On my visit to West Bengal, I went to see Tagore’s dream child, Shantiniketan and his residence at Calcutta – Jorasanko. Jorasanko houses a host of Tagore’s childhood photographs and books. Tagore’s room and the spot where he breathed his last have been meticulously maintained. In fact, you move around the house with the melodious, ‘Rabindra Sangeeth’ in the background! While strolling past Tagore’s archives, my mind moved to Kannada poet, Kuvempu’s house in Kuppalli, which has been modelled on similar lines to bring the memories of the poet laureate to life. Structurally, Jorasanko, looms like a palace when compared to the Kuppalli house. The Kuppalli house occupies a corner of a coffee estate where the song of the cuckoo and drongo can still be heard. Jorasanko, on the other hand, is on a busy street that bursts at the seams with people. The age-old trams roll right in front of Jorasanko as cycle rikshaws pass-you-by on the street. I spotted a barber on the pavement with his box of blades and scissors and a host of men waiting for their turn. I wondered if it was this surrounding that lent a touch of reality to the life of an otherwise princely poet! Tagore denounced the aristocracy, which he saw as an impediment to receiving ‘real-life’ experience, to live in villages and learn from the lived realities of ordinary people. Correspondingly, the poet, Kuvempu, though born in a village, moved to the city to let the urban modernity and rationality shape his personality. It’s a marvel how pastoral experience and the intellectuality of cities coalesced to shape the writers of modern India!

Though the historical realities that shaped Tagore and Kuvempu are different, yet, the similarity between these two writers is striking. Both artists hailed from a feudal background but advocated for the rights of the downtrodden. Both were philosophers, sharp intellectuals and humanists, who called the youth to break free. In fact, Kuvempu’s, idea of ‘nirankushamati’ meaning, ‘free-spirited’ reads like as an extension of Tagore’s ‘Prayer’ – where the mind is without fear’. Both poets influenced the masses with their writings and personality to emerge as cultural leaders. Their writings transcended the self, to contribute to nation building. For instance, Kuvempu’s, ‘ JayaBharata Jananiya Tanujate’ became the state song while Tagore’s ‘Jana Gana Mana’ acquired the status of the National anthem. Both poets wrote in their native language, which gave a local flavour to their poetic expression. Both welcomed modernity and the Western model of education as liberating and also started education centres. Both leaders held Gandhi in high-esteem but had differences with his nationalist movement agenda. Both were connected with the contemporary Irish poets – James H Cousins, the Irish poet, encouraged Kuvempu to write in Kannada, while W.B Yeats wrote the foreword to Tagore’s Geetanjali.

Despite the similarities in their artistic and cultural pursuits, both poets came from very different socio-economic backgrounds. Tagore who was born in a Brahmin household did not face the social challenges that Kuvempu did, which went on to inform his creative and intellectual endeavours. This is evident from the fact that, while Tagore drew extensively from classical and folk traditions, Kuvempu’s work does not draw resonances from the rich folk traditions of Kannada land. This points to the historical access to classical literature that the upper-caste brahminical writers enjoyed, which enhanced their abilities to enrich the literary world. As a result, the non-brahmin writers, who were familiar with folk narratives, moved away from them to classical traditions! This feature of their writing reveals an interesting paradox of the artist’s intent, that of a yearning for the other, and demands for the creation of a new paradigm of reading them! For instance, Alooru did not consider the folk art and people as central to his thought; Kuvempu, opted for the classical tradition of literature; while Tagore, through his work, empathised with the folk and the marginalized. Tagore’s Bride and Gora are examples of his rich inclusive worldview. Kuvempu, on the one hand, like Rumi, sang that the land should become the garden of peace, but his works like Bheema of Hampi or Not Christian but the daughter of Priest make for a problematic reading when seen under the same lens. I wonder how richer Kuvempu’s work could have become had he drawn from folk epics like Manteswamy and Mahadeswara. In such a context then, it would be helpful to ask – Where do we place writers like Girish Karnad, Ananthamurthy, Kambara, Devanooru Mahadeva, and Tejaswi?

Coming back, Tagore was multi-talented. He was adept in music and painting. His experiments with colour are astonishing! Being blessed with the opportunities to travel around the world, Tagore, harnessed his experiences into his work. The philosopher in him saw travel as the way to knowing the world. He shared this view with Gandhi, but it was the differences in their respective approaches which made them see two different India(s). In 1882, Tagore came to Karwar(in present Karnataka) to visit his brother Satyendranath who worked as a judge but ended up falling in love with the sea. He dedicates a chapter in his autobiography to this experience. The shore of Karwar still bears his name.

