Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s works have remained a hot favourite with Indian filmmakers. His novels have been translated into all major Indian language. What is it that makes him so popular even now, decades after his novels were first published? Is he different from other Indian writers in some way? Or, does his fiction lend itself better to the language of cinema? What makes his works attractive to both Indian filmmakers and to the Indian audience?

By the time this article is published, one more film based on Chattopadhyay’s Devdas will be ready for release. Called Daas Dev, this adaptation is directed by Sudhir Mishra, who has given us some iconic films like Dharavi, Yeh Wo Manzil To Nahin, and Main Zinda Hoon. Of course, he has also made Chameli and Yeh Saali Zindagi, which were poles apart from his earlier films. This is possibly the 17th or 18th film inspired by Devdas. In fact, even Pakistan has its own film based on Devdas, made in 1965!

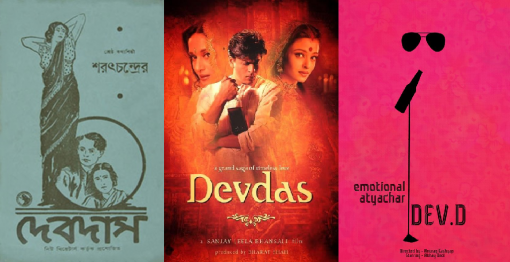

The famous Bengali novel, originally published in 1917, began its celluloid journey from the silent era in 1928. Three of its most memorable celluloid adaptations were the two by Pramathesh Chandra Barua, in Bengali (in 1935) and Hindi (in 1936), for New Theatres; and Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955) featuring Dilip Kumar, Vyjayantimala and Suchitra Sen. All three films had a beautiful musical score that remained faithful to the original novel.

The 1935 Devdas, produced by New Theatres, remains an all-time favourite. It made Barua (1903-1951) an overnight star and revolutionalised the way cinema was perceived. It was no longer just about entertainment. Now, cinema could be used for social concern and to express literature on celluloid. Chattopadhyay, who was a frequent visitor of the New Theatres studio in south Calcutta at the time, said to Barua after seeing Devdas,

“It appears that I was born to write Devdas because you were born to recreate it in cinema.”

It is rare to hear such praise from a writer. Over time, the character of Devdas became synonymous with the name of Barua. Till today, the image of Barua, the man, is inseparable from the image of Devdas, the character he played.

Though he mostly adhered to the original script, Pramathesh used Chattopadhyay’s novel as raw material, giving it his own structure and transforming what was purely textual into an essentially visual form. Avoiding stereotype and melodrama, Barua turned the film into a noble tragedy. The film’s characters are not simply black and white, heroes and villains. They are ordinary people trapped within a rigid and crumbling social system. Even the lead character, Devdas, has no heroic characteristics. What one sees are his weaknesses, his narcissism, and his humanity, as he is torn by driving passion and inner conflict. Devdas established Barua as a front-rank filmmaker and New Theatres as a major studio.

Both Pramathesh and K L Saigal, who played the lead in the Hindi adaption, turned into cult figures after Devdas became a hit. The character of Devdas and the eponymous film became “a reference-point in the romantic genre.” Never before had an Indian film won such commercial and critical acclaim. The Bombay Chronicle hailed it as “a brilliant contribution to the Indian film industry. One wonders as one sees it, when shall we have such another.” It ran to packed houses in all the major cities, with people returning to see it over and over again. A Bengali magazine wrote, “Pramathesh Barua, who became famous overnight with his superb direction of Devdas, shows in this picture the same skill in handling psychological themes.”

The climax of the film was Barua’s original contribution to the story; it differed from the ending Chattopadhyay had written. Had Devdas, the film, ended the way the novel did, the audience might not have understood it. In the film, Barua decided that when Paro (Parvati) hears that Devdas is dying under a tree outside her house, she runs out to see him. But, as she rushes towards the gates, they close in on her. The imposing gates of the house were a metaphor for the social taboo against a married woman rushing out to see her former lover, crossing the threshold of her marital home. It was unthinkable in those days. “Barua conceptualised this entire scene. It was not there in the novel. When Sarat Babu saw the film, he was so moved that he told Barua that even he had never thought of ending the novel the way Barua had done,” Jamuna Barua, who played Paro in both the adaptations, recollected.

Barua did not create Devdas, he was Devdas.

So powerful was the impact of Pramathesh’s portrayal on screen, so close it grew to his private life, that, to the Bengali audience, Devdas was synonymous with the actor who played the character. By the time the film was released, Pramathesh became aware that he had contacted tuberculosis, and, drawn inescapably to the bottle like his onscreen self, slowly wasted away, coming to an untimely end barely 15 years after he had breathed life into the character of Devdas on screen.

