On 15 November, the Polish Institute organised the second edition of “Readings in the Shed”, an evening of poetry readings in New Delhi, the first edition of which was held in Mumbai. The reading was performed by acclaimed playwright, Ramakrishnan (Ramu) Ramanathan at the snug hall at Studio Safdar, and was composed of poetry from some of his favourite Krakow Poets.

One familiar with Ramanathan’s work will find that his art is situated in a dialogue – an extended conversation with artists who came before him, as well as his contemporaries. Be it through adaptations of Becketts’s plays or recreations of King Lear, or even collaborations with professionals and students from non-theatre backgrounds, Ramanathan’s work always engages with the life and imagination of artists, cultural narratives, and political discussions both Indian and global.

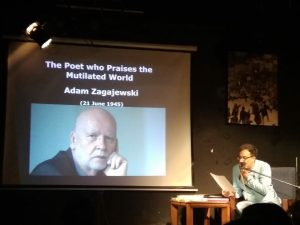

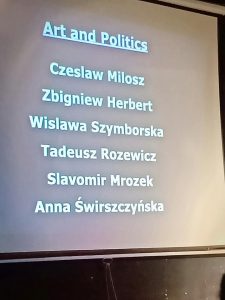

In his poetry reading session, he etched out intimate portraits of “some of his friends”, the Polish Poets, namely, Wislawa Szymborska, Zbigniew Herbert, Anna Swir, Czeslaw Milosz and Adam Zagajewski. He read verses they wrote, drawing with them, a kinship that was artistic but also historical and philosophical, throwing light on vital issues that have continued to play out in the domain of art and aesthetics.

Ramanathan has also produced a book of poetry. Published in 2016, My Encounters With a Peacock is a series of exchanges with a talking peacock. First published by the author in 2016, My Encounters With A Peacock is a series of enchanting exchanges with a talking peacock articulated in the form of short poems. These exchanges take place over the course of six months, from January to June, and constitute a total of sixty-five poems. Each poem is a conversation between the poet and the peacock, who are sometimes sharing a rickshaw, rarely eating akkhar masoor wali khichdi, often grieving about lost lovers, and always discussing bank interest rates like old pals. Adorned with just the right amount of delightful illustrations by Mansi Ghuwalewala and an intricate book design by Dibyajyoti Sarma, the 2017 edition of My Encounters With A Peacock makes for an enjoyable read. It also educates the human reader about living, breathing, talking unconventional peacocks, who challenge stereotypes by refusing to dance in the rain. Here’s a verse from the book

“Half a kilo of pure happiness

Can you home deliver that to me?

After all, I am the national bird of this unhappy country.

Since 1963.

You don’t want me flying

Across the border,

To Burma or Ceylon

As a mark of protest.”

– Ramu Ramanathan, My Encounters With A Peacock

Kanika Katyal of the Indian Cultural Forum had the pleasure of speaking to the playwright post the reading. Following is an excerpt from the interview.

Kanika Katyal: Why did you dedicate your “Readings in the Shed” session to Kedarnath Singh and Vishnu Khare?

Ramu Ramanathan: Both poets passed away this year. Kedarnath Singh is a true master. Three of his favourite Krakow poets were present that evening at Studio Safdar. Vishnu Khare was unwell when I last saw him for the Balshastri Jhambekar award program at Sane Guruji School in Dadar. I had to meet him in Mumbai a few days later. Unfortunately, that meeting did not happen. Again, one of the brightest minds I met. Their absence is a huge loss.

Today both of them will be with five of the poets: Czeslaw Milosz and Wislawa Szymborska and Zbigniew Herbert and Tadeusz Rozewicz and Slavomir Mrozek. Only Adam Zagajewski and I are alive.

KK: You told us that you had never been to Krakow or read the original works of the Krakow Poets in Polish, and yet you engaged with them intimately. I want to ask you,

a) How does a young reader in India in 2018 locate kinship with them?

b) Does this say something about translation as an enabler? Especially because you have prolific work on artists across languages, space and time, both as a theatre practitioner, as well as an editor of a print weekly.

RR: a). As I mentioned Marie Sklodowska-Curie never said to herself “I don’t know” … If she had, she probably would have wound up teaching chemistry at some private high school for young ladies from good families and would have ended her days performing this otherwise perfectly respectable job. But she kept on saying I don’t know, and these words led her, not just once but twice, to Stockholm, where restless, questing spirits are occasionally rewarded with the Nobel Prize. Poets, if they’re genuine, must also keep repeating, I don’t know.

b). The beauty is, as I mentioned during my reading session, the masters have translated each other’s poems. The same thing happened with playwriting in India in the sixties and seventies, when the masters (Tendulkar / Karnad / Mohan Rakesh) translated each other’s work. Likewise, the modernists who translated each other Ashok Shahane, Vasant Dahake, Dilip Chitre, Arun Kolatkar and Dhasal, etc.