Like Tagore, Kuvempu also adored nature, therefore, when Kempu visited Calcutta in 1929 to receive the deeksha at the Ramakrishna Matha, he was appalled by Calcutta’s filth. The city that displayed life in its many forms to Tagore, seemed like nothing but dirt and filth to him! I wonder what a meeting between these two literary titans would have been like had he met Tagore! I, do, however, strongly believe that Calcutta did play a decisive role in shaping Kuvempu’s thought process. He was more influenced by ascetics like Rama Krishna Paramahamsa and Swamy Vivekananda than by Bankimchandra Chatterjee or Tagore. Yet, Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana inspired his Jaya He Karnataka Mate. Even the characters of Ramayana Darshanam were shaped on the lines of Tagore’s ‘Disrespect to Poetry’. Kuvempu had read Tagore in his childhood and had also attempted to translate his poetry. In school, too, Kuvempu’s was lovingly called ‘little Ravindra’ by his teachers. But when Kuvempu read Geetanjali he felt that Kannada literature had better experiments in form and content and even found some of his own writings far better than Geetanjali. This shows Kuvempu’s confidence in himself and his craft. Indeed, it cannot be denied that in terms of depth of creativity, Kuvempu looms over Tagore.

Both Tagore and Kuvempu were not only famous for their writing but also their intellectual rigour. Both critically engaged in interrogating the power-centres of the time. For instance, Tagore returned his Knighthood in protest against the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy. Kuvempu, too, though initially wrote poems eulogizing the kings of Mysore but later stood up to the Royal authority. Ironically, the same two writers who opposed the state found public sanction and were considered cultural icons of the land by the same rulers. Tagore has captured the cultural identity of Bengalis so powerfully that one can find his poems even, on walls of Calcutta tram stations! The middle-class milieu of Calcutta is hooked-on to Rabindra Sangeet. In Karnataka, too, we have roads and layouts named after Kuvempu. But Kuvempu hasn’t seeped into our cultural consciousness the way Tagore has for the Bengalis. Though Kuvempu’s ‘Jayabharata Jananiya Tanujate’ is sung compulsorily in schools it seems like mere lip service to the poet. This is because, when a crucial thought process is reduced to the level of quotation in speeches, or when a great poem is turned into compulsory parrot reading, its core meaning is lost. I wonder if this dilution of meaning also happens in the case of the national anthems when melody takes precedence over meaning.

It is different when poet philosophers turn into memorials and their ideas become a part of the collective consciousness, however, it is better when a humanist writer becomes an icon of a land’s cultural identity; and assumes the task of rewriting history. It is an important undertaking because history has often portrayed violence as valour – as in the case of Shivaji. Just as Calcutta has the Ravindra Sadana, and the Ravindra Road etc., Mumbai is full of parks, statues, and airports that bear Shivaji’s name. Every time, the Shiva Sainiks chase and beat up the migrants making a living in Mumbai, the problem of a pre-modern warrior king becoming the symbol of in post-modern times looms large. Yet we can’t forget that like Bengal, Maharashtra, too, has given birth to humanists. In fact, compared to the Bengali linguistic parochialism practised in Calcutta, Mumbai, even today, remains a multicultural and multilinguistic cosmopolitan city owing to the many historical and linguistic factors involved.

Karnataka houses a large literary public of Tagore’s writings, including translations and criticism. As a result, the Rabindra Kalakshetra in Bangalore hosts many Kannada programs. In Calcutta, however, even the major writers are unaware of Kuvempu, let alone the common man. While the Bengalis systematically made Tagore a national bard, many a poet like Kuvempu and Bendre paid the price for writing in regional languages and remained islands at the regional level. This cultural crisis points to the politics of translation.

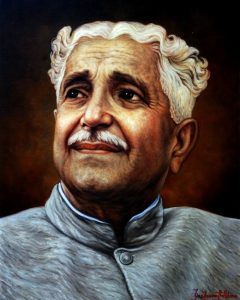

I wanted to take with me, a memorabilia from Shantiniketan, so I bought a photograph of Tagore. There were two photographs of Tagore – one of a handsome young man with an aquiline nose and expressive large eyes; and another, the often-seen picture of Tagore in a long, flowing gown with a grey beard and flowing grey hair. I preferred the young Tagore.

Both Tagore and Kuvempu hailed from well to do families, who aimed to nurture the minds of their homeland through their thoughts, writings and activism. To this aim, they empathized with the most marginalized characters in their works – as Tolstoy did.

Strangely enough, every time the name Tagore is mentioned before me, my mind doesn’t jump to ‘Jana Gana Mana’, instead, the portrayal of Anandamayee as the mother in Gora and the character of the raisin trader who waits to see little Minni becoming a bride in Kabuliwala flash before my mind. Similarly, with the mention of Kuvempu, I don’t automatically remember his, ‘JayaBharata Jananiya Tanujate’, but his portrayal of ‘Naayigutti’ and his wife Timmi in Malegalalli Madumagalu.

While, the houses at Jorasanko and Kuppalli do enliven certain memories, but a writer truly lives within us, through his creations; his enlightening thoughts; his moral actions and so on. Rulers can confer many a title on the poets and writers, but, it is only by residing in the memory of the readers that they become immortal.

Rahamath Tarikere is a Professor at the Kannada University in Hampi and a Sahitya Akademi Award-winning writer. He returned his Sahitya Akademi Award to protest against the killings of scholar M M Kalburgi and rationalists Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare.

Dr Shakira Jabeen is from the Department of English, Nehru Memorial College, Sullia, Karnataka.

Read more:

Perils of an Imagined Enemy,

Beyond the Confines of Religion: A Look at Karnataka’s Syncretic Legacy Through the Celebration of Rajappa Swami’s Urus,

The Bond between Language and Script