This essay was first published in The Afternoon Despatch and Courier through the Associated Press Features on 18 December, 1992, nearly twenty five years ago in the aftermath of the planned demolition of Babri Masjid. The Indian Cultural Forum is grateful to the author for sending us the hard copy of the article in print and for granting us permission to republish it here.

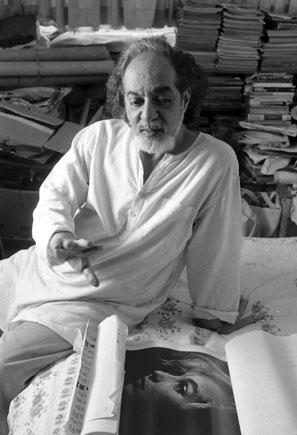

About 15 years ago, the Gujarati poet Adil Mansoori decided to quit India and try his luck in the United States. The reason he gave was that he could no longer stand being discriminated against as a Muslim in India. I don’t know if another poet, Saleem Peeradina, has decided to stay on in the US for the same reason; he hasn’t said so. But it wouldn’t surprise me if that reason was at least partly responsible for his decision. The painter Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh has spoken openly about the difficulties he and his family faced when trying to find accommodation in the Hindu quarter of Baroda.

Moving to another country doesn’t necessarily mean the problem of discrimination won’t occur all over again. Mansoor and Peeradina may just have swapped one kind of discrimination for another. It should also be obvious to all of us, though it seems to be obvious only to some, that communal prejudice and hatred doesn’t cut only one way in India – against non-Hindus. The feeling of hostility against the outsider, the “other” is widespread enough (as we know from current events in Bosnia and Somalia), ready to spring out of us at any given moment. Given the right mix of personal fury and circumstance, the beast will attack as it did at Ayodhya. The greatest injustice we do to ourselves and the society we live in is to believe it doesn’t exist.

India’s ruling elite has been guilty of that injustice more than any other group I know of. It has both created the myth of Indian (more specifically Hindu) tolerance and given it such wide currency that it takes an event like Ayodhya to shock us out of our sleep. In fact, to narrow the focus even more specifically, tolerance doesn’t need the label of Hindu, Muslim or that of any other religion to be attached to it. Without being a religion in itself, it exists among the mass of under-privileged people in a way we scarcely try to understand. They tolerate us; we don’t tolerate them. Without that tolerance where will our fine homes be? When theirs get too close to ours, we move heaven and earth to get them demolished. Scarcely a hairsbreadth of emotion stirs in us when we get the job done. But when they start a demolition job you can be sure their emotions are fully engaged. You have been recognised, in all your fulsome splendour, as the outsider, the “other”, the person from another class. The beast has attacked.

Literature which doesn’t recognise the beast is a literature of dangerous escapism and on that count many writers, even the most revered ones, have been and are dangerously escapist. The beast, which is just another term for uncontrollable violence, was certainly recognised by George Orwell. He also faced it personally during his police officer days in Burma and as a volunteer fighting in Spain. But even he hasn’t escaped the charge of being escapist. His essay “Outside the Whale” has been attacked by Salman Rushdie for advocating literature’s retreat from politics, when, Rushdie argues, literature should embrace it.

I don’t necessarily agree with Rushdie or accept his charge against Orwell but that is certainly what Rushdie has attempted in his novels, and it’s one of the most difficult things to do. A convincing portrayal of the beast in politics and working on a mass scale, as in Ayodhya, is hard to come by. Most writers restrict it to the domestic arena and I think it’s a perfectly legitimate thing to do since domestic violence, family realities of oppression and discrimination, don’t necessarily exclude the political. The theatre has attracted some of the best writers in this field: Ibsen, Strindberg, Eugene O’ Neill and in India Vijay Tendulkar, Mahesh Eklunchwar and Gieve Patel, to name a few.

But there’s a source beyond these writers, one which they drank from and, in doing so, saw the beast in its first terrible splendour. That source is Greek Tragedy, something that didn’t nurture Indian theatre for millennia, until the moderns came along. It isn’t my business here to ask why Sanskrit theatre avoids tragedy and whether it’s the absence of the very concept of dramatic tragedy, such as the Greeks had, that leads us to very real tragedies again and again and so inexorably throughout our history. The ruins of our monuments, which we’re so proud of, are obviously incapable of teaching us anything. The tragedy of partition has exorcised nothing. For the work of tragedy, in Aristotle’s definition, is to exorcise, “by means of pity and terror”, to bring about “the catharsis of such emotion”.

Just before Ayodhya, the BBC correspondent in Sarajevo said that it felt as though a grim tragedy was being enacted in the city, with UN personnel as mute spectators to the show. Now we’ve had our own show. Not everyone is mute, certainly not those who have lost their dear ones. Where I write from, in Bombay, I do not hear their wails. But I hear others. The moon is being eclipsed and I hear people in the streets crying for alms so that the demon lets go of that ball in its mouth. We, the educated, the children of Nehru’s “scientific temper”, of course know better: the ball will be freed whether we give alms or not. But for once let’s be honest and say our science has failed us, our education has failed us and will continue to fail us again and again until we recognise that however many books we read and however many alms we give, there’s a demon that won’t let go of our hearts. The beast is always there and writers are always there to recognise it. One kind of tragedy takes place when they don’t, another kind when they do. The first kind leads to the carnage in Ayodhya and after. The second kind leads to a carnage of our negative emotions, including, temporarily, an elimination of the beast.

Anyone who has experienced the power of great tragedy, whether enacted on stage, seen on the screen or in the pages of a book, knows that it’s a healing power, restoring us to ourselves. It puts us in our place in a universe which may, finally, be absurd, as the existentialists claimed. It hardly matters if it is or it isn’t. Great tragedy subsumes us in a universe in which there are more things than are dreamt of in certain philosophies – whether they be the narrowly scientific ones on which we were brought up or superstitious fundamentalist ones which are threatening to swallow up even the educated now.

It may be naïve to think that dramatic tragedy, attempted by our best writers, is one thing that will bring us to our senses now. We’ve had too little of it and maybe it’s too late to hope for it now. If that is the case, the fire next time will be here to stay, as will the beast with our hearts in its mouth.

Also read:

Remembering the Bombay Riots Part II: The Story of Teacher, Journalist Firoz Ashraf by Meena Menon

Remembering the Bombay Riots Part I by Meena Menon

The Fallout of the Planned Demolition of Babri Masjid: Analysing the Violence in 1992-93 by Ram Puniyani

What Our Self-Declared Nationalists (Read the Hindu Right) Owe to British Historians for their Claims on Babri Masjid or Ram Temple by Souradeep Roy