Why do mainstream and off-mainstream filmmakers have this tendency to use big metros as the settings of their films? We don’t have to seek far for the reasons. One, it is easier to shoot the film in Mumbai specially because the industry itself is centered around this city; two, all big metros fit neatly into the glamour, the chutzpah, the noise, the sound, and the loudness of colour, texture, characterisation, and add to the box office possibilities of a said film; three, big cities offer a vicarious escape route for small town and rural audiences, which can fantasise itself in cities that it has never visited and may never have the chance to visit. At the most, Bollywood cinema has extended its parameters to a Goan setting, or the more picturesque places like Gulmarg, Pehelgam, Shimla, and Kulu-Manali. Or, if the budget is big enough, it could be London, Switzerland, or the US.

In recent years, this has changed with both small and big banner filmmakers opting to position their films in small towns and villages that we did not imagine being linked to Bollywood cinema. Filmmakers are now opting to place their story, plot, theme and characters against the backdrop of a smaller town. The rural-urban divide now stands blurred because of the invasion of the small town film between these two cliché-ridden polarities. Amir Khan’s Dangal, for instance, was shot for around two months in different places of Ludhiana, apart from the little-known villages of Kila Raipur, Gujjarwal, and Narangwal.

The small town story began much earlier. Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975) is set in a fictitious small village called Ramgarh and, interestingly, offers two very radical representations of women in the film, underscoring that small town and village women, fictitious or real, need not be underestimated on any count. Sippy took pains to design distinctly different speech patterns to suit the different characters in this film. Speech counterpoints were established through the two major female characters, one extremely talkative and the other totally silent, investing the film with an unusual richness.

Arjun Appadurai1 has written about ethnoscapes (spaces produced by the inflow of people such as immigrants, refugees, etc.) technoscapes (inflow of technology, etc.), finanscapes (flow of global capital, commodities, etc.), mediascapes (the repertoires of images and information), and ideoscapes (ideological shifts connected to Western world views). These are different ways of looking at the global cultural flows strongly influenced by perspective, overlapping, and the rapidly shifting instability and mutability of global cultural flows.

But, Madhuja Mukherjee2 adds, it is also important to study the cityscape or the structural changes that occur when immigration happens, or the physical shifts that take place (with globalisation of the economy and the culture) when flyovers, multi-storied buildings, or shopping malls are built by doing away with the existing habitat of the original residents—old houses, parks, water bodies, etc. Or, when neon signs, digital bill boards are erected like patchworks in the blue sky. Suddenly, the familiar spaces, the narrow lanes and by-lanes, the grocer’s shop across the road, the old house built by one’s ancestors, etc, are practically devoured by other geometric structures that invest the city with a kind of socio-political rebirth born out of the “scapes” described by Appadurai. The nostalgia is tempered with a sense of history. This applies to all the metro cities in India. But what about small towns?

Small town settings have changed the mindset and the landscape of Bollywood cinema. Dedh Ishqiya was aesthetically shot in Lucknow. The place was perfect for capturing the Urdu dominated cultural reflections of the characters in the film. This film brought back India into the mainstream Bollywood scene as filmmakers and goers were pleasantly surprised at the way this place was mapped across the film.

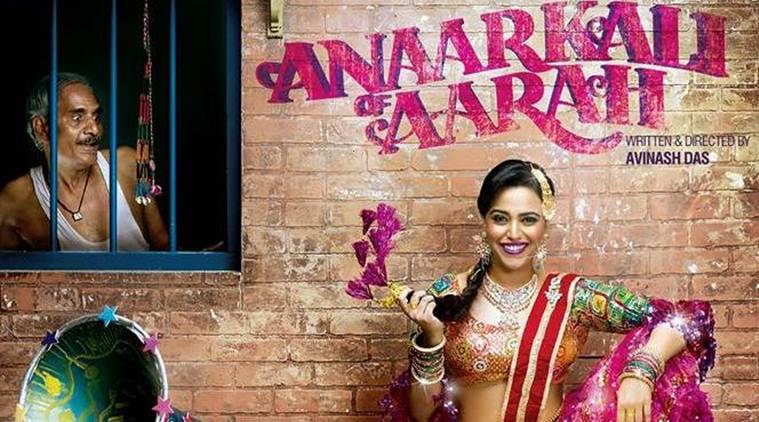

Arrah is a little known district of Bihar. Anarkali of Arrah pushes the borders of performance and genre to tell the story of a gutsy woman called Anarkali, an erotic stage dancer who belongs to Arrah district but performs wherever the price is good. She tries her best to live life on her own terms and is not ready to sleep for money if she does not want to. The film did not do too well commercially, but it will be remembered for its wonderful performances and the aggressive storytelling. Few of us not belonging to Bihar would have heard of Arrah before this film. It dispels many myths about small town lifestyles and also the conceptions that big town people have about small town women. Lipstick Under My Burkha was set in Bhopal, capturing the skycape dotted with the domes of masjids, jostling against colourful bazaars with beauty parlours hiding in a small by-lanes, and a large house filled with tenants gossiping, squabbling and so on.

