Image Courtesy: Harper Broadcast

Image Courtesy: Harper Broadcast

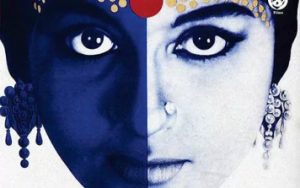

One of the tragedies of the oeuvre of Satyajit Ray cinema is that his film, Devi, has been often marginalised and side-tracked over his other masterpieces like Charulata and the Apu Trilogy. Devi (The Goddess), made in 1960, is a classic illustration of the influence of Kali and the superstitions that destroy the peace and harmony of a feudal Hindu family in Bengal. Based on a short story by Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyay (published in 1899 in the Bhadra (July-August) issue of Bharati, a Bengali monthly magazine), the film is Ray’s personal celluloid tirade against the superstitious mindset of the feudal Hindu Bengali that can stretch its beliefs far enough to ‘sacrifice’ an innocent young girl by deifying her as the Goddess Kali. The dictatorial feudal lord is represented through the character of Kalikinkar Roy, a deeply religious devotee of Kali. Kalikinkar, a rich landlord, is a widower, who lives in a palatial mansion in Chandipur, few miles away from Calcutta, with his two sons – Tarapada and Umaprasad, Harisundari, Tarapada’s wife and their little son, Khoka. Into this family, enters beautiful seventeen-year-old Dayamoyee, as Umaprasad’s wife.

Source: Jabberwock

Source: Jabberwock

One night, Kalikinkar envisions Daya as the incarnation of the Goddess Kali and proclaims her a goddess; and, thus, begins the iconisation of Devi. Kalikinkar goes so far as literally, placing Daya on a pedestal, where people came to offer prayers for the fulfilment of their wishes. When Umaprasad arrives from Calcutta (where he studies law), he is shocked to find the spectacle involving a dying child’s recovery at Daya’s feet that is seen as a miracle. The disbelieving Umaprasad tries to argue reason with his father and failing to convince him, plans to flee to Calcutta with Daya in the darkness of night. But Daya, now both intrigued and scared of her seemingly goddess-like powers, holds back at the last minute, and Umaprasad is forced to leave alone. When Khoka falls seriously ill, despite Harisundari’s pleas to call the doctor, Kalikinkar and the meek Tarapada insist that Daya would cure him. Harisundari is contemptuous in her distrust of Daya’s godliness, but helpless watching her son die in Daya’s lap. Umaprasad returns, determined to take his wife back with him, but Daya, shocked both by Khoka’s death and by her failure to save him, cannot cope with the schizophrenic dimensions of her life. She loses her sanity and disappears in the middle of tall blades of grass.

Kali’s representation in Bengali cinema is an inescapable reality. It is an extension of the omnipresence of Kali in the Bengali psyche on the one hand through her mythological form, and her cultural iconisation in myriad forms of art, music and literature.

Image Courtesy: Jabberwock

Image Courtesy: Jabberwock

A name that crops-up with reference to the metaphorical Kali on celluloid is Ritwik Ghatak. Ghatak’s women are eternal and infinite; drawn from mythology, and interwoven with a Marxist critique of the petty bourgeoisie, which dominated Calcutta, when he first set foot on it, after coming from Bangladesh. In this sense, his female characters are unique and Indian and also have within them the grains of the universal “Woman” by virtue of being eternal.

In Subarnarekha, the foundation for the transformation of Sita into the fiery Kali is laid early in the film. Sita, as a playful little girl, wandering about alone, is startled by the apparition of the Goddess Kali appearing out of the blue. For a moment, she is frightened out of her wits, but soon, learns that the frightening image of Kali is not real. It was a professional village folk artiste called Bahurupi in Bengali, who lives off by impersonating a God or Goddess or animal to entertain village crowds. Ghatak, explains that the intention of the Bahurupi was not to scare off the little girl. “She just came across him,” he said, adding, “I somehow feel that the entire human civilisation has just ‘come across’ the path of the archetypal image of this terrible mother.1

Ghatak’s ambivalent perception and critique of motherhood metamorphoses into a treatment that is thought-provoking. Basanti, Mungli, Malo and the other women in Titash Ekti Nadir Naam are fiery creatures, unlike the simpering, passive and helpless women of the average Indian film. They tower over the male characters in their humanism, their defiance of corruptive forces that arrive to uproot them, and their decisive and collective solidarity that brooks no rupture. When Basanti entices a landlord’s agent into a hut, a group of women bash him up for having made advances to Basanti. When the young, widowed mother of Ananta, the little boy, arrives at the village for refuge, unknown and anonymous among the villagers, the men look at her with suspicion. But the women rally around her and offer her support. Ghatak’s women are violent and fiery in different ways. They concur with the savage brutality with which Ghatak converts them into an idiom. They form the essence of his oeuvre. In Jukti, Takko Gappo, Ghatak, by design, reversed the practice in ritual performance theatre where men almost invariably play the public role of the goddess. Instead, he made the young woman in this film don the mask of Devi, as a mark of transgression.

