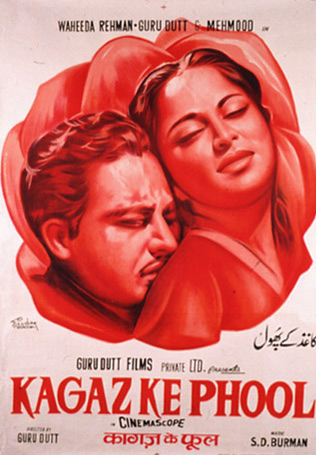

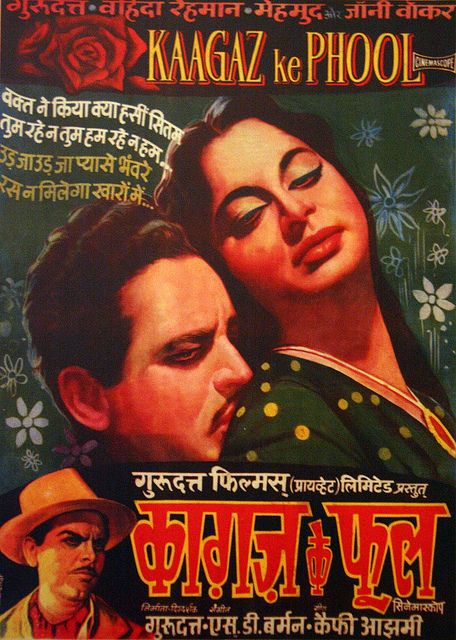

Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) is one of the most moving self-reflexive films made in India. It is a fine and subtle tribute to the glorious days of the studio era, using its history from about the 1930s to the 1940s as its backdrop. An early shot in the film reveals Suresh leaning from the balcony of a cinema hall where Vidyapati, a film of 1937, an unforgettable musical romance with Pahari Sanyal and Kanan Debi enacting the classic lovers, playing to a full house. The films that Suresh is shown making or having made in the film are films that actually exist in the archives of Indian cinema. 9th July was Guru Dutt’s 92nd birthday. This gives us the platform to discuss his biggest flop and his pet film for film scholars and critics across the map – Kaagaz Ke Phool. 2018 also marks the 59th anniversary of the film.

The film is an introspective and retrospective journey of Suresh, a once-celebrated film director who is currently going through a bad patch both professionally and personally. He is estranged from his wife and daughter, while Shanti, the leading lady who he had groomed to fame and glory, and had subsequently fallen in love with, has drifted away. He discovers that the studio floors are his last recourse, and seeks refuge there, tracing back his journey. He finally comes to terms with the reality that fame and success are as ephemeral as life itself. By then, however, it is too late to travel back in time and remedy things.

Kaagaz Ke Phool focusses primarily on Suresh Sinha, a director of films. Three women of different ages and from different backgrounds mark his life. One of them is his wife Bina (Veena), another is his growing daughter Pammi (Naaz) and the third is Shanti (Waheeda Rehman), the woman he introduced to films and who later became a famous star. Suresh is estranged from Bina when the film opens. His rights to visit his daughter at boarding school are also withdrawn. Later, Suresh meets Shanti, an orphan, and by a strange twist of fate, introduces her to films. They fall in love but never get to express their love for each other. When Pammi learns about the ‘affair’ through the gossip glossies, she persuades Shanti to leave her father alone and tries to reunite her estranged parents, but in vain. Shanti goes away and Suresh finds himself sucked into a loneliness and alienation of his own making.

The three women play three different roles in his life. The wife and the daughter affect him negatively even with their physical absence from his life. It is Shanti who functions as the sacrificing woman who falls desperately in love with him but fails to rescue him from a tragic death. Suresh is in love with Shanti the actress and not Shanti the woman. Taking his relationships with the two other women in his life, can one conclude that having lived within the synthetic world of make-believe; he is incapable of loving a normal woman any more? Does he love Shanti as an actress because it allows him to command her life, to control her actions in any which way he desires? Even with these manipulations, he sticks to the characters she plays in his films rather than to Shanti as a woman per se. As Darius Cooper, in his book In Black and White – Hollywood and the Melodrama of Guru Dutt, rightly comments: “When Shanti wants to step out of her characters and approach Suresh as a woman, she interferes not only with the process of sublimation but also disturbs the process of identification. Hence his need to avoid any physical contact with her.” Her need to touch him in some way is conveyed by what later evolves into a manic obsession for knitting sweaters that he will never wear. Yet, she hopes to embrace him vicariously if only in wool.

