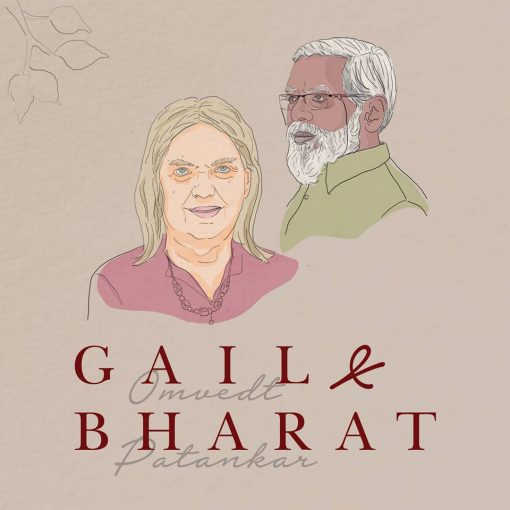

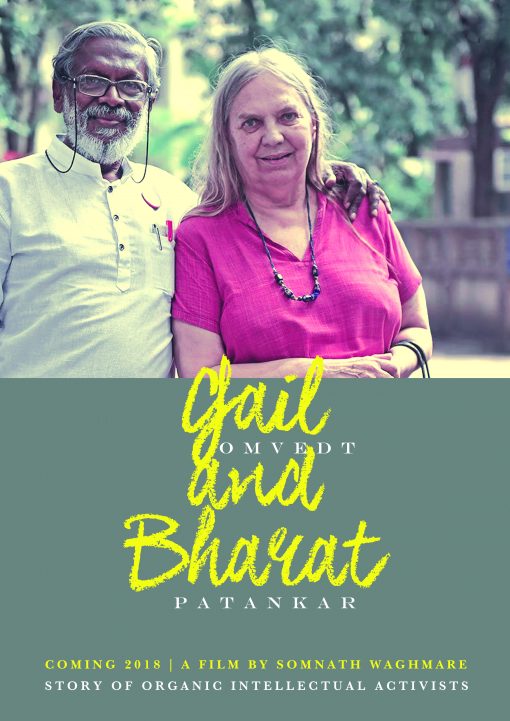

Lourdes M Supriya (LMS): Could you talk a little about Gail Omvedt and Bharat Patankar’s work?

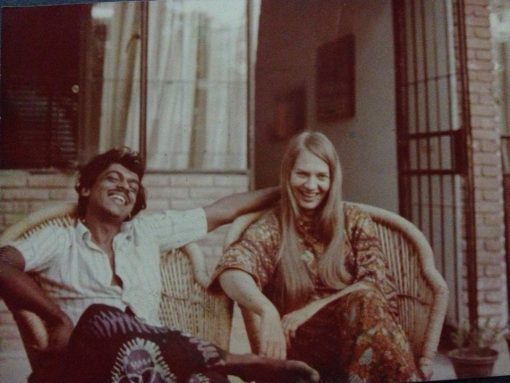

Somnath Waghmare (SW): Gail came to India to do her PhD research on the non-Brahmin movement of Maharashtra, primarily Phule’s movement. That was 40 years ago. She completed her PhD, went back to the USand taught there for some time, before coming back and settling down permanently in India. She got an Indian citizenship in 1983.

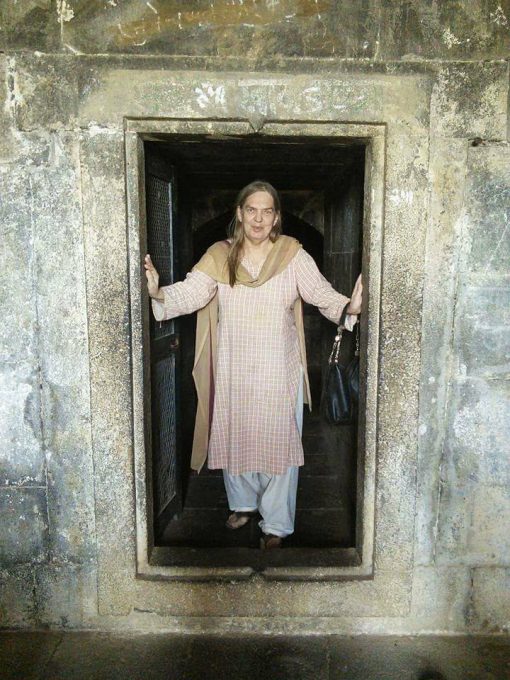

Her primary focus is on the anti-caste struggle. She’s written many academic articles on Phule and Ambedkar’s anti-caste struggles; they have been published in international publications. She’s also written about other social reform movements like the Varkari movement, the Satyashodhak movement. She’s also a grass-root level activist. She still works with the communities that are the focus of her academic studies.

In Maharashtra, some important Left leaders — and this is why Maharashtra’s Left movement is slightly different from North India’s —have led important anti-caste movements and have done a lot of work on caste violence and caste-related social ills. Patankar is also one such leader; his organisation, the Shramik Mukti Dal has been working in Maharashtra for decades now.They work with many communities; for instance, farmers displaced by dams. Patankar has worked quite a bit on accessibility of water.

