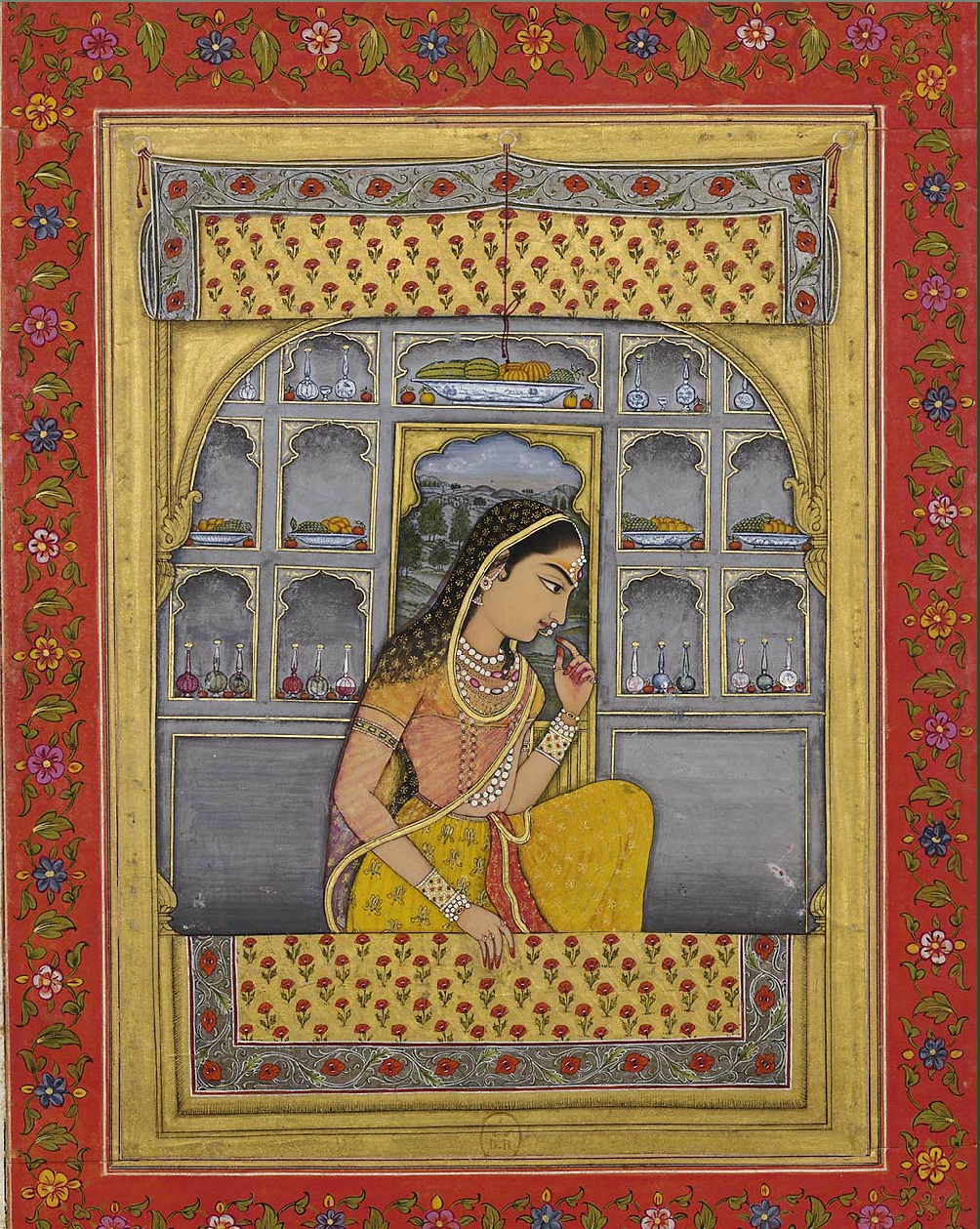

An 18th century painting of Padmavati / Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

An 18th century painting of Padmavati / Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

In his review of R.S. Rosenstone’s History on Film/Film on History, Professor James Chapman, University of Leicester, writes, “The historical film has been analysed for its mobilisation of the past for propaganda, for its role in the emergence of national cinemas, and for its contested place in ‘taste wars’ between the views of middle-brow critics on the one hand and the popular preferences of cinema audiences on the other. Another tradition, arising initially from France and subsequently taken up by US scholars in the 1990s, has focused less on context and more on the structural and ideological features of film.”