The social relevance of Barua’s Devdas lies in that it was the first film to place on celluloid the social ramifications of a man of high birth who moves away from his feudal, upper-caste, and upper-class roots in rural Bengal to the colonial city of Calcutta before World War II. It tried to explore the inner pain of this man, torn between the pull he feels towards his village and his wish to run away to the city to escape from the tragic reality of a lost love. His wilful move towards self-destruction could be read as his casual indifference to the village that he once belonged to, a village he now responds to with mixed feelings. Before his death, he tries in vain to run away from an anonymous death in the unfeeling city by coming back to the village in one last desperate attempt to renew his lost ties. The harsh, heartless reality of the city has changed his perspective towards the village. He finally rejects the tempting illusions and fantasies that the city once held for him. The city loses Devdas but the village, too, refuses to accept him even in his death, ignominious, humiliating, and tragic as it is. Only two women, Paro and Chandramukhi, who operate like invisible, unwritten “guardians of conscience” in the wreckage that his life is reduced to, are left to grieve over his death.

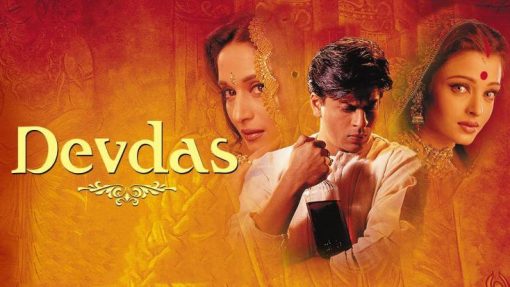

Another adaptation, much discussed and debated in recent times, is Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas (2002). This is the version most young viewers are familiar with. With its bright colours, loud music, unending songs, and exaggerated melodrama, the movie ends up projecting a hysterical — rather than failed — masculinity. It doesn’t do justice to the original story, failing to show what makes this story so popular, so well loved.

On 23 May, 2002, Bhansali’s Devdas was premiered in an out-of-competition section at the Cannes Film Festival. According to Trade Guide’s Taran Adarsh, of the 120 Hindi films released till then, 119 had lost their money. Devdas was as big a gamble because its production costs were enormous by the standards of the time. Today, Bhansali’s version is remembered only as a spectacular extravaganza that draws from the grandeur of historical films like Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeeza. Bhansali relinquished Chattopadhyay’s stark, understated narrative and replaced it with an opulence seldom seen before in Bollywood cinema. It made generous use of the latest technology, enhanced lighting, and sophisticated camera movements. In some senses, Bhansali went completely overboard with the original story, almost scandalising those who were familiar with earlier versions of the film by Bimal Roy and Barua. He introduced a jugalbandi dance sequence between Paro and Chandramukhi; he modified the character of Paro’s mother, distorting it beyond recognition. The most “innovative” tweak, though, was that his Devdas (played by Shah Rukh Khan) went to Oxford for higher education! Thank our stars that Bansali did not shoot Devdas in Oxford!

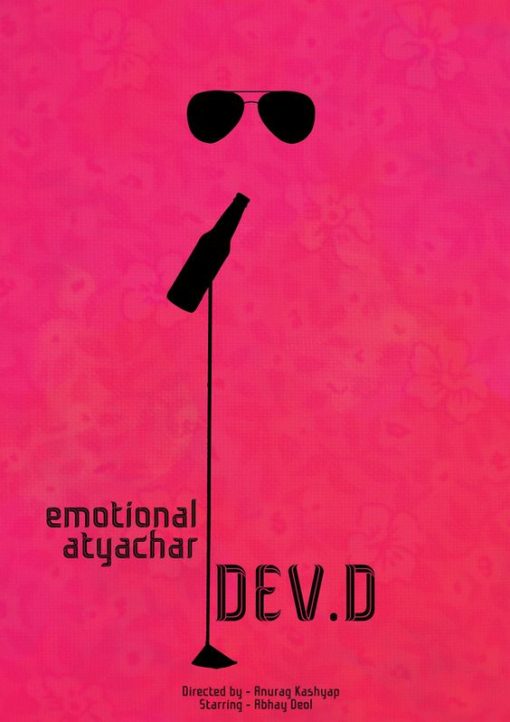

But the two films that ran completely off the mark from the original story (a love triangle that ended in tragedy) are Anurag Kashyap’s Dev. D and Sudhir Mishra’s soon-to-release Daas Dev. This, perhaps, is also evident from title of the two films, both of which tweak the original. In his paper, “Love’s Labour’s Not Lost – 21st Century Reincarnation of Devdas,” Santanu Mandal, a research scholar, offers a brilliant and imaginative reading of Anurag Kashyap’s Dev. D, which was markedly different from Chattopadhyay’s Devdas.

Mandal’s reading of the original Devdas and Anurag Kashyap’s Dev. D are radically different from conventional readings of the other Devdas films. The core of Devdas, Mandal insists, is the absence of a mature sexuality and the failure to consummate love. Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas clings to his childhood myth of love, rejecting the adult love of both Paro and Chandramukhi. In one melodramatic scene, he even hits Paro with a fishing rod, not as an expression of his macho muscle power, of which he evidently has none, but in a typical act of impotence. His failure punishes the two women. Paro remains a virgin even after marriage.

