The fact that William Shakespeare has suddenly become a point of attraction to Indians is not factually true. Shakespeare has remained omnipresent in literary critique by scholars for a very long time. Perhaps we are noticing the appeal now because of a flood of varied celluloid representations of Shakespeare’s works, Indian filmmakers across the map are showing interest in.

The earliest documented reference one could discover is Shakespeare Through Eastern Eyes by Ranjee Shahani, published in 1932 during the heights of Indian nationalism and the Round Table Conference. Shahani aspired to bring out an Indian response to the plays by taking into account differences between race, culture and ethnicity. Smarajit Dutt’s critical texts on Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth all carry the subtitle ‘An Oriental Study’ are emphatic about describing their critical objectives. Other scholars have tried to bring out comparisons between Kalidasa and Shakespeare’s works which have prioritised Kalidasa over Shakespeare, concluding that while Kalidasa inscribed a national identity, Shakespeare could be termed “provincial.[1]

In the over 450 years of his demise, Shakespeare has passed on more than just his works. He has inspired several generations of filmmakers across the world with ideas through his plays which offer some of the best ingredients for a mainstream film in any language and that could belong to any culture, ethnic backdrop, time-space paradigms, relationships, and so on. His works have the universality to transcend the confines of the written word, albeit in an English that is no longer in vogue, with characters that belong to a different era and a different culture and backdrop altogether.

The question that arises in this context is – Can a celluloid transposition of a Shakespeare play be termed an “adaptation,” a “transcreation,” a “translation”, an “interpretation”, a “contemporisation” or even “appropriation” or a “re-localisation in terms of language, culture, geography” and so on? The plethora of Indian films, be it in Hindi, Bengali, or any other regional languages prove that they are all of these and some more because they add to the Bard’s creations in their own way. One reason for the large number of celluloid versions of Shakespeare may have sprung from the fact that Indian cinema, in spite of being the largest producer of films across the world, is considered to be “lowbrow and unworthy of attention.” The filmmakers, perhaps subconsciously aspired to break through this low perception by the world outside, and ventured to correct this wrong notion about Indian cinema in general and Bollywood in particular.[2]

Khoon Ka Khoon (1935), an Indian adaptation of Hamlet, written by Mehdi Ahsan has Sohrab Modi enacting Hamlet, Naseem Bano as Ophelia, and Shamshad Bai as Gertrude. Following Sohrab Modi, in 1941, J. J. Madan adapted The Merchant of Venice for his Hindi film titled, Zalim. Romeo and Juliet was adapted of late by Sanjay Leela Bhansali as Goliyon Ki Rasleela Ramleela (2013) in a Gujarati milieu. The Montague-Capulet family rivalry was reflected in the Rajadi-Sanera family conflict. Death of Ram (Romeo) and his beloved Leela (Juliet) finally ended the bloodshed between their families.[3]It was a highly glamorised, lavishly mounted, star-studded, exaggerated melodrama that played more around the erotic nuances between the lovers than on the familial conflict, though the matriarch did her bit of loud acting and designed posturing.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, this trend of adaptation flourished with the release of Angoor (1982) directed by Sampooran Singh Kalra (Gulzar). Angoor was a remake of Bhrantibilas (1963), a Bengali comedy film based on a Bengali play of the same name, written by Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar. Vidyasagar’s play was an adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors. A recent remake of Angoor directed by Sajid Khan titled, Hamshakals was a distortion that turned out to be a horror and thankfully, flopped in its theatrical release. The Bengali celluloid version of Bhrantibilas, however, was a major commercial hit and is a favourite among television couch potatoes even today.

Vishal Bhardwaj’s adaptation of Macbeth into Maqbool (2004) and Othello into Omkara (2006) followed by Hamlet as Haider (2014), are sincere attempts to investigate and understand how Shakespeare can be and has been appropriated into the national ethos and also fitted neatly into a very typically Indian socio-political setting of Northern India with all its class distinctions and existing social stratums, and furthermore, how they can still function as independent works of art. While Maqbool is set against the backdrop of the Mumbai underworld, Omkara is relocated in the feudal heartlands of northern India.

Maqbool interprets Macbeth in the most unlikely of settings. An attempt as ambitious as this is a challenge even for the most accomplished of craftsmen. Maqbool effectively abstracts the essential Macbeth out of its original theatrical structure and renders it in a form that is very much contemporary cinema. Macbeth, the character, happens to be one of Shakespeare’s most profound visions of evil concretised as a character. In Maqbool, Macbeth is relocated within an entirely human paradigm. Maqbool narrates the tale of a particular human situation in which a complex interplay of human emotions results in a grave crisis. The script of the film closely follows the architecture of the original play and remains true to its theme.

