“I am a little unconvinced with the last line.”

“Which one?”

“Here. It says that Lenin is an important figure for the workers and peasants in India. I wonder if there is any empirical proof ,” said a translator and editor I was about to interview. He was referring to an article we had published after the visuals of Lenin’s statues being razed down in Belonia, Tripura, had been circulated a day or two before. It made some people debate, wonder, and argue about a man who died almost a century ago.

We continued with the interview. The question fell through the cracks, but kept nagging me. I decided to make a few stops to find some answers.

This article is not an empirical answer to the rather straightforward question my interviee asked. It is a meek attempt to read Lenin’s works in this context.

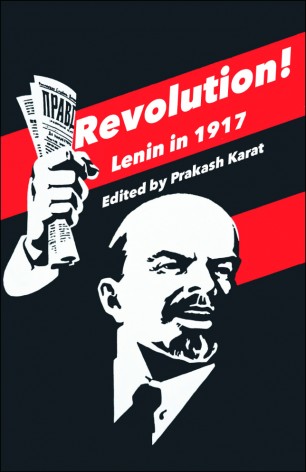

I set out by re-reading a LeftWord title brought out in 2017, Lenin in 1917! It is a collection of Lenin’s writings from February to November, 1917 — the year of the Russian Revolution.

It is edited and introduced by Prakash Karat, the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and director of LeftWord books.

I met him at the A K Gopalan Bhavan in Delhi, CPI(M)’s Central Committee office. Right in front of the entrance, I was greeted with a lovely tree rising out of yellow police barricades. The entrance is manned by busts of A K Goplanan and Lenin, who stare at each other and, occasionally, get distracted when a visitor enters or leaves.

Inside, Karat greeted me in a cubicle.

“You want to know about the statue demolitions, is it?” he asked.

“More about the book and your introduction, actually. The demolition, I think, is a good pretext to bring Lenin, and the book back into the public debate,” I said.

“Yes, a BJP leader also said that the Lenin is a foreigner, so why should his statue be there in Tripura,” said Karat.

In his introduction to Lenin in 1917!, which is equally polemical and theoretical, he pre-empts some of these attacks. “The most obvious and persistent way has been to reduce Lenin to a Russian phenomenon. This was necessary to negate the universal significance of [the October Revolution],” he writes.

The Russian Revolution did have an impact in India, and, influenced many Indian revolutionary freedom fighters. Karat, quite naturally, mentions this as he speaks of the book. “Lenin was loved even outside the Communist and Marxist circles. The Russian Revolution, which he led, inspired Indian freedom fighters. They could immediately relate to what happened on November 7 in St Petersberg. They said, people have risen against imperial monarchy there, we are also fighting the British imperial monarchy [here]. One of the first poems on the Russian Revolution written in India was by the freedom fighter and Tamil poet, Subhramaniam Bharathi. From Bal Gangadhar Tilak to Bharathi, the revolutionaries who were outside the Congress fold, everyone looked up to the Russian revolution.” Indeed, they did, and the poem, translated into English by V Geeta, can be read here.

Karat continued, “After Lenin died, Bhagat Singh and his comrades had a hearing on Lenin’s birthday. Collectively, they sent a telegram to Russia through the courts, because they knew that the jail authorities would stop such a telegram.”

The telegram was sent to the Third International. It said, “On Lenin Day we send hearty greetings to all who are doing something for carrying forward the ideas of the great Lenin. We wish success to the great experiment Russia is carrying out. We join our voice to that of the nternational working class movement. The proletariat will win. Capitalism will be defeated. Death to Imperialism.”

Vijay Prashad, the Chief Editor of LeftWord books, also emphasised some of these points over an email interview: “It was the confidence of the Bolsheviks that pushed the national movements from India to China to make much more aggressive demands for freedom. Lenin should be a national hero in India. His aggressive anti-colonialism inspired not only Indian Communists, but also Indian nationalists, as I show in my book, Red Star Over the Third World.”

“Gandhi was inspired by Lenin. Tilak was inspired by Lenin. In fact, Lenin defended Tilak. It was Lenin was wrote, in the context of the imprisonment of Tilak, that the ‘British empire is doomed’ for having awoken mass struggles against it.”

It is not that the Indian revolutionaries and freedom fighters wanted to replicate the Russian Revolution because they were in awe of it. The shared a common ideological ground, and it was Lenin who articulated this in his writings. Karat writes in his introduction, “Lenin, unlike most European Marxists, was able to grasp the true significance of the national and colonial question. In formulating the Marxist stand on the national question in tsarist Russia, he also established the connection between the working class movements in the advance capitalist countries, and the anti-colonial struggles and national liberation movements in the colonies. Both were linked by their common struggle against imperialism and capitalism.”