There is some ambiguity about Paro’s visit to Devdas’s room in the night, when he comes back to the village on hearing of his father’s demise. Paro, by that time, is already married. However, there is no direct reference or suggestion of anything sexual or even elementarily physical, such as a kiss or an embrace. Chandramukhi is constantly subjected to his verbal abuse and humiliation, through which he tries to maintain or even increase the social, cultural and educational distance between them. Instead of being repulsed, this pulls her even more towards him. She voluntarily retires from being a prostitute to embrace life as a reformed courtesan. Devdas converts both the women into maternal figures as one finds them tending to him in sickness, indulging him like a naughty child.

Dev. D captures the milieu of wealthy, business class, patriarchal, Punjabi families of Chandigarh. Dev, or Devendra Singh Dhillon, is the son of a rich Punjabi businessman, who was sent to London when he was very young. But the seeds of love had already been sown between him and his father’s business manager’s daughter Paro, or Parminder Kuldeep Singh. While away, their love only grew, slowly edging out the young innocent infatuation and giving way to more concrete sexual demands. Dev finally comes home for his brother Dwij’s wedding. Their obsession with intimacy is arrogantly complacent. Interestingly, Paro is more interested and aggressive in wanting to consummate their love, portrayed tellingly when she carries a mattress on her bicycle pillion for a literal “roll in the hay.” But Dev misunderstands her advances, his fickleness revealed from his faith in gossip and hearsay. The bubbling love gives way to misunderstandings, which end with Dev rejecting Paro and leaving. In retaliation, the aggressive and sensual Paro agrees to be married off to a wealthy businessman, a widower with two children, a match arranged by her father. Her decision is based on compromise and convenience, and Paro puts marriage before sexual gratification.

According to Mandal,

Despite its highly sexed-up and drugged-up representation of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas, Kashyap’s film captures the essence of the original character accurately. The representation throws up the image of a weak, snivelling, self-destructive individual with a morbid fascination for emotional and masochistic cruelty. He always realises the worth of something after he has lost it. The film reaches beyond the period element of the original text by focussing on the immediate reality of a society in transition. Anurag Kashyap makes this possible on cinema by adapting the myth of Devdas and transforming most of its elements to present day scenarios while preserving its true spirit. The lovers, for example, behave like the youth of today, engaging in whispered intimacies [over] the phone. The intimate conversations are soaked in direct sexual innuendo as much as the censors will permit, salacious, unclean and with video clips of Paro in the nude sent as attachments on the e-mail that Dev can watch across distant lands.i

Mishra’s Daas Dev is an exploration of power and how it gets in the way of love. He presents Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas’s tale in reverse. Mishra’s Dev does manage to break free from his addiction and the dynastic ambitions of his family in the end. Neither does Paro stay locked behind the imposing gate of her husband’s house. As for Chandni — is she a money handler, fixer, manipulator, or simply a girl in love? The trailer is somewhat vague and confusing but, perhaps, this has been done by design to pique the audience’ curiosity.

About the film, Mishra says,

The thought for this film arose when Pritish Nandy asked for an adaptation of Devdas. It struck me that Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Chattopadhyay’s Devdas were similar. I found that Paro and Devdas were connected through their respective families which brought in the class difference. I wrote in Paro’s father as Dev’s father’s political secretary. The separation between Paro and Dev becomes political. After Dev’ father dies, there is a rift between the two families. When Paro emerges from their section of the mansion, it is as Dev’s political rival. My story actually begins after the original story of Devdas ends. It is a modern day story. There is class distinction structured into the story and there are political schisms within love. So, Daas Dev.

The conjecture around the success of the novel’s translation into English, by Sreejata Guha, first published in 2002, is quite strange. Looking back, Devdas, the character, is a failure in life, in love, and within his family. He is a bad son who is “whitewashed” by the author when he gives his share of the inheritance to his mother before walking away. He does not give it out of love and duty to his mother. He does it because he has already stepped into a world where his family, including the inheritance, have become meaningless for him. Do failures in cinema and literature make great heroes for the audience and the readers? Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Othello are also failures, if looked at from a certain perspective. Yet, they are immortalised in different representations in literary criticism, drama, and cinema. The two women in Devdas’s life are stronger, more confident, and powerful than Devdas could ever hope to be. They make their choices when they have to and, as much as possible, live life on their own terms. Not so, Devdas. He harbours a narcissistic, tempestuous love, he wallows in self-pity; his ego hurt by his father’s rejection and Paro’s marriage to a kind zamindar whose old age guarantees that her virginity remains intact. He makes alcohol his wife, his mistress, and his companion, in life and in death.

Chattopadhyay’s works have a sense of timelessness, a universality, that make them both cinema-friendly and topical for filmmakers. Directors’ never cease to be fascinated by this author. The audience never fails to be trapped by its transient hypnosis. The social and domestic ambience in his novels may belong to days long past, but the story, the romance of his characters, the fluid and dramatic changes in their relationships with each other, continue to hold the reader and the audience in a trance, never mind any question of credibility or logic that they might raise.

i. Mandal, Santanu: ‘Love’s Labour’s Not Lost – 21st Century Reincarnation of Devdas,’ paper presented at International Conference on Literature and Bollywood films organised by Viswa Bharati University’s Department of English and Other Foreign Languages on March 13, 2011.