Haider, however, is an altogether different story. Set in the time frame of the turbulence of the 1990s, with Kashmir as its backdrop, Bharadwaj’s Haider became the “most acclaimed and contentious Bollywood movie of the year,” according to Vaibhav Vats in The New York Times (October 27 2014.) At the 62nd National Film Awards, Haider won five awards, leaving behind all other films. While Shahid Kapoor won the Best Actor Award, Bharadwaj bagged awards for Best Music Direction, Best Direction and Best Screenplay.

Margaret Jane Kidnie in her seminal work, Shakespeare and the Problem of Adaptation (2009), contends that, “Cultural, geographical or ideological differences between work and adaptation are rooted in a perceived temporal gap between work and adaptation enabled by an idea of the work not as process, but as something readily identifiable instead as an object” (68-69). This makes it clear that certain differences are unavoidable and that adaptations do lead to certain problems.

When a text is adapted for a film, it is trimmed to counter the issue of time and space. This shortening may lead to a quality compromise. The author’s genuine intention is overlooked in such a collaborative venture of moviemaking, and often the participation of the viewer is strictly limited, contrary to the process of reading where a reader has the liberty to participate in shaping the meaning of the text.[4]

In Shakespeare and the Ethics of Appropriation, (Palgrave MacMillan 2014) Alexa Huang and Elizabeth Rivlin write, “Reproducing Shakespeare marks the turn in adaptation studies toward recontextualisation, reformatting, and media convergence. It builds on two decades of growing interest in the “afterlife” of Shakespeare, showcasing some of the best new work of this kind currently being produced.” However, there is very little reference to cinema and absolutely no reference to Indian film adaptations of Shakespeare’s works since this book deals mostly with replications in literature, theatrical performances and so on.

Parthajit Baruah, a noted film critic who has done considerable research on cinematic interpretations and transpositions of Shakespeare’s works in Assam, says, “The critical acclaim that Shakespeare has attained in this country is not new and ‘sudden’. The Shakespearean motifs have long been inspiring the Indian film-makers, although it is Vishal Bhardwaj who explicitly engaged with the themes of some of the Bard’s great tragedies. The reason is the universality of Shakespearean characters and human conditions represented by them. Another reason may be an Oriental fascination for Western masters, where Shakespeare is just an image of the West and its literary products.”

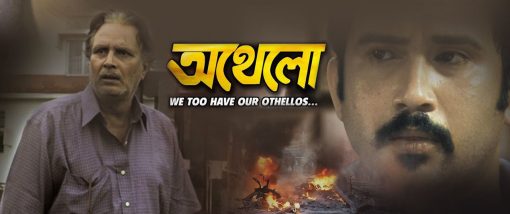

“This however, cannot simply be defined in terms of the outcome of an imperialist project where Shakespeare is orientalised because Shakespeare has been carried across languages and cultures in a such way that his motifs have become universal — they no longer belong to the West in the present context. Shakespeare’s plays and Assamese cinema, in spite of the vast differences in time of creation and background, bear parallel sensibilities in the way they express the socio-political impression of their times. One such instance is Hemanta Kr Das’s Assamese film Othello (We too have our Othellos) where some Assamese characters have represented the ‘Otherness’ of Shakespeare’s Othello. The racial otherness of Shakespeare’s Othello is transformed to an experience of otherness conditioned by social hierarchy and taboo. In the Assamese adaptation of Othello, thus, the Shakespearean treatment of otherness has been localised and culturally contextualised,” Baruah sums up.

All this finally boils down to that one million-dollar question – Why is Shakespeare so popular among Indian filmmakers and, the Indian audience since the box office returns of most of these celluloid versions are unexpectedly good? Jonathan Gil Harris in his article The Bard in Bollywood (The Hindu, April 23, 2016), writes: “It is easy to see Shakespeare as simply one of the legacies of British colonialism in India. But his popularity in Hindi cinema is not just the culmination of Thomas Macaulay’s Minutes on Indian Education (1835), in which the colonial official infamously declared that “a single shelf of a good European library [is] worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia”. It also has a lot to do with profound resonances between Shakespeare’s craft and Indian cultural forms that converge on one concept: masala.”

Taking off from this concept of masala, which popularly stands as both a synonym and a metaphor for the spicy features of any mainstream Indian film, is structurally and organically already present in almost every Shakespeare play that becomes the very basis for pulling both filmmakers and the audience towards his stories and their varied manifestations in a dozen different ways.

