On 19 May Girish Karnad, the Kannada playwright, actor, and director turned 80. Karnad has been of the most influential playwrights in post-independent India. He is known to use mythology to depict a contemporary crisis. Besides serving in several public institutions like the Sangeet Natak Akademi, he is also one of the most important public intellectuals of his time. Inspite of his ailing health, he came out to participate in the #NotinMyName protests that broke out across the country after several incidents of mob lynchings.

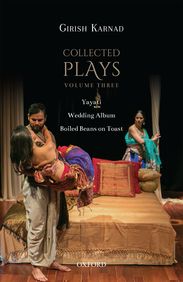

In this introduction from the third volume of Collected Plays by Girish Karnad, the critic and academic Aparna Bhargava Dharwadkar mentions a lively theatre culture in post-independent India that sprung up in the 60s. Karnad began his career in the theatre in this milieu. She traces some of the common elements in Karnad’s playwrighting practice that spans several decades through her discussion of three plays: his first, Yayati; Wedding Album; and his latest play, Boiled Beans on Toast.

Introduction

Aparna Bhargava Dharwadkar

In an interview with me recorded in 1993 and published in 1995, Girish Karnad made the following observation in response to a question about how the lack of serious criticism affects the arts in India.

I must emphasize here that the sudden spurt in serious playwriting in the 1960s was strengthened by the number of committed, intelligent, and active people who came into the amateur or semi-professional theatre scene at that time. Alkazi, Sombhu Mitra, Utpal Dutt, and Habib Tanvir were already there. And suddenly there were Satyadev Dubey, Shyamanand Jalan, Arvind and Sulabha Deshpande, Rajinder Nath, Kavalam Panikkar, G. Sankara Pillai, B.V. Karanth, Om Shivpuri… We all reacted to each other’s work. There was endless discussion… We playwrights translated each other’s work. I miss all that dearly.

What Karnad was evoking implicitly in these comments were the mechanisms and processes by which mainstream urban Indian theatre was formed as a post-Independence field of practice, without the systemic stimulus of a functioning theatrical marketplace. In artistic terms, there were four critical factors that made this unusual performance economy possible — playwrights around the country kept up a steady stream of plays that were notable successes both in print and performance; gifted directors (who also often doubled as playwrights) brought new work quickly onto the stage, in collaboration with their groups of actors, designers, and technicians; a cadre of competent and active translators made new plays, as well as Indian, Western, and world theatre from various other periods, available in multiple languages so that the works could circulate nationally; and a relatively small but loyal body of viewers extended enough support to the entire enterprise to make it viable. In material terms, there was strategic support from national and state-level public and private institutions, such as the central and regional Sangeet Natak Akademis, the National School of Drama (NSD), the Shri Ram Centre for Art and Culture, and Bharat Bhavan. Through programmes of training, development of repertory companies, grants, fellowships, subsidies, and sponsored events, these organizations offered a range of opportunities that were more or less accessible to individuals and groups, and sustained their work in varying degrees.

Twenty-four years after Karnad’s comments during the interview, the period of creative ferment he recalled with such nostalgia has receded even more irrevocably into the past. There is a widespread sense among all those involved with urban theatre in India that circumstances today are qualitatively different from the formative conditions that had emerged during the 1960s, and were in evidence even until the late 1980s. One explanation for this change is the inevitable generational shift — with the exception of Ebrahim Alkazi and Rajinder Nath (neither of whom has been an active director for some time), the practitioners Karnad mentioned in 1993 are no longer living, and many other iconic careers, including those of Vijay Tendulkar, Badal Sircar, G.P. Deshpande, and K.V. Subbanna, have also come to an end. But there have been substantial artistic, material, sociological, cultural, and political shifts as well to account for the current sense of difference and distance. The majority of new plays now seem to lack the qualities that had transformed a large number of earlier works into ‘instant classics’, from Sircar’s Ebong Indrajit (And Indrajit, 1962) and Karnad’s Tughlaq (1964) to Satish Alekar’s Begum Barve (1979) and Vijay Tendulkar’s Kanyadaan (1983). The pressures of a neo-liberal economy and the continuing problem of resources have pushed theatre workers into increased dependence on corporate sponsorship, philanthropy, and institutional patronage.

