I am very skeptical about literature festivals. I had only attended a few literature festivals — or ‘lit fests’, as they’re popularly known — in the past. I found it odd that a poet or a public intellectual would be flown to the city, be put up in reasonably luxurious hotels, and then flown back. All this expense for what? For just one session of poetry reading or one panel discussion. Organising a lit fest looked like an expensive enterprise. Recently, the government of Kerala not only granted government funds to private organisations, they also organised a lit fest. It was not very different from other corporate sponsored lit fests in terms of the speakers that they had and the themes of discussion.

This kind of commodification of literature can be detrimental to the higher ideals of art, if such a thing exists.

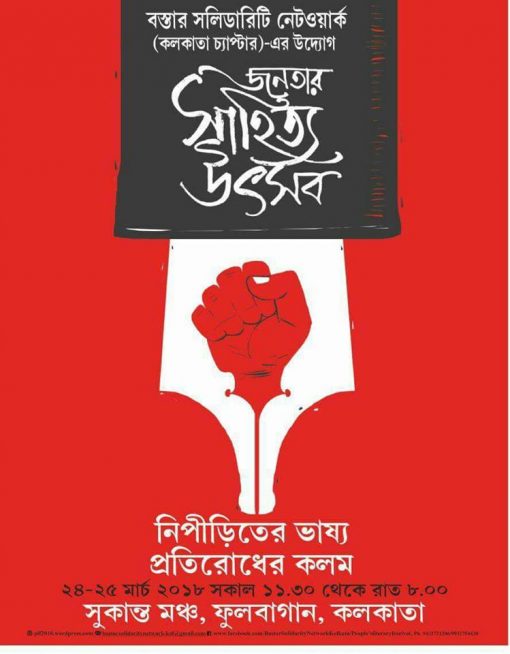

So a platform for literary discussions shorn of corporate sponsorship is like a whiff of fresh air and an audacious proposition indeed. I first heard about the People’s Lit Fest a while back. At the time, I had little idea of who was organising it, or where it was to going to happen.

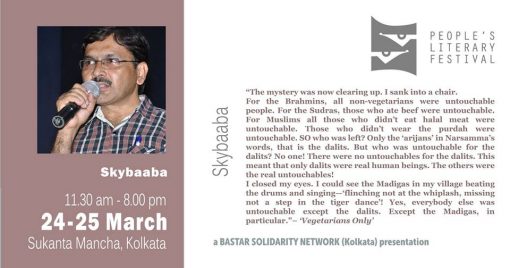

When I received the invitation, the first thing I noticed was that the organisers had made a clear and explicit policy statement on the plight of Muslims and the growing Islamophobia in the country. Their stand was well represented in a session with Skybaba, a Telugu Muslim writer, and Varavara Rao, a revolutionary poet.

Skybaba’s eloquent portrayal of the ordeal of a Muslim family while looking for an apartment to rent in the urban, middle-class, casteist Hyderabad. The icing on the cake was that his book, published by Oxford University Press, was available for purchase at the books counter of the lit fest. I am still reading the stories.They arevisceral. They describe situations which show how caste and other identities plague our lives even in the most cosmopolitan of spaces imaginable in contemporary India.

I used to be appalled at the intensity of Islamophobia in many of my Ambedkarite friends. A highly “literate” and “progressive” state like Kerala doesn’t have a writer of Skybaba’s calibre. We live in a world of paradoxes.

I found at least two speakers who were “regulars” in at other lit fest, veterans of the lit fest circuits. Perhaps their participation was necessitated due to the pressing need for a panoptic examination of “Talking Dirty” — the session the two said speakers were participating in. It was interesting how the moderator defined this term “talking dirty”. She described the range of “talking dirty” from caste-slurs to assertion of non-conformist sexual identities.

Although I was delighted with the felicitations extended to me, I think the audiences were more interested in sessions that were in Bangla or Hindi rather than in English.

However, the lion’s share of the discussions happened in English which may have been a major let down for the audience. Perhaps we need to look into the sociolinguists of languages — its accessibility, and privileges are inextricably intertwined with the languages we speak.

I also noticed that the kind of poetics and articulation that can be absorbed immediately, which does not require much work in the nuances of the “art form”, found wider resonance in the audience. At least, much more than those discussions which were more nuanced, and even, multilayered. Does this have to do with a larger debate between content and form? Or why activists tend to value “content’ or “subversive element” more than linguistic artistry?

My panel had poems by the tribal poet Jacintha Kerkatta — short, succinct, but also dynamites that the State would want to confiscate and quarantine. Here is a poem from her collection in English translation:

My pet dog was murdered

For the sole reason

That it had barked sensing danger.

Before being killed

It was declared rabid,

And I a “Naxal”

In public interest.

Another pleasant surprise speaker at the lit fest was a Palestinian activist. He began his session by first having one of the volunteers to read a Mahmoud Darwish poem in English translation. He followed this up by reading out the same poem in the original Arabic— a subtle act of asserting one’s own identity.

He then went on to talk about the current Modi regime’s complicity in the Palestinian genocide, pointing out how the Indian government uses taxpayers money to buy weapons worth billions of dollars from Israel, money which helps Israel continue their oppression of Palestinians.

Another session, which proved quite feisty, had two group taking turns singing songs in Hindi and Bengali. Their body language, their attire, and their ability to connect with the people immediately reminded me of the Kabir Kala Manch.

My engagement with this “people’s lit fest” left a deep impression on me. I made me consider the possibility of organising something similar in my small town by pooling in the resources of my Ambedkarite cohorts. To be radical is a privilege in itself.

In neoliberal times, when all marginalised sections are forced to fend for themselves, it is commendable if such collectives get together and organise a literary meet of writers who engage with society, , a lit fest which is shorn of corporate sponsorship or other oppressive forms.