There are three operative words in the title of this piece – “Muslim”, “Hindi” and “Identity” as if these are mutually exclusive terms that need to be brought under a single umbrella. Why? Would anyone think of naming an article “The Hindu in Hindi Cinema?” or, “The Parsee in Indian Cinema”? Because the mainstream identity of most characters in Hindi films represent the Hindu majority. While very few films centered on Parsees find place in the history of Hindi cinema before the term “Bollywood” became infra-dig. Then why pick on the Muslim representation in Hindi cinema as if it needs special focus?

The answer is simple – the Muslim identity and its representation, especially within the matrix of modernisation within India has changed our perspective towards the Muslims, more often prejudiced against than for and this reflects itself through the creations of filmmakers. Add to this the volatile environment of the currently politically constructed “communal” conflicts that do not really exist and yet are reiterated everyday by a gossip hungry, maliciously greedy media often disguised as “objective and neutral reporting.”

Aristotle said, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” In other words, when individual parts are connected together to form one entity, they are worth more than if the parts were in silos. Let us try to apply this to Mulk, the recent film running in Indian theatres right now. Directed by Anubhav Sinha, the film narrates a story centered on a Muslim family living with feelings of brotherhood with their Hindu neighbours. But was all that bonhomie for long years just a mask that revealed the ugly face of suspicion when Maulana Murad Ali’s (Rishi Kapoor’s) nephew (Prateek Babbar) is caught as a dreaded terrorist? The nephew, accused of bombing a bus that killed innocents, is trapped in his own house till the upright police officer Danish Javed (Rajat Kapoor), also Muslim, shoots him down. Was this an encounter killing that may never have happened if the officer had not been prejudiced against his own?

The entire family including the father of the terrorist, Murad Ali’s younger brother Bilaal (Manoj Pahwa) is interrogated so ruthlessly for days on end that, with a heart problem, he dies while being taken to hospital. His wife and daughter are brought in for questioning while Maulana is arrested for being complicit with his nephew in terrorist activities. He persuades his Hindu daughter-in-law Aarti Mohammed (Taapsee Pannu) to plead in his defence because though he is a lawyer himself, it would be impossible for him to prove in court that he really loves his motherland (India) and will never ever go away to Pakistan, a sign chalked outside the wall of his ancestral home.

It is a beautiful film whose main agenda is to underscore the constant shadow of suspicion Muslims, old and new, who chose to stay back in India when the Partition took place must live in never mind how much in harmony they have lived through generations with love and a sense of deep belonging.

But take a closer look and you discover that Mulk is a very cleverly made mainstream film with the usual clichés the box office demands. There is a group song-dance number performed at the birthday of Murad Ali Mohammed where he himself has taken charge of cooking the biryani and the kebabs with some romantic teasing with his wife Tabassum (Neena Gupta). Sinha also brings in a Hindu daughter-in-law who is a qualified lawyer that subtly underscores Murad Ali’s secular beliefs. There are dynamic action scenes with the chasing of the young terrorist, the public bus bursting into flames, the police doing a combing operation in Murad Ali’s residence ending with the young man being shot down. The police interrogation of Bilal Ali underscores how the police force is prejudiced against anyone who has the label “Muslim” written on his forehead. The prosecution lawyer, Santosh Anand (Ashutosh Rana) does not make any pretence to hide his terrible hatred for Muslims and the entire court, filled with Hindus, giggles at his extremely derogatory jokes around Muslims.

Murad Ali is absolved of his crime and his long-time Hindu friends approach him with sheepish faces but he keeps his distance. There are songs too, and one really good one on the soundtrack. These are the cinematic clichés not to talk of the technical excellence and the outstanding performances of all the actors including the underrated Kumud Mishra as the balanced Hindu judge.

The point one is trying to make here is that all these commercial clichés may appear clichéd when taken separately but, taken together as a symbiotic whole, Mulk comes across as a very powerful political statement on the increasing lack of secularism that had evolved into virtual hatred for the Muslims that has bestowed on Muslims the rather dubious shadow of bearing a “terrorist” identity.

There is a very politically constructed and intentionally designed cliché in the casting itself. Every member of the acting cast is Hindu in real life. Explaining why he designed this to be so, Sinha said that if he had taken Muslims to play any role in this film, it would have “infected” the point he was trying to make. What does “infected” mean in this context? Sounds quite ambiguous to this writer.