KK: Let’s talk about this Marie Curie reference in a poetry reading. I found it a very interesting dialogue on the scientific temper in arts. Was it that?

RR: Yes, because immediately after that I quoted from M Holub, the immunologist. Also, most of the important theatrewallahs (from Kashinath Ghanekar to Dr Lagoo, from Mohan Agashe to Jabbar Patel, etc) in Pune / Mumbai are doctors. Likewise, some of the best theatre people I know in Mumbai were from BARC / TIFR!

KK: Then what makes a poetry reading different from a play from the audience’ point of view?

RR: Theatre needs an audience. That is the primacy of the spoken word. Sometimes, it is true with poetry. The two most popular poets in Hindi heartland are Kabir and Tulsi. People know their work through the spoken word.

KK: I’m reminded of what Belgian writer and critic, Luc Sante, said in an interview on discovering Rimbaud. He said, “That riff in “A Season in Hell” about liking idiotic paintings and reading outmoded literature and dreaming of unrecorded voyages of discovery and seeing carriages on the roads in the sky—that was virtually the template for my entire life! I could almost say that everything I’ve done has come from that poem.”

In your presentation, you showed us maps and talked about real and mythical cartographies. Could you reflect on living vicariously as a creative compulsion/commonality?

RR: I referred to Alberto Manguel’s The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. In it, Manguel takes us to … 1200 imaginary cities, islands, countries, and continents, from Homer to the late 1990s. … I tried to do the same with Krakow. Try to see the city through the poems. I don’t think I need to visit Krakow.

KK: You are seen as one of the voices of dissent in the theatre circuit. What is the importance of art in tough times?

RR: I recall what Ibsen said centuries ago in An Enemy of the People — The majority is never right. Never, I tell you! That’s one of these lies in society that no free and intelligent man can help rebelling against.

KK: What are the complexities behind the identity of an Indian writer writing in English about a diverse India? How do you negotiate the local, ‘Marathi tradition’ with the national, and the global? Can you tell us a little about your creative process as a writer?

RR: Language is a strange beast.

When Alberuni came to India, he accompanied Ghazni

He sought to learn Sanskrit

But the Brahmins said no

So he sat outside the temple

Among slippers and chappals

And mastered the language

Became the father of Indology.

Doing research has become a habit now. I’m not a historian or a scholar so to speak; I suppose I’m compensating for some deficiency from my student days. One of the plays that have just been completed is set around the time of World War I in India. While doing the primary phase of research that involves collating neutral information available about what transpired in Mumbai at the time, a few other aspects emerged. One was the question of Indian nationalism set in the time between 1850 and 1925, coming down all the way to the sort of ultra-nationalism one sees around the world today.

Around this time, there were about 7-8 political affiliations being formed in the city, interestingly in its southern tip. The RSS, the Hindu Mahasabha, Communist Party of India, the arrival of Gandhiji and Dr Ambedkar into the city — creating a sort of tussle for affiliation. This happened while unknown peasants and farmers were put on ships and sent off to Flanders to fight a war for the British that nobody understood. He says, “If you study that time, look through the speeches of some of these guys (some of whom were booked for sedition or were under the gaze of the British police), what emerged is that theatre was an adhesive to seemingly unrelated events in Mumbai. A lot of these plays were staged in South Mumbai, in the red-light areas… some of them were official, some other unofficial… I’ve spoken to two important scholars who have studied this time. These stories are so fascinating. All this is present in this longish and laborious play about the WW I in Mumbai.

KK: Please tell us about your future projects.

RR: [An] Idea for a play about Gandhiji. So, Barrister VV Oak attended the Nathuram Godse case in 1948. When the court was in session, Oak made sketches of the people in the courtroom. Also, he was a photographer who devised a way of enlarging a negative based on the principle of Camera Obscura. [An] Idea for a play about Dilip Ranade, ex-taxidermist at the CSMVS Museum in Mumbai. He stuffed animals during the day. At night, he read Kafka’s Trial and Castle. One day, Ranade created fibreglass sculptures of frogs, Edison’s electric bulb, Marilyn Monroe’s bra as a fossilised icon show.

Read More

How Game of Thrones inspired a children’s book set in Jharkhand

Sui Dhaaga: Weaving Deception