“I can hear around me the question as to why I stopped writing. I had to end my career because of a strong and ceaseless inner voice telling me that I have written whatever I had to write in this life and if I write again I will just be repeating what I have already written. An artist should never accept the fate of a bullock going round and round an oil-press. And no one else can share or resolve the dilemmas in a writer’s creative life”

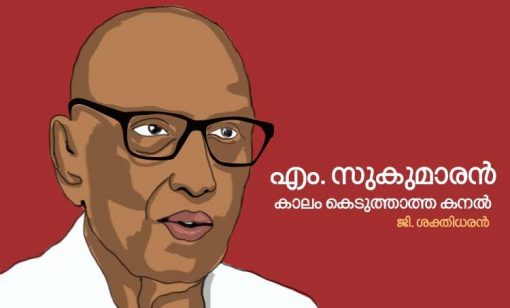

These were M Sukumaran’s words on why he left writing. He announced his death as a writer 24 years before he passed away this year. He had had a writer’s block earlier too: he did not write anything for a decade after 1982. He did write briefly in 1992 and ‘94 but embraced silence once again till he passed away a few days ago.

The statement I have quoted was from a letter he sent to some of his old colleagues. However, it came from a writer who, along with a few others like Pattathuvila Karunakaran, U P Jayaraj and P K Nanu, had radicalised the art of fiction, particularly short story writing in the 1970s. Sukumaran was also a trade union leader and an activist while he was working at the Kerala Accountant General’s office in Trivandrum. He was dismissed from service during the Emergency on flimsy “political grounds”. The statement might sound paradoxical because it came from such a writer, but no one can deny the honesty and the poignancy behind them.

It was not that he did not get any recognition. He had a committed readership. Critics wrote about his fiction (though not very frequently). His stories were turned into screenplays for two acclaimed films. He was also awarded by the state and the national academies of literature. He won many other prizes and recognitions, but he would hardly flaunt them. He was an unlikely combination of an activist and an introvert.

Born in Chittur in the Palakkad district of Kerala in 1943, four years before India gained independence from the British. Sukumaran began writing stories of solitude and suffering. This was common among many modernist writers in the 1960s, but he caught the people’s attention primarily after his stories were picked up by M T Vasudevan Nair, a veteran writer and then editor of Mathrubhumi Weekly. These stories were different from his earlier stories as well as the mainstream modernist fiction in general. He politicalised the existing modern sensibility by interrogating the status quo.

For him, the status quoists were not just the landlords and capitalists and their political representatives, but also the existing communist parties that he — like many young intellectuals and writers at that time in places like Kerala and Bengal — thought had moved away from the common people and were centred around the middle class.

All critics of the established Left at the time were labelled “Naxalites” and Sukumaran was no exception. He, however, never took part in the Naxalite movement. We can see the works of the writers of the 70s with more clarity now. A few decades since break-down of that movement has given us enough distance for it. These works upheld the principles of social justice and the struggle for equality, in whatever form. Many of the writers of the 70s continue to write or edit journals even today without the backing of any political party or without aligning themselves with any ideology and uphold the same values in their life as well as writing. Many who used to be activists went on to join various movements for social reform. Some have become feminist activists. Some of them are environmentalists. There are others who are online journalists. Still others who are Ambedkarites. Some have even become Gandhians who have rediscovered and reconstructed Gandhi from a subaltern perspective.

While Sukumaran was a close observer of these changes — and even a sympathetic observer, as is evident in one of his last interviews, which he seldom gave anyway — he also felt that he had nothing new to say. He left writing and activism altogether, though his name continues to come up in any discussion of modern fiction in Malayalam, especially political fiction.

Sukumaran’s stories were different from those of the other radical fiction writers who had emerged in the 70s in at least two ways.

First: he invented a form of fiction in Malayalam that can be called “political allegory” and practised it with a unique craftsmanship. Second: as a keen observer of international and national politics, he was aware of the gradual drying up of his sources of hope and dared to express this awareness sharply but subtly in his stories and short novels. He critiqued the gradual moral decadence and ideological shifts of the communist parties, mainly in USSR and China but also in India through stories like “Ayal Rajavu” (The King of the Neighbourhood), “Vellezhuttu” (Cataract), “Sheshakriya” (The Last Rites) and “Pitrutarpanam” (Obeisance to the Father). At the same time he never gave up hope. Till his last breath he believed in the possible resurrection of the Left in India in some form. He went on dreaming of an ideal Left free from the many ills that plague the existing one. He shared the faith that common people and party workers at the lowest level still have in the parties. He had probably seen flashes of that ideal at work in individuals like P Krishna Pillai, A K Gopalan, and Varghese in Kerala who represented the spirit of the early phases of both the CPI and CPI (ML).