Hence, annual events such as the NSD’s Bharat Rang Mahotsav (India Theatre Festival), the Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards endowed by the Mahindra Company, and the calendar of the National Centre for Performing Arts carry disproportionate weight in the process by which good theatre is made available to audiences for a reasonable cost. Other active institutions, such as Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai, the Shri Ram Centre for Art and Culture in Delhi, and Ranga Shankara in Bengaluru have to take on some purely revenue-generating activities so that they can support their own artistic initiatives. The arrival of colour television in India in 1982 dealt theatre a blow from which it has not managed to recover fully, and in many Indian cities, the problems of negotiating traffic keep that television-watching audience at home in the evenings, leading to a significant decline in the audience for theatre. Counterpointing these struggles for survival is the perception that the real momentum in theatre now belongs not to the predominantly male, middle-class, somewhat complacent urban mainstream but to the forms of subversion, resistance, and protest represented by women’s theatre, street theatre, Dalit theatre, gay and lesbian theatre, experimental political theatre, and applied theatre of various kinds. With the further weakening of live theatre by the exponential increase in new digital media, and the daily pressures of a polity in crisis, creative energy is said to be seeping out from the metropolitan centre, into oppositional forms at the periphery.

In 2017, the seventieth anniversary of Indian independence, Girish Karnad is a singularly intriguing figure to place against this narrative of centralization and dispersal because his nearly sixty-year career in the theatre encompasses the post-Independence arc fully, and indeed brings it full circle. There could not be a more remarkable confirmation of this cyclicity than the present volume, which opens with Karnad’s very first play, Yayati (published in Kannada in 1961), and then moves on to his two most recent works, Wedding Album (written originally in Kannada as Maduveya Album, 2009), and Boiled Beans on Toast (written originally in Kannada as Benda Kaalu on Toast, 2014). This unusual conjuncture requires some explanation so that the post-2005 phase of the playwright’s career can come more clearly into view. As Karnad has noted frequently in print, Yayati was written during the period of psychological turmoil in 1960 when his impending departure for Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar created anxiety in his family about his return. At that time, every major feature of the work had taken the twenty-two-year-old author by surprise — that is was a play and not a cluster of angst-ridden poems, that it was written in Kannada instead of English, and that it used an episode from the Mahabharata as its narrative basis instead of creating an Oedipal psychodrama set in the present. ‘The myth,’ Karnad acknowledges, ‘nailed me to my past’, and it also initiated a preference for narratives from the past which dominated his playwriting for the next four decades. In my Introduction to Volume 1 of his Collected Plays (2005), I mapped this preference as a cycle of myth-history-folklore, which, in different permutations, informed all but one of Karnad’s published plays from 1961 to 2005: myth in Yayati, Agni Mattu Malé (The Fire and the Rain, 1994), and Bali: The Sacrifice (2002); history in Tughlaq (1964), Talé-Dan ̣d ̣a (Death by Decapitation, 1990), and The Dreams of Tipu Sultan (1997); folklore in Hayavadana (Horse-Head, 1971), Nāga-Mandala (Play with a Cobra, 1988), and Flowers: A Monologue (2004).

The exception was Broken Images (2004), the first of Karnad’s plays to be set in the urban present, and one that was written and performed almost simultaneously in English and Kannada, but dealt with the specific politics and economics of English as a creative medium in relation to a strong ‘regional’ language such as Kannada. Manjula Nayak, a self-possessed thirty-something who has been a well-known short-story writer in Kannada suddenly publishes a bestselling novel in English, and becomes a national and international celebrity — ‘The Literary Phenomenon of the Decade’. Following a live televised address to viewers, a surreal dialogue with her own image on the TV screen in the studio gradually reveals that Manjula has plagiarized the novel from her younger sister, Malini, a lifelong invalid and brilliantly gifted writer in English who had died a few months before the novel appeared. Manjula discovered the novel, signed ‘M. Nayak’, in her husband Pramod’s desk drawer immediately after Malini’s death, sent it to a literary agent in England, and decided to seize the opportunity when the agent and the publisher assumed she was the author.