Gone are the days when the Muslim identity in Hindi cinema celebrated the Muslim ethos with the dignity it deserved. Late Iqbal Masud in his seminal article Muslim Ethos in Hindi Cinema extolled the virtues of filmmakers like Sohrab Modi, Guru Dutt and Shyam Benegal who, though non-Muslims, could have staked their claim over the representation of the Muslim ethos in Hindi cinema. Manmohan Desai, who was partly responsible for the creation of the celluloid image of Amitabh Bachchan, went on record to state that if Muslims did not like a film, it flopped.

Dr. Seemin Hasan in her paper, Locating the Muslim Identity in Popular Indian Cinema (November 10, 2012) writes: “The Muslim community of post-partition India occupies an in-between space beyond the self and before the other.” This may have had some truth in it way back in 2012, but today, the Muslim may not be dressed or behave or speak like he/she did in earlier Muslim Socials such as Mere Mehboob or Chaudhvin Ka Chaand or Pakeezah, the celluloid Muslim is quite definitely “the other”. In fact the evolution in the mutations that have happened in the representation of the Muslim in Hindi cinema has been one of discontinuities, non-linear and non-evolutionary.

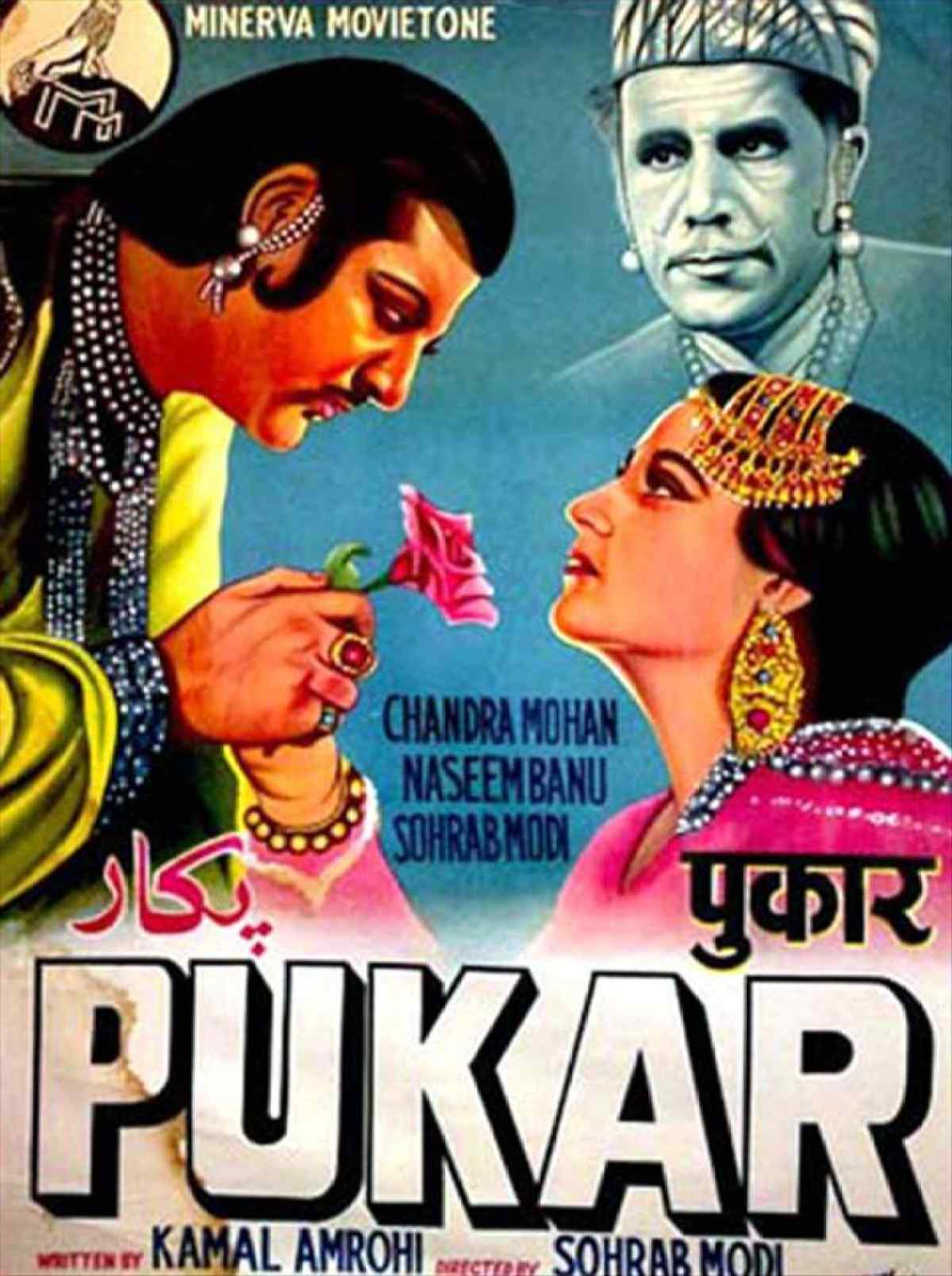

The strong presence of the Muslim, man or woman in Hindi cinema can be traced back to the 1920s when a then-homogenous Indian audience thoroughly enjoyed fictionalised “historical” romances like Anarkali (1928), Noorjehan (1923), followed by Sohrab Modi’s thumping hit Pukar (1939). With the 1940s came Humayun (1945) followed by Mumtaz Mahal (1952) and the great blockbuster Anarkali directed by Nandlal Jaswantlal. They were richly mounted, period costume dramas with scintillating songs and music and loud melodramatic acting which the audience loved and the thought of being overly representative of the minority community did not occur even once.