The most telling metaphor in Kaagaz Ke Phool is Shanti knitting sweaters It is introduced as an innocent time-filler when she begins knitting on the sets during breaks in the shooting. Later, when Pammi’s insults force her to retreat into the village and turns her into a recluse, away from films and the fame that comes with it, Shanti presents Suresh with a sweater, the only one she could manage to give him. Years later, during the shooting of a film, as the female lead, in a scene she is supposed to do with a bit player, Shanti recognises Suresh who steps in as the bit player from the sweater he is wearing when he removes his costume. It is full of holes now, but he still wears it, almost like a second skin. We last see Shanti as a doomed Penelope figure obsessively knitting sweaters for her Odysseus who will never return to claim them or exchange them for the one with the holes. Her cupboard is spilling over with sweaters. But now, it is no longer an innocent exercise to kill time. It is an obsessive act indulged in by a woman who is insanely in love with a man who is both afraid and incapable of loving her in return. It is an act of hope too. It is an escape route for a woman who is aware of the futility of her act. She is like the proverbial ‘dying man clutching at a straw’ that cannot and will not save her in the end. Nasreen Munn Kabir writes in Guru Dutt – A Life in Cinema: “A dying woman knits them for a man who refuses to die in her memory.”

Shanti’s life, after she comes in contact with Suresh, is defined by intermittent phases of waiting. The first time she appears in the frame, one finds her waiting under a tree in a park to save herself from getting wet in a sudden burst of rain. As an actress, she spends a lot of time waiting on the sets as the lighting and props are being prepared for the next shot. She arrives in the studio much ahead of the others and waits in the dark studio to profess his love for her. It never happens. When Suresh has an accident, Shanti keeps awake all night by his side, waiting for him to regain consciousness. But instead of being thanked for this, Suresh asks her to leave the minute he regains consciousness. Maddened by Suresh’s dogged refusal to acknowledge their mutual love and need, she takes refuge in her bedroom, strewn with a hundred sweaters, “knitting for a man who will never wear them. She is condemned to continue waiting.”

The first thing that strikes one about the women characters in the films of Guru Dutt, taken separately or together, in terms of an individual film or looked at holistically, is that almost all of them are scripted and given shape to evoke the sympathy of the audience. The second quality is that they have great resources of inner strength that they draw upon as and when the situation arises, not caring about the impact of such decisions on their own lives and destiny. Thirdly, the women are almost totally focused on love above everything else. It is love that makes their world go round, sometimes working in their favour, mostly working against them, occasionally leading to either destruction or death. Their patience in love is another positive quality. Finally, except in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, they are subsidiary to the protagonist, always a man. According to Laura Mulvey, who is cited in Griselda Pollock’s essay “Report in the Weekend School”, the women’s point of view does not dominate.

Kaagaz Ke Phool was India’s first cinemascope film with brilliant cinematography by V K Murthy. The cinematographer had multiple responsibilities. One, he had to shoot the film as the audience would see it. Two, he had to shoot the ‘indoor studio sets’ where Suresh shot his films with the right touch of light and shade and chiaroscuro it needed to reflect the periodtime-setting of filmmaking the film represented – approximately the years between 1930 and -1940. Three, he had to maintain clear lines of division between the surface film to create the holistic effect it needed, and the make-believe structure of the studio-within-the-film. Four, he had to present the simulated indoor studio ‘sets’ to portray two different moods – the mood of success with bright lights and busy technicians, director, actors, in the earlier scenes, and the mood of failure when Suresh, sad, alone, an enlarged figure of tragedy and failure personified, steps into the studio again as the film, very slowly, almost regretfully, moves towards its inevitable tragic climax. The tragedy is like a paean to filmmaking as an ephemeral phase in the life of its creator, the filmmaker, the films-within-the-film and the larger film itself.

Interestingly, Dutt weaves his film-within-a-film story with Devdas, which is the film being directed by Suresh. He manages to persuade his producer to cast Shanti, an orphan girl he had met in a park one day to play Parvati in the film. The entire sub-text happens in a series of coincidences and accidents. Not once does one get to see Devdas actually being shot in this film. But there is this strong sense of intercutting between Devdas and Suresh with Suresh taking to the bottle and losing out on life, family, and love. Towards the end of the film, the only retreat for Suresh is the studio where he shot many successful films. Here, with his cameras, his arc lamps, his backdrops, his sets, his technicians and his actors, he can create and control his own world of make-believe and beauty. But the space grants him only the metaphorical consolations of a fictive universe. When he loses his favourite actress in this space, and his daughter in the courtroom, he begins to drink, as if with a vengeance, and becomes homeless. He returns to the space all over again after having lost his family, his career and his audience. By now, Cooper says, he defines the space as an indoor space that has evolved into a private sepulchre for himself.

Kaagaz Ke Phool has strong autobiographical elements structured into it. It is almost like a celluloid elegy Dutt wrote for himself with his screenplay and his images, his music and his lyrical pacing of the film. He is said to have had an intense relationship with one of his leading ladies, as shown in the film. He was the one who introduced the lady to the world of cinema. This brought about phases of estrangement with his wife Geeta Dutt and their children from time to time. He began to indulge in drinking during periods when he was not working. He suffered from long periods of depression. And he continued to be a chronic insomniac. It is said that his premature death by suicide was foreshadowed in the film. The film was a failure in every sense of the term. In some cities, the film ran for only a week. Only years later did it receive the acclaim it deserved and now it enjoys a cult following in India and other countries such as France where it was commercially released in the 1980s.