The decision has brought her wealth and fame, but ended her marriage to Pramod, who was in love with Malini and knew the truth about the novel. At the end of the short play, Manjula declares that she has morphed into Malini, the dead sister who now clearly controls her body, her mind, and her duplicitous future life. Placed against this forty-year trajectory, the three plays included in this volume present suggestive patterns of similarity and difference. In one perspective, Yayati is a play from 1961, representing myth as primary subject matter, Kannada as the language of original composition, and Karnad’s disconnection from the theatre world as the determining condition of its dramaturgical structure. In another perspective, it is a play from 2008 (the year of its publication as an individual work), rewritten in both English and Kannada in light of the insights, suggestions, and critical comments offered by ‘professionals who have actually staged it’, not to mention the authorial experience Karnad could bring to bear on it after more than four decades of playwriting. The play’s exclusion from Volume 1 of the Collected Plays in 2005 also reflects Karnad’s fastidiousness as an author and translator, which led to his decision not to authorize, especially in the potentially global medium of English, a work with which he ‘continued to feel dissatisfied’, but which he was eventually persuaded to publish in his own English translation. The unusual textual history of Yayati both in Kannada and English, and its anomalously long trek towards publication in English, are reminders of the circuitousness that sometimes interrupts the linear progression of literary and theatrical careers. In contrast, the two other plays, Wedding Album and Boiled Beans on Toast, are in part continuations of the change in direction signalled by Broken Images — although both were written originally in Kannada and then translated by Karnad into English, they are concerned with urban life in the present, and use two Karnataka cities as their setting: Dharwad and Bengaluru in the former, Bengaluru in the latter. In other important respects, however, all three plays are comparable — each deals in its own particular way with familial conflicts, and each foregrounds the lives of women. These patterns can be outlined in general terms here, and elaborated in the individual discussions that follow. The title character in Yayati is a mythic king whose egotism and coarse sensuality would qualify him as an ‘anti-hero’ in the modernist tradition of Jean Anouilh, and the play follows the counter-Oedipal logic of the traditional Indian family structure, which leads a self-doubting son to surrender to the will of a self-centred father, even though his decision destroys many lives. Much more prominent than the drama of male generational conflict in the play, however, are the volatile relationships between four self-possessed, articulate women—the queen, the mistress, the loyal servant, and the young bride—all of whom, as I noted, ‘are subject in varying degrees to the whims of men, but succeed in subverting the male world through an assertion of their own rights and privileges’. In Wedding Album, the tensions in the middle-class nuclear family of five run beneath the surface, and the moments of emotional trauma happen mostly off stage. But the patriarch has now shrunk into an inarticulate old man prone to occasional outbursts, and the son has become a facilitator who does not hesitate to use his family members as material for television melodrama, and gives in to a marriage of convenience. Once again, four women claim most of our attention—a somewhat guilt-ridden mother who has done her duty by her husband, but not all her children; a discontented older daughter who is married and lives abroad; a younger daughter who makes a questionable choice of husband in the course of the play; and an old servant whose abandonment of her own daughter forms the under-stated climax of the action. In Boiled Beans on Toast, the ‘man of the house’ within the main family is a nameless provider who does not appear on stage at all, the teenage son is in the process of finding himself, the life of an ambitious young professional is wrecked with brutal casualness, a vindictive brother forces his sister to break off family ties, and a few other men have walk-on parts (as policemen, autorickshaw drivers, and so on). Much of the focus is on the unusual friendship between two ethically dissimilar women of privilege (a hospice volunteer and an amoral fantasist), and the rivalry between two ethically dissimilar female servants jockeying for position in upper-class homes as they try to survive in the ‘monster city’ of Bengaluru.

In fact, when the twelve works gathered in all three volumes of Karnad’s Collected Plays (covering the period 1961–2014) are considered together from the viewpoint of gender, other interesting patterns emerge. The history plays are constrained to a large extent by their historiographic sources, and their focus on a premodern political world that does not allow women much agency. Hence, the Stepmother is the only significant female character in Tughlaq, and Karnad’s inventive energy goes into creating a range of historical and fictional male alter egos for the title character, especially the master-manipulator Aziz.