Alongside were mainstream films with modern storylines that featured a Muslim man or woman in an interesting cameo one film after another. One of the best examples is B.R. Chopra’s Dhool Ka Phool (1959) where we find a Muslim fakir bringing up a little infant whose religion he does not know and sings, tu Hindu banega na Mussalman banega, insaan ki aulad hai insaan banega. The illegitimate child abandoned by his mother for fear of social ostracism, turns out to be Hindu by birth and this film is one of the first mainstream films in Hindi to strongly recognise the secular identity of an Indian.

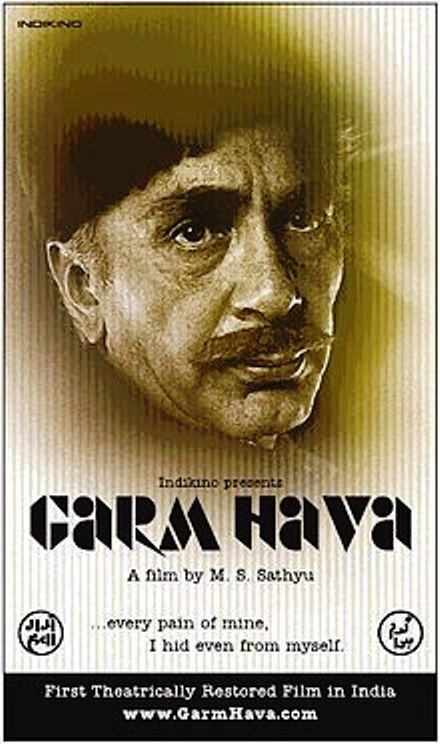

On the other hand, one also saw the Muslim identity in courtesan-centric films like Pakeezah, Benazir and Umrao Jaan that reflected yet another image of Muslim aristocracy and feudal lifestyles. They belonged to typical romance sometimes ending in tragedy. Stories that brought out the pathos of Partition among common Muslim families such as M.S. Sathyu’s Garm Hawa and Shyam Benegal’s Mammo were mere drops in the ocean that catered to a niche audience. Mahesh Bhatt’s Janam was a different cup of tea that presented a very good though a crassly commercial account of the victimisation of a Muslim and his dead mother during the communal riots in Mumbai. Many years later, who would have dreamt that the imaginative Vishal Bharadwaj would be inspired by William Shakespeare’s Hamlet preceded by Macbeth to make two Muslim-centric films like Haider and Maqbool, where Haider is placed very topically within the unrest in Kashmir with the drama tilted in favour of the mother who, unlike in the original, is martyred by Bharadwaj?