He was one of the leaders of the farmer’s movement in Sangli, Maharashtra, which had precipitated in the farmers building the Bali Raja Dam. Till date, it remains the only dam that has been entirely built and managed by the people.

LMS: What were your reasons for making this documentary?

SW: Why I made this documentary—and this is also why I made my other documentary on Bhima Koregaon, which is now available to the public for free on YouTube — was to increase awareness about Gail Omvedt and Bharat Patankar’s work. Academicians, and other social activists and leaders, might be aware of their work. But outside of the communities they work with, not many people know them. Their work hasn’t been given the recognition it deserves by the government; none of the national dailies have interviewed them or written about their work. They don’t have the kind of exposure that they deserve. And this, almost inconspicuous, invisibilising of anyone who leads anti-caste movements needs to be challenged and questioned. And this can be done by documenting these stories, and bringing them to the people.

Although Gail Omvedt is known in the academic circles, her work extends much beyond academics. But she is hardly recognised outside these circles. This is why I’m doing the film.

Bharat Patankar — he’s actually a doctor, a gynaecologist, by profession — comes from a family that was actively involved in the freedom movement and has been a part of the anti-caste movement in Maharashtra. His mother, Indumati, worked among the people till her death last year. Gail Omvedt gave up all the privileges that come with being an American and an American citizen, came to India, took up Indian citizenship, and now lives in a village and works with the people at the grassroots.

These people choose to stay in a village and work among, and with, the people. But there are no movies being made on them; they haven’t got any major awards either. I want to make their work and their contributions a part of the public discourse. I want to show how their work is still as relevant as it was when they began. In fact, it is even more so, because caste atrocities have suddenly escalated; there’s an increase in violence against the scheduled castes.

Much of the documentary follows them in the present, the meetings they organise, the rallies they attend, how they go about their daily lives. But it’s not just about them. It also talks about the contemporary cultural and political situation in Maharashtra. That is also very much part of the documentary.

LMS: You mentioned that caste atrocities have escalated and that was one the reasons you’re making this movie at this point of time. But what prompted you to make a documentary on Omvedt and Patankar specifically, and not any other anti-caste activist?

SW: See, I’m not just a filmmaker. I’m also a student. Caste is not an “area of interest”, it is also an experienced reality. I have been studying caste academically for some time now. There are four important intellectuals whom I consider important when it comes to studying caste — Mahatma Phule, Baba sahib Ambedkar, Kancha Illaiah, and Gail Omvedt. They’ve made significant contributions to the academic study of caste. In fact, it is through my readings on caste that I first came across Omvedt’s work.

Omvedt and Patankar have led many popular campaigns in Maharashtra. One of them was a campaign demanding the abolition of the practice of appointing a temple pandit, a temple priest. They began this campaign from the Pandharpur temple, Solapur, Maharashtra. It’s a Varkari temple but they also had a temple priest. They had also written quite a lot during the entire campaign about it. Despite having led such popular campaigns and movements, not many people know of them.

Some time back, Scroll published a list of 5 important public intellectuals. That had sparked a debate: is Gail Omvedt not a public intellectual? I realised how little people knew of her outside of academic and activist circles; and that this had as much to do with her geographical location as with the nature of nature of her work. That was also one of the things that prompted me to make this documentary now, and on Omvedt and Patankar’swork.

LMS: Why do you think she hasn’t gotten the recognition she deserves?

SW: It’s because she works on anti-caste issues, something that is often brushed under the carpet. How often do you see grassroot level anti-caste activists getting attention from mainstream media? It has also, perhaps, got something to do with her involvement in Bahujan politics. She has had a hand in laying the intellection foundation of the Bahujan Samaj Party.

Kanshi Ram, who founded Bahujan Samaj Party, lived in Maharashtra for some 12 years; he was an officer in Pune. He narrated an incident from his time there in a small book that he wrote during BSP’s formative years. After deciding that he wanted to explore and understand the writings of Phule and Ambedkar, he travelled from Mumbai to Kasegaon to meet a woman who, he had been told, had worked extensively on Ambedkar and Phule. He credited her with being the one who helped him evolve his own politics; who explained to him what Ambedkar’s writings were, what his politics stood for; who told him about Phule. “She is Gail Omvedt”, he wrote.

The problem is, the film industry, even the documentary scene, is dominated by those who belong to the savarna castes. For them, such stories are not important. Films like Kaala are being made now, and more such films will be made now that the awareness among dalit and bahujan communities has also increased, with increase in access to education. Cinema is made based on our personal experiences. So, of course, dalits and bahujans in the industries are going to make such movies. Now that they have the means, of course they are going to tell their own stories.

LMS: What is your vision for this documentary?

SW: I don’t want it to be too academic. I think a documentary should be both informative and interesting, engaging. I want people who may not have a background in academics or an interest in social work to also watch and understand it; to be able to relate to it.

