My relationship with the Kenyan writer, Ngugi wa Thiongo — who is now in exile in the US — spans over three decades and is worth recapitulating to make sense of the reader-writer association. My first acquaintance with his writing; my first letter to him and his hand-written response; my first meeting with him; his connections with the places and people I love; further correspondence with him in email and in person – all have a dramatic element to them.

The first time I heard Ngugi’s name has a particular memorable characteristic. It was amidst several dramatic events. The famous Naxalite leader, Kondapalli Seetaramaiah, escaped from Osmania General Hospital, where he was under treatment as a prisoner, in January 1984. Consequentlt, there was a persecution of, and onslaught on, Naxalite sympathisers, mass organisations, and offices in Hyderabad. The then general secretary of the Radical Students Union (RSU), who was also the editor of its monthly organ, Radical March, was forced to go on exile. Later, I became associated with the journal. At the time, I was a member of RSU as a student of Osmania University, and was just thinking of leaving my MA to join a mainstream daily newspaper. Since the editor of Radical March, Dr M F Gopinath, a student of Osmania Medical College (the same hospital from which Seetaramaiah had escaped), had to go underground to avoid arrest, the RSU leadership asked me to take charge of the journal as working editor; consequently, my name started appearing from the February 1984 issue onwards.

As a result, I was completely cut off from the social circles of other students and trainee journalists, secluded in a den to read, write, and edit the news organ of the Radical Students Union. Within two months of this seclusion, by the summer of 1984, I fell into severe depression, and was almost on the verge of suicide. My friend, Mallojula Koteswar Rao, who would later become famous as Kishenji, was the then secretary of Andhra Pradesh State Committee of the Communist Party of India Marxist Leninist’s (CPI-ML) Peoples War.

He came to know of my condition and sent a friend of his, L S N Murty — editor of Kranti, the fortnightly media organ of the AP State Committee of the Peoples War — to pull me out of depression and cheer me up. And he did just that, quite literally! L S N dragged me out of my “dungeon,” where I’d been holed up so far, and took me to the pleasant green environs of Indira Park in Hyderabad. He gave me a thorough counseling for a couple of hours, recommending some readings he considered helpful, and gave me a copy of Devil on the Cross (1981-82), a novel by Ngugi wa Thiong’o. That was the first time I had ever heard the writer’s name.

The novel completely transformed me, infused enormous optimism into me, and reaffirmed my commitment to the people’s movements and life. The book indeed mesmerised me so much that I immediately wrote a 20 page letter to a friend, sharing my excitement about the book.

I shared my copy, already tattered, with all those to whom I had recommended the book. One of them was Varavara Rao, my maternal uncle. Due to other pressing preoccupations, he could not read it immediately. It was a year later, when he was in jail, that he finally read it.

Around the same time, K G Kannabiran, the famous civil liberties lawyer, also sent his copy of Ngugi’s Detained – A Writer’s Prison Diary (1981) to Varavara Rao. In prison, Varavara Rao not only found time to read and fall in love with Ngugi, but also set about translating both the books into Telugu. In every mulaaqat, he would update me about the progress of the translation, often asking me the meanings of the Gikuyu and Swahili words that used to be sprinkled in the original books. I got in touch with some Kenyan students in Hyderabad to to help him with the translations.

In the midst of reading, discussing, and thinking about Ngugi, I wrote a letter to him in March 1987, without knowing where he lived and what he did. I sent the letter to him, addressing to his publisher’s office in London, since all the books I had read till then were published by Heinemann’s as part of their African Writers Series. About a year later, in January 1988, I got a handwritten response from Ngugi.

In the next three years, I devoured all his writings – novels such as Weep Not Child (1964), The River Between (1965), A Grain of Wheat (1967), and Petals of Blood (1977); plays such as Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976) and I will Marry When I Want (1977); and some literary criticism – getting them by hook or crook. In those days, there was no internet, no facility for online purchase of books; one had to be content with whatever was available in one’s provincial town bookstore. But I tried my hand at libraries, NRI friends, and occasional visitors from foreign countries. That’s how I got Ngugi’s sixth novel, Matigari (1986). A friend from the Revolutionary Writers’ Association (Virasam) got it on his trip when he went to London on an official training. I immediately wanted to translate it.

By that time, Varavara Rao had also come out of jail, so we began editing and preparing press copies of both the translations. Mattikaalla Maharakshasi (Clay-footed Monster) was the name given by the translator to Devil on the Cross. It was published by Swechchasahiti, a small publication house set up by a group of like-minded people, one of whom was me. The book came out in late 1991 and was released in a Virasam conference in Guntur in January 1992. I had the privilege of releasing and speaking about the first book of Ngugi, ever, to be translated into Telugu.

The next book of Ngugi’s that was translated into Telugu was Detained. Written by the writer in a high security prison in Kenya, it was translated by another writer in another prison in Hyderabad.

Called Bandee (Detained), this, too, was published by Swechchasahiti and released in a Virasam conference in Hyderabad in January 1996. By that time, Varavara Rao and G N Saibaba were also in contact with Ngugi, and invited him to participate in an international seminar on the question of nationality. It was organised by the All India People’s Resistance Forum, and scheduled to be held in Delhi in February 1996.

Ngugi, along with his companion Njeeri, arrived at the seminar a day late due to visa problems, but enthralled the audience with two rousing presentations – “Nationality Question in Africa” and “Decolonising the Means of Imagination” (both included in Symphony of Freedom – Papers on Nationality Question, AIPRF, Hyderabad, 1996). In his introductory remarks at the seminar, talking about his association with India, he mentioned the letter I had written to him some eight years ago.

