs. As long as our spine is in place, who can possibly touch our life together?”

[…]

Underlying the Dandavates’ commitment to revolution was their staunch advocacy of freedom. Poetry, once again, came in handy to express their advocacy and explore the depth of the meanings of freedom. Pramila sent Madhu two Marathi poems. One called “Bhinta” (The Wall) by the famous poet Mangesh Padgaonkar had been published in a special 1976 Diwali issue of the magazine Marathawada. She transcribed the poem for him.

There is a wall around me.

A wall around you

Walls everywhere you look

Walls all around

A wall of fear

Walls have ears

And so each wall has

A fear of other walls

Every small wall

A large wall.

Invisible. Suffocating.

Stand before the wall

Snip off your tongue and stand before it

Stuff your ears and stand before it

Close your eyes and stand before it

Sit down, stand up,

Hold your ears, stand up

Someone has disappeared

But no one remembers who

Three lost their eyes

But no one remembers who

Join in with your voices and shout the slogan:

“All walls for the welfare of all”

One didn’t join in

He is nowhere to be seen

But no one can tell who!

The walls will become a habit

A wall of habits

The wall needs discipline

Discipline needs walls

One two three four

The wall makers are smart for sure

Say “Hail the walls . . .

Salute and hail the walls”

She transcribed a second poem called “Mukt” (Free) by Kusumagraj, another noted Marathi poet.

A cage is broken

And the free bird

With the blood from its wounded wings

Draws red winding lines

On the green soil

As it flies.

Flies towards its nest, Perhaps,

Towards its death But—

The sky that looks at it with sympathy

Cannot take away from it

Its blood-soaked happiness . . . pride

Of having broken the cage.

[…]

Epilogue

Every year on June 26 Indian newspapers publish articles remembering the day in 1975 when Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency…The commemoration of the day, however, portrays the Emergency as a momentary distortion in India’s proud record of democracy. The experience appears as a nightmare that began shortly before midnight on June 25, 1975, and ended on March 21, 1977. The revelations of the Shah Commission and the books and articles written by journalists and those who were witnesses and victims have contributed to the powerful and enduring myth that the Emergency dropped from nowhere and vanished without a trace, leaving only its villains and heroes. The twenty-one months is sequestered as a thing in itself. We should never forget the episode that thankfully terminated without an afterlife.

This view inspires a smug confidence in the present, fore-closing any critical inquiry into its relationship with the past. It tells us that the past is really past, it is over, it is history. The present is free from its burdens. Indian democracy, we are told, heroically recovered from Indira’s brief misadventure with no lasting damage, and with no enduring, unaddressed problems in its functioning. The parallel between this account and the story told in the United States after the Watergate scandal is striking. There, too, the narrative recounted after Richard Nixon’s resignation in the wake of the revelations of his political skullduggery was that the system had worked. The free press had spoken truth to power, the Congress had played its role, and law and the constitution had triumphed. All was normal again. This account shut out any inquiry into the under- lying malaise and chicanery in the political system, as well as the possibility that they persisted well after Nixon’s ghost, had been exorcised.

Like the post-Watergate narrative, a limited view of the Emergency prevents an understanding of its place in India’s historical experience of democracy. Underlying it is an impoverished conception of democracy, one that regards it only in terms of certain forms and procedures. The constitution provided for elections, judicial independence, press freedom, and Fundamental Rights as the cornerstones of democracy. But these constitutional principles exist in society; the substantive functioning of democratic institutions and procedures depends crucially on the social and historical context.

In today’s India, as in many other places, power and money define the context. Those who enjoy social and economic privileges, and can summon powerful political influence, play by different rules. Vast quantities of unregulated capital let loose by the neoliberal economy slosh around to twist the machinery of laws and administration. An army of fixers and middlemen operate at every level to distort and corrupt the everyday experience of democracy, turning it into “a feast of vultures.” Indian politics always had intermediaries who mediated between society and the government. Traditionally, they were members of political parties. But Sanjay brought in a new group of influence peddlers—officials, friends, social climbers like Rukhsana Sultana, and individuals with links to corporations. Since then, the fixers have carved out an indispensable position as mediators between political parties and corporations. The scandals periodically unearthed by investigative journalists about the “hidden business of democracy” expose the rot in the system, the easy moral principles of the rich and the powerful. But underlying these twenty-first century scandals is the longstanding issue of Indian society’s troubled relationship with democratic values.

No one was more acutely aware of this issue than Ambedkar. He is regularly celebrated as a Dalit icon and a constitutionalist, but, with notable exceptions, few return to the full meaning of his judgment that democracy was only a top dressing on the Indian soil. For him, democracy was not just procedures but a value, a daily exercise of equality of human beings. Constitutional principles and institutions were to bring into practice what did not exist in the deeply hierarchical, caste-ridden Indian society; they were not ends in themselves. If democracy was to mean self-rule, then caste hierarchy and social inequality were alien to it. Secularism and pluralism, the opening to minorities, and the care for the Other were part of equality as a democratic value.