The picture is different today. It is as if the average Muslim is trapped in the identity of a terrorist or a mafia goon or a professional killer, almost without exception. A bit of ‘lip service’ is paid by putting in a few Hindu members of terrorist or mafia groups but one understands the psychology – it is ‘lip service’ for fear of reprisals on grounds of communal partisanism to the majority community. The Central Board of Film Certification has sometimes put its foot firmly down in having scenes deleted from some films for fear of hurting the sensibilities of the minority community. Mani Ratnam’s Bombay is a case in point. Ravi Vasudevan in Bombay and its Public (Journal of Arts & Ideas, No. 29, January 1996) opines that the CBFC’s insistence on deletions of the given scenes was prompted by the censor board’s anxiety that they would lead to a re-kindling of anti-government sentiment among Muslims many of who assumed that the demolition of the Babri Masjid was a failure of the government to represent their interests.

From the mafia, gangster, terrorist, goon and professional killer at home, reflected in umpteen films from Company to Once Upon a Time in Mumbai to Nishikanth Kamath’s Mumbai Meri Jaan to Amir and A Wednesday, the Muslim suspected as terrorist is now neatly placed on foreign soil such as in the US, UK, Istanbul, Kabul, London and Pakistan. What necessitated this geographical/cultural/political shift to a different country? Are the producers afraid of the CBFC clamping a ban on their films? Or, is it because it is easier to get dates of top stars and shoot a film in a single schedule entirely on foreign soil? Or, are the powers-that-be behind these films scared of communal reprisals at home from both the majority and minority communities?

Shahrukh Khan’s My Name is Khan was shot entirely on American soil. No one even listens to his complete sentence when he says, “My name is Khan and I am not a terrorist” and pounces on him by presuming precisely the opposite. “My Name is Khan is a mirroring of the times, of wounds deep and fresh, through the eyes of a man whose autism – Khan has Asperger Syndrome, a high-function variety – makes him take things as they are without bitterness or sarcasm,” film critic Pratim D. Gupta points out.

Mulk is an excellent example of how a single film can at least make a sincere and honest attempt to dispel the long-held belief among the majority that Islam and terrorism go together and that, mainly after 9/11, the two are inseparably mingled. The main thesis is to state:

- That if one member of a Muslim family turns out to be a terrorist it does not automatically ghettoise his entire family, women included, as terrorists.

- That the identity of a Muslim like any Hindu or Christian or Parsee or Sikh, is inseparably integrated into his/her national identity and not communal identity.

- That it is not necessary to turn the term “identity” on its head and try to tag the Indian Muslim as one whose religion matters more than his/her country which is a prejudiced perspective on all Muslims.

At one point during her argument, Aarti sharply points out that Indian Muslims like Murad Ali chose his nation over his religion during the 1947 riots and the Hindu friends who rescued him during the 1947 riots turn against him the very minute his son is declared a terrorist. During the court questioning, where his defence lawyer who is also his daughter-in-law, adopts the strategy of a prosecution attorney, questions the court why systemic violence against adivasis and Dalits by upper caste Hindus is not considered as acts of terrorism. Murad Ali adds his own logic by asking why violence during the anti-Sikh riots in 1984, the progrom in Gujarat in 2002 and the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992 are not considered acts of terrorism.

According to Syed Ali Mujtaba, Muslim characters generally get a raw deal in Hindi films. They are depicted as smugglers, rowdy history sheeters dressed in lungis and sleeveless singlets that run counter to the general appearance of an average Muslim in Indian society. He says that the characterisation of most Muslim women as tawaifs and nautch girls with Muslim names twists the image of the Muslim woman. Words like “Pakistan”, “Kashmir” and “The Taliban” are no longer identified with countries or states or reactionary militant groups but as symbols of evil so far as Bollywood cinema is concerned. “Kashmiri militants are shown as gun totting bearded guys wearing skullcaps fighting the Indian security forces. Kashmiri militant’s linkages move in a linear direction to identify with Pakistan and Talibans. Characters dressed in Afghan outfits with a scarf over the shoulder are shown mouthing some Arabic words, scheming to launch Jehad against India,” says Mujtaba.

Will films like Mulk make at least a dent in this school of representation and reception of the warped, twisted and distorted definitions of the Muslim identity in Indian cinema?