Image courtesy LeftWord Books

Image courtesy LeftWord Books

Lenin, living in exile at the time of the February Revolution, wrote at a furious rate until the revolution in October. The editors at LeftWord books provide excellent footnotes that put Lenin’s writings in their specific contexts. The first section of the book contains letters Lenin wrote from Switzerland, written after the tsar was overthrown in Russia and a provisional government formed. The letters were published in the newspaper Pravda. “The press is now the main thing,” he wrote to Alexandra Kollontai, who forwarded the first two letters to Petrograd in Russia.

Lenin’s copious writings show that his involvement in the revolution was a well thought out move. The revolution was not just a spontaneous uprising. It was planned. Prashad says, “Lenin demonstrated the importance of a vanguard party, a revolutionary party and of the need for decisive action when necessary. If there is no revolutionary party, there is a tendency for the most reactionary forces to prevail during a crisis. Rosa Luxemburg’s slogan is apposite — Socialism or Barbarism. Socialism does not arrive on its own. It requires a revolutionary party to provide shape to mass upsurges. That is what Lenin proves.”

Karat hastens to mention that Lenin went against the grain at the time and reconstituted Marxist theory. He quotes Lenin’s famous words from What is to be Done? in his introduction as well as in his conversation with me, “Without a revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement,” and goes on to add,

“He was relentless as far as theory was concerned. He went against the German Social Democrats, who were like the big dadas of Marxist theory if you like. But when the movement went into action, he would break the theoritical barriers. It happened again and again in 1917. His theory was never very rigid; it was flexible. He also quotes one line quite frequently — I can’t exactly remember who’s written it — ‘Theory is grey, and practice green’. ”

But what was the purpose behind looking at what Lenin wrote in 1917 now, one hundred years later? Karat says, “1917 was the year in which Lenin could combine theory and practice, and modify his theory based on what he learnt in practice. If you see that as the revolutionary praxis, then, in the 21st century, we have to constantly relook at theory, renew it. You will find yourself in situations where, in your own country or society, you have to constantly update and revise your theory and practice.”

But has that happened in India? Lenin’s statue was brought down after the Left front lost the elections in Tripura, a state which had voted them back to power five times, where it had formed the government for 25 years. Karat concedes, but not in relation to the situation in Tripura. He asks himself, “Are we coping with the tremendous changes in the society today, say, in terms of the advances in science and technology?” He then goes on to answer his own question,

“There is a very valid argument that Marxist theory has fallen behind in coming to grips with major changes and transformations. The practice, the forms of struggle, the movements, they too have fallen behind. It’s not changed or innovated itself. ”

Indeed, for Prashad, the need to relook and reread Lenin can only be more urgent in a time like this. He says in his e-mail, “Today, there is disorientation in the Left. There are many who believe that there is no need for such a party, that spontaneous action is enough to defeat reaction. We Marxists believe that this is a surrender to the forces of reaction.”

There can be no doubt that Lenin’s persuasiveness can be matched by very few writers. Towards the end of the book, when he urges everyone to not wait, to join the uprising, one can almost hear his appeals as if they were are being made today. In a letter to his comrades, written on 17 October, 1917, he is almost worried of the time lost in taking his words to print: “We are living in a time that is so critical, events are moving at such incredible speed that a publicist, placed by the will of fate somewhat aside from the mainstream of history, constantly runs the risk either of being late or proving uninformed, especially if some time elapses before his writings appear in print.” In another letter to the Central Committee members on October 24, 1917, he is aware that he is creating history: “History will not forgive revolutionaries for procrastinating when they could be victorious today (and they certainly will be victorious today), while they risk losing much tomorrow; in fact, they risk losing everything.”

Karat’s steady but quavering voice in his Delhi office is quite naturally far removed from the force of Lenin’s language. But he, too, is hopeful, “It’s a very complex situation now, but there are rich possibilities.” Indeed, Prashad reckons, “We want to return to Lenin, to revisit Lenin, to recount the Leninist moment in order to steel ourselves for the fights against fascism and towards a socialist society.”

I step out of the office to brace the afternoon heat that will only make life harder. The tree still seems to rise out of the barricades, but it provides the right amount of shade for the CRPF personnel boxed inside with a rifle in front of the office.

I try and look for the line that the Karat quoted out of memory on my phone. It was a modification of the German poet and philosopher, Goethe’s lines, “All theory, dear friend, is grey. But the golden tree of actual life springs ever green.”

I move out of the shade, Lenin still in my bag.