Convinced that Indian society lacked democratic values, Ambedkar placed his faith in the political sphere. There was something Tocquevillian in this belief in the reconstitution of society by politics. Accordingly, he wrote a constitution that equipped the state with extraordinary powers. He and his fellow lawmakers expected that the state would accomplish from above what the society could not from below. This was also a reflection of the lack of full popular consent for the nationalist elite’s power. For all his concerns about inequality, Ambedkar also worried about the danger posed by “the grammar of anarchy” of popular politics. Additionally, the postwar turmoil and the violence of Partition drove lawmakers to craft a powerful state that would secure national unity. They set aside the criticisms of emergency powers and the removal of due process and restrictions on rights to freedom. But the choice of social revolution from above placed a heavy reliance on the leaders’ moral commitment to democratic procedures. It envisioned that the elite would somehow overcome class and caste pressures from society. Here, the record is an abject failure…

After Nehru’s death, the political elite became consumed with scheming to main- tain power in response to the rapid unraveling of state society relations. Even JP vacillated between the desire for a real democratic transformation of Total Revolution and a purely political movement to dislodge Indira and the Congress. When politics became only a chess game of power, Indira proved to be a grand master, repeatedly checkmating her opponents. The queen cleared the board.

The Emergency was her masterstroke in this tactical game, a last ditch attempt to get through the crisis confronting her personal power. Extraordinary laws already existed on the books, but it was she who paradoxically used the lawful suspension of existing laws to create a state of exception to deal with the impasse. The “misdeeds” and “malpractices” of the notorious slum clearance and sterilization campaigns were not new; they were elements of the state’s modernization project from above. But in escalating and intensifying them with wanton force, Indira, with Sanjay and his coterie, sought to accomplish what they could not achieve “normally.” She tried to resolve the crisis of governance by making manifest what was latent in the constitutional structure. It is in this respect that she revealed herself as a sovereign in Carl Schmitt’s sense.

The Janata government repealed several of the egregious laws enacted during the Emergency. But its second thoughts on preventive detention and the Charan Singh government’s proclamation of a presidential ordinance on the subject indicates that the Emergency had succeeded in normalizing it. Upon returning to power, Indira regularised the ordinance by enacting the National Security Act in 1980, providing for preventive detention. The Armed Forces Special Powers Act, first applied to Assam in 1958, extended to Punjab in 1983, and to Kashmir in 1990, empowers the army to treat “disturbed” areas as warlike situations. The colonial era sedition law enshrined in Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code continues to be on the books and to be used for political purposes.

[…]

It was the fear of such political violence that explains the Indian state’s appreciation for extraordinary laws. This is why the short lived Charan Singh government brought back preventive detention in spite of the Janata Party’s rhetoric about fully undoing the Emergency. This is not, however, the only indication that the Emergency enjoys an afterlife. The social and political crises that it unsuccessfully sought to resolve with shadow laws and authority gave rise to fresh challenges. Backward caste politics, Hindutva, and market liberalization emerged out of the Emergency’s ashes to meet the tests posed by popular mobilisation. These have come to predominate the Indian political landscape since the early 1990s, and each one of these holds implications for the meaning of democracy.

The caste-based discourse addresses democracy’s concern with equality. In this respect, the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations on reservations for backward castes has produced a sea change in Indian society and politics. But caste politics has also reduced equality to the limited goal of grabbing a share of power rather than instituting it as a value. This is particularly true of regional caste-based political par- ties, which often function as fiefdoms of leaders who came of age during the Emergency.

Hindutva is fundamentally antidemocratic. It seeks to resolve the crisis of governance by building a Hindu nation with a ressentiment-driven majoritarian politics that reduces the minorities to second-class citizens. Also antithetical to democracy is the neoliberal market-based ideology that treats the market as the underlying principle of all domains. In contrast to the classical liberalism of Adam Smith, which was concerned with trade and production, neoliberalism economizes everything. Instead of the guarantee of equality through the rule of law and participation in popular sovereignty, it offers the market logic of winners and losers.7

Neoliberalism is a global phenomenon, implemented with different methods in different places. In India, the neoliberal logic, emerging as state policy in 1991, is encapsulated today in the catchphrase “development.” Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 with development as his winning slogan. Against a Congress government marred by corruption scandals and stigmatized for its supposed “appeasement” of the minorities, the BJP trumpeted the so called achievements of the “Gujarat model” of development under Modi as the state’s chief minister. For this neoliberal project, equality as the essence of self-rule was not important; only corporatization and the application of market logic in all domains mattered.