After the seminar, he also visited Hyderabad and Warangal, addressed a couple of meetings organised by Virasam; he visited Osmania University, Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, and Kakatiya University.

He visited Husnabad in Karimnagar district to see a massive martyrs’ memorial, built to pay homage to revolutionary activists killed by the state. The huge, 88 feet high Husnabad Martyrs Memorial was a tribute to all the activists killed in the district and had been built by family members of martyrs, with the help of people.

Despite many obstacles by the state forces, the memorial column was unveiled on 25 October, 1990 to a massive gathering. The state forces finally allowed the meeting to go smoothly in a trade-off after three government officials were kept hostage by the Peoples War guerrillas. The giant structure had become a place of interest, and Ngugi wanted to see that.

He spent some time there, noting how, back in Kenya, they did not even have a chance to remember their martyrs, let alone build a huge memorial column like this one. Unfortunately, in 1999, barely three years after his visit, the Andhra Pradesh police brought down the column with dynamites!

Charged with excitement on seeing my favourite author in person and getting the opportunity to spend a couple of days with him, I asked the person in charge of the arts and literary page of The Economic Times (where I was working at that time) whether I could write a piece on him. Thanking me for introducing such a great writer, she gave me full page to write about Ngugi.

The Economic Times’ Gallery page, on 3 March, 1996, carried four different write-ups – a half page introductory article, two excerpts from his writings, and a timeline of his life and work. That was, perhaps, the first newspaper page devoted to him in India.

Carrying on with our earlier work, we went ahead with the translation of Matigari by Vyoma in late 1996, published by Swechchasahiti, as always. It was released at a Virasam meeting in January 1997, with Varavara Rao presenting the book.

Then came the age of the internet, bringing with it a widened scope for interactions.

When the Revolutionary Writers’ Association was banned in 2005, I wrote an essay in the Economic and Political Weekly. I sent the essay, along with the information of Varavara Rao’s imprisonment in a Hyderabad jail, to Ngugi. He responded, “When you see your uncle, please pass my regards and tell him the Gikuyu proverb that there is no night that does not end with dawn!”

Around this time, Penguin proposed to bring out Varavarao’s earlier prison writings, Captive Imagination; Rao wanted Ngugi to write a preface to the book. Ngugi readily accepted.

Later, I got a chance to go to the United States in 2008. Besides seeing Chicago’s Hay Market (which gave birth to May Day) and the Monthly Review office, meeting Ngugi was one of my most preferred engagements. By that time he was a professor at University of California at Irvine. I was in Berkeley. With the help of some friends in Los Angeles, I was able to go to Irvine and spend a couple of hours with the great writer. Besides three hours of interesting and inspiring conversation covering his own works, people’s movements, and literary craftsmanship, Ngugi took me, and an accompanying friend, to Chakra, an Indian restaurant, to give us a treat. I had already read Wizard of the Crow (2006), his latest novel at the time, in a library in Berkeley.

He gave me a signed, hard bound copy of the novel for Varavara Rao, whom he fondly refers to as his younger brother, as he is two years elder. He gave me the same novel, in paperback, quipping, “Since your uncle is older, this big book is for him. For you, the smaller one!” Before he signed my copy of the book, he asked me what my name meant — flute player . When I told him, he signed off the book with the quote, “To the flute player of the movement.”

In December 2013, we heard that Ngugi was coming to Mysore University for a seminar. We tried to organise a lecture in Hyderabad too. Recently, a foundation set up in memory of the poet-singer-performer of the Telangana Peasant Armed Struggle (1946-51), Suddala Hanumanthu, had instituted an award and wanted to present its first award to Ngugi. However, because of some visa issues, he could not come. So, we held a meeting to discuss his works instead.

Then came his third memoir, In the House of the Interpreter: A Memoir (2012). With speculation of him getting Nobel Prize in Literature rising, I decided to write a piece on him.

Then, as an under trial prisoner in Anda Cell of Nagpur prison, G N Saibaba translated Ngugi’s memoir, Dreams in a Time of War (2009), into Telugu.

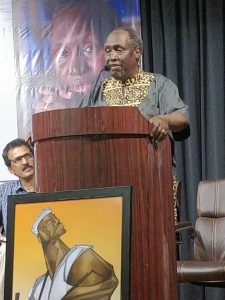

I wrote to Ngugi, requesting him to write a preface to this Telugu translation. He immediately sent a brief but powerful note covering his personal acquaintance with Saibaba and with life in prison. Saibaba was released on bail for a few months, only to be put back in jail on a life-term. In the light of all these events, we were in a hurry to publish this translation, and wanted to invite Ngugi to its release. Luckily, Seagull Books, as part of its promotion tour for Ngugi’s Secure the Base, which they had published, organised meetings in Kolkata, Bengaluru, and New Delhi. Malupu Books, which published Saibaba’s translation, managed to get Ngugi to come to Hyderabad for a day. Aas before, I got the opportunity to spend about twenty hours with him, besides accompanying him to various meeting and indulging in hours of interesting conversation.

Ever since I first read Devil on the Cross three decades ago, Ngugi, the writer, has been flowing in my veins. I began the introduction to my book, Understanding Maoists – Notes of a Participant Observer from Andhra Pradesh, (Setu Prakashani, Kolkata, 2013) with Ngugi’s words:

A revolutionary character in Wizard of the Crow, an epic novel by the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiongo, put it beautifully when he said that everybody in this society has “right to take and duty to give.” As a participant observer of the most historic and momentous revolutionary people’s movement in my native land, Andhra Pradesh, for the last four decades, I have exercised my right to take to a large extent, and this part-fulfillment of my duty to give is, in a way, a humble and modest repayment.