Every Shakespearian play, keeping its philosophical and ideological underpinnings aside for the sake of argument, is filled with every ingredient needed to make the final dish palatable, tasty, and delicious in that order. Shakespeare’s plays are filled with intrigue, melodrama, and colourful characters that cover a wide range between the extreme polarities of black and white, magic, jokers, and clowns used both as dramatic strategies and agencies as well as to bring relief in serious moments, romance, adultery, suspicion, betrayal in love, friendship and filial loyalty, objects that are construed differently and used dramatically (For instance, the handkerchief in Othello), and if all this is not enough, very strong and beautiful women characters.

What however, can easily place Shakespeare in their Indian celluloid versions is the unique “Indianness” they are vested with by the makers, the script and the relocation of the characters, their relationships and events create a distinct pattern of a definite genre in cinema distanced from other genres.

In his insightful paper, Shakespeare-wallah : Cultural Negotiation of Adaptation and Appropriation,[5] Souraj Dutta writes, “Maqbool draws upon the mainstream popularity of movies based on the Mumbai underworld, a genre established firmly in the 90s by films like Mahesh Bhatt’s Sadak (1991), Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya (1998) and Company (2002), Mahesh Manjrekar’s Vaastav (1999), etc. However, the film steps aside from the exaggerated and high-crying drama, dialogue, and action that would be expected from such a film and reaches for a more muted and resultantly poignant mood. It is also highly successful in fusing together the key elements of the Shakespeare play with the theme setting of the underworld, a genre marked by its boundaries with urbanity.” With subsequent works however, Bharadwaj slowly emerged out of his subtle and low-key treatment to progressively turn louder, more glamorous and overstated drama. Was it for commercial compromise? One is not cannot be quite sure, but the film was a big hit both in India and overseas.

In April 2016, a conference on Indian Shakespeares on Screen was jointly organized by the British Film Institute and the University of London to celebrate 400 years of the Bard’s death. The organisers felt that Hrid Majharey, a Bengali film directed by Ranjan Ghosh, incorporates “stylistic elements, themes and narrative devices that make it both self-reflexive and in keeping with Shakespearean traditions. Ghosh’s cinematic treatment of Hrid Majharey through intertextual references and mise-en-scene are refreshing and effective precisely because it is able to circumvent the colonial implications and gravitas of Bengal’s literary/cultural heritage – frameworks that are usually employed in a discussion of Shakespeare in Bengal – modifying and playing with Shakespeare’s characters/styles in order to make his own statement about what Shakespeare means to a contemporary audience.”

“Drawing on Othello, Hamlet, Julius Caesar and Macbeth, Ghosh’s Hrid Majharey (Live in my Heart, 2014) throbs with intertextual references and mise-en-scene that bears the imprints of a classic Shakespearean tragedy,” wrote Priyanjali Sen in her paper called, Shakespeare and Contemporary Bengali Cinema: Form, Intertextuality and Mise-en-scene in Hrid Majharey (2014) and Arshinagar (2015). Arshinagar can be seen as a contemporary, urban and stylised take on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet directed by Aparna Sen.

In 2015, Hrid Majharey was included in a Ph.D. thesis entitled ‘Shakespeare and Indian Cinema’ at the Tisch School of Arts at New York University. The Film Faculty at the Tisch School of Arts felt that Hrid Majharey was refreshing in that it successfully managed to break away from any colonial implications linked to Bengal’s British part by giving it an entirely independent and topical feel. In the same year, Oxford, Cambridge and Royal Society of Arts (OCR) Examination Board (similar to the CBSE Board in India) enlisted Hrid Majharey as a reference film grouped within “World Adaptations of Othello” in the syllabus for its A-Level Drama and Theatre course under the title Heroes and Villains – Othello. Among the nine films included in the course are films such as A Double Life (USA, 1947), All Night Long (UK, 1962), Catch My Soul (USA, 1974) and Omkara (India, 2006.)

Franco Zeffirelli who made three Shakespeare adaptations on film namely The Taming of the Shrew (1966), Romeo and Juliet (1968) and Hamlet (1990) presents the ideal recreation of Shakespeare on film when he says:, “I have always felt sure I could break the myth that Shakespeare on stage and screen is only an exercise for the intellectual. I want his plays to be enjoyed by ordinary people.” Some of the Indian adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays prove the same and therefore, in this sense, Vishal Bharadwaj’s trilogy of Shakespeare and Ghosh’s Hrid Majharey will stand the test of time, space, culture, and language now and forever.

[1] Kapadia, Parmita: Bastardizing the Bard: Appropriating Shakespeare’s Plays in Post-Colonial India, Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachussetts, Amherst, May, 1997.

[2] Craig Dionne and Parmita Kapadia (eds), Bollywood Shakespeares (New York, Palgrave Macmilla2014),