Nabyendu Chatterjee, another noted filmmaker associated with non-mainstream Bengali cinema has used Kali prominently in two of his films. One of these, Ranur Pratham Bhag (1970-71), is based on a story by Bibhuti Bhushan Mukhopadhyay, portrayed in the film, from the perspective of an eight-year-old girl called Ranu. While walking along a street, one day, Ranu suddenly comes across a huge idol of Kali in a vast field, in a dilapidated condition. Apparently discarded by the neighbourhood post-institutional worship, she notices that the colour of the idol had peeled off, the clay had melted away, and the pupils in her eyes were missing. This idol of the Goddess, far removed from her pristine glory during a Kali pooja worship, still finds favour and faith in the eyes of the small girl, who kneels down before this discarded idol and offer prayers to cure the illness of her Mejka, her tutor, whom she is closely attached to. “As a human being, I do not believe in the existence of God. According to me, God is a fiction of man’s imagination. But from a director’s perspective, I wished to look at faith in Kali from the point of view of an innocent girl who is convinced that the Goddess in any form – old or new, beautiful or weather-beaten, has the power to cure her Mejka if her prayers are honest and spring from the heart,” explained Chatterjee.

If one were to take a closer look at the cinematographic realization of Devi, one will notice a slightly foggy/misty cover such as a mosquito net, in all scenes involving the husband-wife, endowing them with a dream-like quality. The misty veil in the intimate scenes between Uma and Dayamoyee is a beautiful reconstruction of the dreamlike, fragile quality of their short and sweet married life. The contrast to these surreal dreams is presented by the scenes showing the iconising of the bride as a ‘live’ Kali, emphasising it as the only ‘real’ thing in the film.

Devi has allusions of a Greek tragedy in which Kali, the destroyer, exacts her necessary sacrifice – through Khoka, through the death of Daya, and through the destruction of the Roy family, perhaps as a ‘punishment’ meted out to an ardent devotee who dares a mortal to take her place as Goddess. On another level, Devi unfolds as a study of the subconscious forces that hold a family together. Kalikinkar believes that his daughter-in-law is the Goddess Kali because he misinterprets a dream, yet, he is no villain. He acts in the only way he is expected to, as a man of his time – dictatorial, feudal and so rigid in his beliefs that he sees a dream as a sign from the Goddess, and in his quest to bestow upon it a real, concrete form, turns the little bride into Goddess incarnate, lining up crowds seeking her benevolence and blessings.

Source: Filmsufi

Source: Filmsufi

Ray’s film reportedly differs and departs from Mukherjee’s story in several respects. In the Mukherjee story, the plot concludes with a demure sixteen-year-old hanging herself, as she would much rather die than face the humiliation of being a failed healer, a false Devi. In Ray’s rendition, the character of Daya loses her mind; she runs across a field near the family’s mansion and vanishes into the mist. The last shot of the film, repeating the first, shows the unadorned white clay face of the idol of the Goddess, an image shorn of the colours and attributes humans usually ascribe to her.

Devi is a classic tale of an ordinary girl becoming an icon, a Goddess under the whims of an elderly man. This conversion of a subject into an object of veneration, beauty, devotion and blind faith, through entrapment, is unique in Indian cinema.

Dayamoyee was content in her husband’s open fondness for his teenaged wife. Before leaving for Kolkata, we see Umaprasad leaving fifty white envelopes, addressed to him in English in his beautiful slanted hand, for Doya to write to him “every day”, each one for his day of absence. But the envelopes remain unused as Doya gets entrapped in her Goddess avatar with her father-in-law monitoring her every waking minute. In a moving scene, we see Doya, while still in her Goddess mode, trying to fetch one of these envelopes to write to her husband about her tragedy, asking him to rescue her; but when he finally comes, it is too late. The addressed ‘envelopes’ that mark the adoring love of a husband for his wife becomes an exercise in futility by the machinations of a third man – the husband’s father.

Daya rarely speaks after she is forced into the Goddess mode. Her steadily drooping shoulders, tired helpless eyes, silent tears streaking down her cheeks, and her submission of the shift from her bedroom to a room downstairs, speak volumes about her pathetic state.

Khoka, once closely attached to his aunt, is now scared of stepping into her shadow. In one scene, while he is at play, his ball rolls into the room Daya is resting in. Daya waves at him to come in. He quickly runs in, picks up the ball and runs out without speaking to her. The soft smile on her face disappears. Though the ball, a plaything, that once served as a bridge between a child and an adolescent woman, remains today, yet the playmate is no longer the same.

Devi throws up a different facet of womanhood in a Bengal we are not familiar with except through literature. We accuse society and corporate interests such as the advertising world of objectifying the woman as a commodity in order to push sales of goods they may or may not be linked to. But in Devi, we discover the eldest patriarch of a family satisfying his own ‘devotional’ interests by ‘reducing’ his daughter-in-law into an animated, live version of his favourite Goddess Kali and vesting her with ‘magic powers’ she does not possess because she is a woman. There is a long, single shot in Devi through which the viewer is offered an insight into the protagonist, Dayamoyee’s aborted rebellion against the goddess-image she is vested with, much against her will. On the morning after she appears to him as the Goddess Kali incarnate, when her father-in-law, Kalikinkar Roy bends to touch her feet, Dayamoyee, curls her toes inwards, scratching her nails down its length, and turns to the wall. The expression on her face, seen through partial-profile, registers a strange, almost uncanny blend of anguish, self-pity, pain, grief and surprise.

1. Ritwik Ghatak: Chalachitra Chinta in Chitrabikshan (Bengali), Special Issue on Ritwik Ghatak, January-April, 1976, Calcutta, p.53.

Read more

The Muslim in Hindi Cinema

Notes on Rangini and other monologues by women