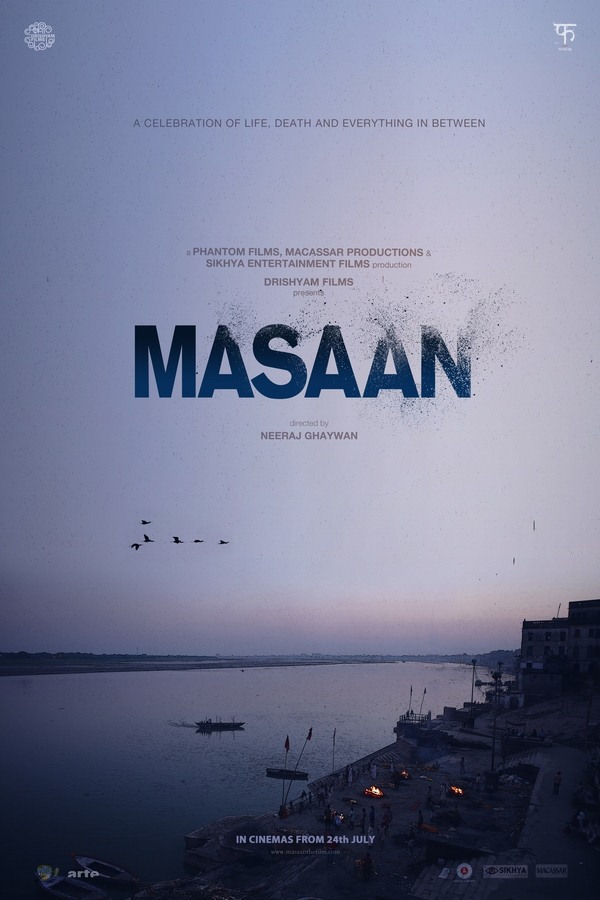

Talking of women, a recent film to project the blending of the tradition and the modern among young girls and women in terms of values on life, love, and sex in a small town like Benares has been brought forth in Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan (2015). One of the two young women in the film, Devi (Richa Chadda), who teaches computers in a class, decides to have sex with a young boy from the class in a hotel room. Devi does not think she has done anything wrong. Masaan captures the evolution of this historic city, a place of worship for the Hindus, from the ancient times to the modern, and what the youth of the city hanker for and chase. The holy river Ganges. that flows along the city, carrying with it the flowers and corpses of the dead, is also a centre of action, as are the streets, the computer classes, the internet cafes. Popular music and shairis recorded and played over and over on cell-phones, food stalls and festivals where young boys and girls exchange shy glances, all these things mark the blend of the traditional and the modern. The film could not have been shot in any other Indian city.

In his well-researched paper, ‘Provincialising Bollywood? Cultural economy of north-Indian small-town nostalgia in the Indian multiplex’, Akshaya Kumar states, “The small-town may have gradually become more form than content, it might have also become the anchor of a cinema located elsewhere—which would mean a body of films that shun the label ‘Bombay Cinema’.” He adds that Dabangg re-establishes the tricky but magnetic relationship between Bollywood and the small-towns of north India, yet not without a critical take on them. It illustrates an enthralling performance that borrows from the tradition of spoof as much as it does from impersonation. All the women in Dabangg, from Chulbul Pandey’s mother to his wife, and the other item girl, are any day bolder and brasher than their big city counterparts.

Bareilly Ki Barfi is set in the north Indian town of Bareilly. This backdrop crosses the barriers of big city romances and introduces us to real people with real stammers, real crushes and real go-betweens to make it a delightful Bareilly romance. It also shows leading ladies as aggressive, smart. and bold enough to try and lead life and make love on their own terms, belying the “cute and shy” myth of the small town girl once and for all. The common thread that binds these two films, apart from the small-town ambience, is Ayushmann Khurrana, who projects the image of a small-town boy with conviction.