What often happens is that when forward cast documentary filmmakers make movies on dalit and bahujan communities, they do so from an outsider’s perspective. They tend to reduce dalits and bahujans to hapless victims. Their understanding of caste often gets coloured because of their own caste location. This makes the dalit and bahujan viewers uncomfortable.

I want to make sure I don’t do that. Since I am also from a scheduled caste community, I have made the documentary from an insider’s perspective.

LMS: Since both Gail and Bharat are important anti-caste movement leaders, would it be fair to say that your documentary is also about the anti-caste struggle?

SW: Yes, it is.

See, essentially, there are only two states in India that have seen significant anti-caste movements — Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. Call it anti-caste, anti-brahmanical, whatever. But these two states have seen massive movements against the caste system.

Now, Maharashtra has a popular Varkari religion movement; this movement traditionally prays to saints, not gods. We can also call this a “saint tradition”. Before Shivaji, there were a lot of saints that people prayed to. Such traditions were borne out of differences with the hierarchical caste system; they opposed it. There are examples of such movements in Tamil Nadu also. For instance, there was Periyar who led movements against the oppression by dominant castes.

A lot of people have written against the caste system; they have devoted their entire life towards its abolition. Mahatma Phule, who was a very important philosopher, also wrote about it. But because he wrote in Marathi, he was ignored by mainstream academicians for a long time; he was not recognised as an intellectual philosopher for a long time.

So, Maharashtra has had a long history of anti-caste struggle; from the saint tradition, to Shivaji and Sambhaji.

Now, education, literacy, knowledge, these are things that dalits and bahujans were not given access to. Plus, no women, from any caste whatsoever, had access to these. So who held the knowledge? It’s the men in the forward castes. Historically, it’s primarily men from these castes who get to study, who are literature. Consequently, they are the ones who write history, isn’t it? So it’s no wonder that people who’ve led anti-caste movements hardly get a mention or are misrepresented, ignored. Phule was never considered an intellectual; Varkari movement did not get the attention it does now.

In fact, Shivaji has been misrepresented and appropriated by most savarna historians. For instance, Balwant Purandare wrote a play on Shivaji that showed him as anti-dalit, anti-Muslim. This is not true and there were people who spoke up against it. He was, in fact, a secular and progressive king. This has been written about by other historians and activists like Comrade Pansare. There was another book on Shivaji, by James Laine, that led to a lot of controversy.

What all these things only prove that cinema, drama, plays, all these things are also political in nature. My film is no different.

LMS: I understand that it is not possible to include absolutely everything about a subject in a single documentary. So what can we expect to see in your documentary?

SW: The film, as it stands now, is about their contribution to social movements, Omvedt’s academic work — she had written quite a bit as an academic — and about Bharat’s work with the community. It also includes stories from their life and experiences.

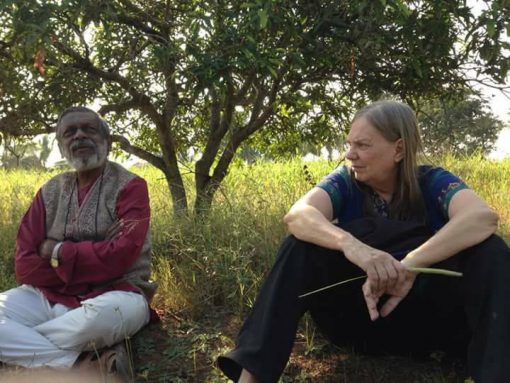

It essentially traces their stories, the work done by them in the past — their cultural and political contributions; their work with the community (like Bharat’s work on water), among other things. I’ve been travelling with them for the past six months and shooting.

The film will focus on a few of the campaigns and struggles that Gail and Bharat have led, and talk about the larger contributions that they’ve made through these things.

There are many stories about them and the kind of impact that their work has had. I want to bring these out through my documentary. For instance, one of the stories about Gail is from her first visit to India. She came when she was 27 years old. At the time, most dominant castes in villages did not allow Ambedkar Jayanti to be celebrated. On this trip, Omvedt and Indutai (as Bharat’s mother is fondly called) went from village to village, to the dalit bastis there, and told them about Ambedkar, his work on caste, and encouraged them to celebrate Ambedkar Jayanti to instil a sense of caste pride I them. They organised many such Ambedkar Jayanti celebrations.

These are the kind of stories I want to bring out through my documentary.

LMS: You mentioned that you travelled with Omvedt and Patankar, that you went to Kasegaon and spent time there. Considering that you’re a full time student at Tata Institute of Social Sciences these days, how did you find the time and the resources to make the film?

SW: Yes, it is hard but that is the only way I could make this documentary. I spent all the breaks and holidays that I got from TISS with them. In fact, I just spent my last vacation with them. I accompany them to their meetings, to rallies, to functions.

This film is entirely crowd funded. It is not being funded by any corporate producer. It is mostly the people I’ve met in progressive circles, like people from the Ambedkarite movement, who have given some amount. Everyone has donated according to their means; people who understand and value the importance of Gail and Bharat’s work.

If you want to help Somnath Waghmare raise funds for the documentary, click here.