The “Gujarat model,” however, was politically underwritten by majoritarian unity, a mobilization of the Hindus as the bedrock of the polity.8 Accordingly, Modi has pursued neoliberalism while deploying Hindutva to manage the state–society relations convulsed by democratic mobilization. Since 2014, India has witnessed the Hindutva ideologues target dissent as “antinational.” In a different but also eerie replay of 1975, JNU students face the charge of subversion. Critics are dismissed as “rootless cosmopolitan” elites out of step with the supposed mass culture of Hindutva. This is to delegitimize criticism and win over those in the population not yet in their corner. It is the classic strategy of totalitarian propaganda to win over the insufficiently indoctrinated.9 Muslims have been lynched by cow-protection goon squads encouraged by restrictions on the sale of meat and the trade of cattle. The mob does not require any evidence for actual cow slaughter; it “knows” from totalitarian propaganda that a hidden conspiracy by Muslims is afoot to violate their reverence for cows.10 Supported by ground troops, which Indira’s Emergency rule never enjoyed, and a largely compliant and corporatised electronic media, which did not exist in 1975–77, the regime enjoys unprecedented power. It is equipped with the powers of the administrative state, including the law against sedition under the British-era Section 124A, preventive detention, and the Armed Forces Special Powers Act for use in the so-called “disturbed” areas.

What does this mean for democracy? The challenge posed by a growing surge of popular mobilization laced with ressentiment and the move toward authoritarian cultures and governments is not limited to India. Occurring around the world, these developments suggest a profound shift in the global experience of modernity and democracy. In India, this challenge arises against the previous background of a state of exception imposed by a powerful sovereign who deployed extraordinary constitutional powers and the resources of the administrative state to manage the population.

Today, there is no formal declaration of Emergency, no press censorship, no lawful suspension of the law. But the surge of Hindu nationalism has catapulted Narendra Modi into the kind of position that Indira occupied only with the Emergency. When she could not get the constitutional democracy to bend to her will, Indira chose to suppress it with the arms of the state. Today, the courts, the press, and political parties do not face repression. But they appear unable or unwilling to function as the gatekeepers of democracy in the face of state power spiked with Hindu populist ressentiment. Like Indira, Modi is his party’s undisputed leader. The Bharatiya Janata Party, which traditionally boasted a galaxy of seasoned politicians, now bows to its supreme leader. He looms as large in Indian politics as Indira once did. His photographs, slogans, and programs appear everywhere as hers once did. He does not hold press conferences and subject himself to questioning; he prefers to speak directly to the people with his weekly radio address and, like Donald Trump, frequent tweets. Without irony, Modi and the BJP leaders assail Indira’s accumulation of executive powers under the Emergency while they strive for a one-party state and display intolerance for minorities and disdain for dissent as “anti-national.”

With a powerful leader like Narendra Modi at the helm of Indian democracy, the last words belong to B. R. Ambedkar. Speaking at the concluding session of the Constituent Assembly on November 24, 1949, the Dalit lawmaker invoked John Stuart Mill to warn the citizens against placing their liberties at the feet of a great leader. Indians, he said, were particularly susceptible to bhakti, or devotion. This was fine in religion, but in politics, it is “a sure road to degradation and eventual dictatorship.”11

Notes:

1Dayal and Bose, For Reasons of State, 45.

2Selbourne, An Eye to India, 280.

3See the press release reproduced in Dayal and Bose, For Reasons of State,

appendix III, 215– 16.

4Statements by R. K. Ohri and Sushil Kumar, SCI, 31024/44/78- Coord- SCI,

NAI.

5Madhu Dandavate to Pramila Dandavate, December 6, 1976. Tis leter is part of the collection “Documentation of the Emergency Period in India,” Center for Research Libraries, Chicago, containing hundreds of leters and other documents. Te leters between the Dandavates are in rolls 2 and 3. All subsequent citations are from this collection and will only mention the date of correspondence. I am immensely grateful to Irawati Karnik for her translation of the leters and poems from Marathi into English.

6Madhu Dandavate to Pramila Dandavate, October 3, 1975. Te completed

book was published as Marx and Gandhi (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1977).

7Brown, Undoing the Demos, 41.

8Christophe Jaffrelot, “What ‘Gujarat Model’?— Growth without Development — and with Socio- Political Polarisation,” South Asia 38:4 (2015): 820– 38.

9Hannah Arendt pointed this out decades ago. See Te Origins of Totalitarianism, 342– 43.

10See ibid., 351, for Arendt’s insightful discussion of the mob and totalitarian propaganda.

11CAD, vol. 11, November 25, 1949.

Read more:

Disruptive Arrival of The Emergency