Shubh Mangal Saavdhan is set mainly in the city of Haridwar with its colour, its bustle, its music and dance, and its temples. But it deals with the rather delicate subject of “erectile dysfunction,” showing that the size, fame, or affluence of a given town has nothing to do with the boldness of a subject that has never been dealt with in Bollywood before.

Paan Singh Tomar is a fictionalized account of a world class athlete who ruled the steeplechase event (a 3,000 meter obstacle race that includes a water jump) at the National Games seven years in a row (his record stood unbeaten for ten years). He was later forced to become a dacoit. The film was shot in Dholpur, between Agra and Gwalior. It is on the extreme eastern fringes, along the border between Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. Some of it was also shot in Bhind, near Chambal in Madhya Pradesh, where Paan Sing Tomar lived.

Amit V. Masurkar’s Newton has been almost entirely shot in the Dandakaranya forests in Chhatisgarh, notorious for the dreaded Maoists/ Naxalites of the region, which has also led to the region being referred to as India’s “Red Corridor.” These are areas populated mainly by adivasis, who are victims of the greatest poverty, illiteracy, and overpopulation in modern India. Swapnil S. Sonawane, as DOP, offers a model lesson on how a film with a high political note shot entirely in the forests of Dandakaranya should be picturised on low key, with muted colours dominated by ambers and siennas and browns, very few close-ups, with the camera playing magic all the way, capturing incredibly beautiful frames from beginning to end.

Sharat Katariya’s Dum Lagake Haisha is the first ever Bollywood film to have been shot entirely in Haridwar. The film is an endearing story of Prem and his oversized wife Sandhya, who struggles to find love and acceptance but staunchly refuses to go on a diet, so as to become slim, just to make the marriage work! Finally, Prem surrenders to her size and the marriage has a happy ending. The film turned out to be a sleeper hit, like most films shot in small towns.

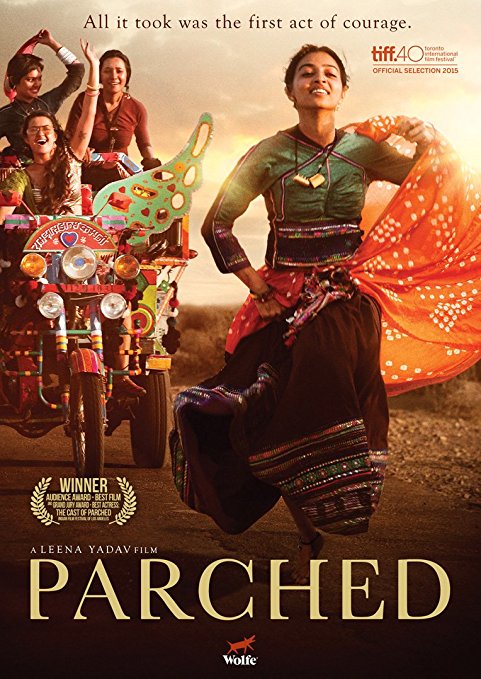

The colours of Rajasthan are captured beautifully in Leena Yadav’s Parched, as seen in the lighting of the tent with the dance shows, the décor of the huts, the red chillies spread out to dry in the sun, juxtaposed against the dark interiors of the cave and the shimmering waters of a small water space. Parched throws up an outstanding and unconventional vision of the sex-starved lives of three young women and one adolescent girl, across age, occupation, and courage or the lack of it. These colourful women derive vicarious thrill by talking sex in their own way, in their own language, and laughing at their own jokes. It debunks the myth about unlettered women of the village being naïve and simple.

The choice of Vadodara (formerly Baroda) invests Amir Khan’s Secret Superstar with an old-world charm, with the school children seeming more like real children, unlike the sophisticated, over smart, headphone-sticking, selfie-clicking, star crazy teenagers one gets to witness in films placed in large metros like Mumbai, Delhi, or Bangalore. Vadodara has a significant Muslim population and is the third largest city in Gujarat. The school environment is immune to any communal shades or colours and is just like a school should be, with students preening in their school uniforms, pulling each other’s leg, and yet being sympathetic to the issues that their friends may be facing. Insiya’s clear disinterest in academics or any kind of school work is natural and convincing for the dreams she nurtures. Take a bow, small towns with wonderful storylines. Bollywood and its audience love you.

1. Appadurai, Arjun: Modernity at Large : Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

2. Mukherjee, Madhuja: “The City in Cinema, and Cinemas in the City: South City Mall and Locations of Display”, Silhouette, Vol.VIII, 2010. p.94.