I had been a regular reader of his stories ever since they began appearing in Mathrubhumi Weekly. But I started reading them closely, however, when he insisted that I write an introduction to his collected stories. It was an honour for a younger contemporary to be given this opportunity. I felt the same joy that I had felt when other elders and contemporaries like Kamala Das, Pattathuvila Karunakaran, and Sara Joseph had invited me to introduce their selections, or when I was asked by publishers, editors, and organisers to write studies or deliver talks on Balamani Amma, Vaikom Mohammed Basheer, Lalitambka Antarjanam, M T Vasudevan Nair, and O V Vijayan.

But Sukumarn’s invitation was the most unexpected of them all. Before that, we had never met and corresponded very rarely with each other.

Of course, we admired each other’s work, which was expressed in casual articles or conversations. I met the author at his home in Trivandrum many years later, when he was unwell. He did not go to receive the Sahitya Akademi award he was given. He was indifferent towards such recognition. However, he did not officially decline them. It is well known that when his old colleagues at his office wanted to organise a reception for him when he won the award, he sent them a letter. It said, “I like a seat among the crowd where no one notices me. I find it difficult to put on the robe of an award–winner. I would then sweat, feel choked” He used to say that he did not became a communist by memorising the theories of Das Capital or statements from The Communist Manifesto. The hungry lives of intense labour among the persecuted and marginalised ignited the ash-laden sparks of oppressive inequality he had experienced as a child. He observed these lives carefully. This, and the provocative environment of his office, is what made him turn to communism. In the same letter, he had said, that human values were becoming more transient, “political illusionists were growing like Goliath,” and “the lords of theory were dancing blissfully to the tune of the colourful spectacle of capital.” He continued, “I find servitude unbecoming of me. A hero’s death is not for me either. I find my joy now in the bliss of solitude… Even in this state, the war-cries of those who’re fighting,, the dead bodies that are scattered on the battle-ground, and the sight of starving refugees running for shelter, all these make me uneasy. I can never say that egalitarian thoughts have become outdated. Theories always win, praxis loses; and yet the dream of a new, equal world burns in my blood like a star.”

Sukumaran was a pioneer of political modernism in Malayalam fiction. He did to fiction what some of us had done to poetry in the 70s.

He had a progressive political vision but moved away from the modes of realistic expression used by the old progressives. He had imbibed the aesthetic lessons of modernism with its penchant for stylistic and structural experimentation. He gave an intellectual dimension to short story writing without diluting the narrative like some other modernists.

His stories can be divided into four categories: lyrical-realist narratives of his early phase that introduce lonely, traumatised, and abandoned individuals feeling tormented all the time; s didactic stories, soundly grounded on the principles of class struggle written in the form of parables or allegories with an aura of the mythical around them; tales that represent contemporary political themes with an element of the magical; and, finally, psycho-analytical stories that analyse the mindsets and attitudes of the upper classes, bureaucrats, police officers, and their middle men, using the modes of dramatic monologue or the stream-of-consciousness technique. His early stories are deeply poetic, brimming with fresh metaphors, symbols and descriptions of nature. They deal with characters picked up from the working class or the lower middle classes, covering a large thematic range from sex to devotion. Many of his protagonists in these are children, or are those who suffer from some disability or the other (like disease, sterility, deafness) or are sex-workers, housemaids, orphans, abandoned old women, betrayed lovers. .But unlike the protagonists in the modernist stories of the sixties who were tormented by imagined identity crises and existential angst, his characters suffer from real sorrows. The later stories are more political, as the writer-narrator begins to diagnose the situations and discover the material reasons for their suffering — feudal and capitalist exploitation, caste or class inequality — and discover the connections between money and power, and the discourses and practices of the capital and the state. Through these allegories and modern legends, Sukumaran created counter-aesthetics reminding us of Walter Benjamin’s statement: allegorisation happens when art becomes a problem for itself. Gradually, Sukumaran moved on to a diagnostic critique of the Left, the ones who were supposed to fight these forces, their (often unconscious) distancing from the poor, the middle-class ambitions of the new leaders, and the growing bureaucracy that made a mockery of the party’s principle of democratic centralism, as had happened in Stalin’s USSR. Essentially, it was the increasing gap between theory and praxis.

Sukumaran’s long narratives, written much later, were prophetic interventions dealing with the weakening of the opposition due to internal and external reasons, as well as the consolidation of the opportunistic right wing politics.

Some of his characters mark the end of an era of hope and the beginning of the ascendancy of the new muscle-men politicians who sow communal hatred among the people and reap its benefits. Two such characters come to mind. Kunhayyappan from Shehshakriya (The Last Rites) and Sreekumara Menon from Pitrutarpanam (Obeisance to the Father). The former is a sincere party worker who is ostracised by the Party, and the latter is- an old revolutionary who has a daughter who fails to understand him. She thinks her father is mad, with the father commiting suicide in the end, declaring that he is completely “normal.” . Perhaps today we can liken Sukumaran’s fictional world to that of Franz Kafka’s, whose ominous intimations and symbolic import could be deconstructed and expounded only by Marxist critics and writers like Ernst Fischer, Bertolt Brecht, Ernst Bloch, and Walter Benjamin.