The same is true of The Dreams of Tipu Sultan, in which the queen, Ruqayya Banu, appears with her young sons in only one scene, and dies soon afterwards, unaware that her children are being bartered for the sake of the kingdom. In the crowded historical canvas of Talé-Dan ̣d ̣a, there are principal male as well as female characters, but the affective emphasis is on the communities of men, women, and children who are destroyed by caste violence when a reformist socio-religious movement becomes a deadly political tool. The plays based on myth and folklore, however, place women at the centre as desirable and desiring subjects, whether we consider the triad of Devayani–Sharmishtha–Chitralekha in Yayati, Padmini in Hayavadana, Rani in Nāga-Mandala, Vishakha and Nittilai in Agni Mattu Malé, or the Queen in Bali. In a third variation, women in the three ‘plays of the present’, beginning with Manjula in Broken Images, are mundane and in many cases ethically compromised figures, caught up in an urban domestic and social world that lacks charm and charisma. The following discussions reinforce that the value Karnad places on female subjectivity in his fictions of the past (for example, Yayati) undergoes an ironic decline in his fictions of the present (Wedding Album and Boiled Beans on Toast), pointing to a central difference in his imagining of the premodern and modern worlds.

Here is a documentary on Karnad Nadedu Banda Daari made by the director K M Chaitanya.

In the next excerpt, we publish the beginning of the Prologue in Karnad’s first play Yayati.

Yayati

Girish Karnad

Prologue

The Sutradhara enters and addresses the audience.

Sutradhara: Good evening. I am the Sutradhara, which literally means ‘the holder of strings’. It has been argued by some scholars that this title establishes my lineage back to the puppeteer, the manipulator of marionettes. But others, equally eminent, have said the string, being an instrument of measurement, actually points to my descent from the carpenter, the prop-maker or the architect. In effect, I am the person who has conceived the structures here, whether of brick and mortar or of words. I have designed and consecrated the stage. I am responsible for the choice of the text. And here I am now, to introduce the performance and to ensure that it takes place without any hindrance.

Our play this evening deals with an ancient myth. But, let me rush to explain, it is not a ‘mythological’. Heaven forbid! A mythological aims to plunge us into the sentiment of devotion. It sets out to prove that the sole reason for our suffering in this world is that we have forsaken our gods. The mythological is fiercely convinced that all suffering is merely a calculated test, devised by the gods, to check out our willingness to submit to their will. If we crush our egos and give ourselves up in surrender, divine grace will descend upon us and redeem us. There are no deaths in mythologicals, for no matter how hard you try, death cannot give meaning to anything that has gone before. It merely empties life of meaning.

Our play has no gods. And it deals with death. A key element in its plot is the ‘Sanjeevani’ vidya — the art of reviving the dead, which promises release from the limitations of the fleeting life this self is trapped in. The gods and the rakshasas have been killing each other from the beginning of time for the possession of this art. Humans have been struggling to master it. Sadly, we aspire to become immortal but cannot achieve the lucidity necessary to understand eternity. Death eludes definition. Time coils into a loop, reversing the order of youth and old age. Our certainties crumble in front of the stark demands of the heart.

We turn to ancient lore not because it offers any blinding revelation or hope of consolation, but because it provides fleeting glimpses of the fears and desires sleepless within us. It is a good way to get introduced to ourselves.

Enough however of circumlocution! Let us get on with the play. What is represented here on stage is an inner chamber on the firstfloor of King Yayati’s palace. The King’s son, Prince Pooru, is returning home today after many years of absence. He has successfully completed his education in the hermitage under renowned gurus, and is bringing home with him his bride, Chitralekha, the Princess of Anga.

Crowds have started collecting in the grounds around the palace, eager to see the royal couple. The two must enter this space and on this bed they must create for themselves the magic kingdom of love, ambition, and power. He must sow his seed here and then launch forth on a campaign of victory and death. She must proudly bear on her breasts the toothmarks incised by their offspring. Must. Nothing, however, ever happens as it must. What we have in front of us is not a well-charted map but a network of paths, many of which plunge into the shrubbery and disappear before we have even registered them.

But we must trust the narrative we have chosen for ourselves. Invent bits if necessary, but go on. We must relive, not a saga embedded in books, but a tale orally handed down by our grandmothers in lamplit corners.