Sadly, there has been little historical research available on Indian cinema or film studies done on historical films. The rate of illiteracy and the degree of complete ignorance of the people who create a ruckus on the basis of fictionalised history on cinema, therefore, have no logical reason to vent their anger against this or that film just on the basis of the said film being a corruption of history and for casting a smear on historical characters that are said to have been rooted in their ethnic and cultural history. Yet, there has been no dearth of costume dramas filled with colour, glamour, chutzpah, and magical music within Indian cinema, which the filmmakers pass off as “historical films.”

Till date, there have been only a few honest attempts at creating the genre of historical films. That is, if we don’t take into account the kind of films that are steeped in controversy even before their release—with the media going completely crazy in an attempt to grab both eyeballs and space—much to the secret joy of the filmmaker concerned, who is then confident that his film will bring in the money, and more, within the first week of its release. Among the former are films like Pukar (1939), Sikdandar (1941), Prithivi Vallabh (1943), all of which have been made by Sohrab Modi, who had single-handedly created a new demand for historical films. All these films were box office hits. But the same director’s Jhansi Ki Rani (1952) turned out to be a dismal failure, though it was officially the first Technicolor film to be shot in India. Historical films or romantic fantasies—dripping with glamour, grand sets, costumes, and song and dance—have been a special genre in Indian mainstream cinema.

The history of the “historical” film, or the romantic stories draped in, so-called history (or pegged to mythical stories woven around history), began much earlier. Before sound stepped into cinema, Mughal historical films like Kalyan Khajina (1924), or heroic tales from Rajasthan about Rani Padmini called Sati Padmini (1924), were hits not only in India but also in England. This was evidenced by the fact that Sati Padmini won a certificate at the Wembley Exhibition the same year, as pointed out by Andrew Grant in his work on the historical genre in Bollywood cinema.

Abdur Rahman Chughtai’s paiting of Anarkali / Image Courtesy: Pinterest

Abdur Rahman Chughtai’s paiting of Anarkali / Image Courtesy: Pinterest

The two most famous films based on the same historical romance between Salim (who would later go by the name of Jehangir) and Anarkali, namely Anarkali (1953) and Mughal-e-Azam (1960), are considered fictions because Anarkali was a fictional character and did not exist. Noted art historian R Nath has argued that Jehangir had no wife called Anarkali for whom he would have built a tomb. There is no evidence that Prince Salim ever fell in love with a courtesan, and there is no reference to her in Salim’s autobiography. Regardless of whether Anarkali is purely fictional or based on historical fact, her legend has continued to mesmerise the people of South Asia for ages. She has caught the eye of nearly every big name in the arts in South Asia for the past 100 years. Anarkali and Mughal-e-Azam were major hits in both Pakistan and India. Playwright Syed Imitaz Ali Taj’s version for the stage is considered a masterpiece. Abdur Rehman Chughtai’s depiction of Anarkali—incidentally, this was also used as cover art for Taj’s play—is one of the most famous paintings of the courtesan. But, according to historians and historical fact, she did not exist, ever.

Filmmaker Ketan Mehta did not think twice before putting in entirely fictionalised love stories in his film Mangal Pandey: The Rising (2005). Mangal Pandey, the eponymous protagonist of the movie, was a Sepoy in a regiment of the British East India Company. His actions helped spark the Indian rebellion of 1857. But the two romantic sub plots—the first is between the British Commanding Officer William Gordon and Jwala, a teenaged widow he saves from being burnt as Sati; the second is the romance between Mangal Pandey and Hira, whom he marries before being executed— were pure fiction. The film made decent business but faced controversy. The Bharatiya Janata Party demanded a ban on the film, accusing it of showing falsehood and of “character assassination” of Mangal Pandey. Samajwadi Party leader Uday Pratap Singh called on the Rajya Sabha to ban the film for its “inaccurate portrayal” of Pandey. Protestors in Ballia district, where Pandey had lived, damaged a shop selling cassettes and CDs of the film, stalled a goods train on its way to Chapra (Bihar), and staged a sit-in on the Ballia-Barriya highway. But the film continued to run and made reasonable business.

Santosh Sivan’s Asoka (2001) flopped because, halfway through, Shahrukh Khan (who was playing Samrat Asoka) seemed to forget that he was playing a king and went back to being Shahrukh Khan, mannerisms and all. Besides, all the characters (from the Mauryan Empire and Kalinga) spoke modern Hindi, as opposed to the ancient Prakrit dialects spoken in the 3rd century BC. The names of the historical figures in the film were also changed in accordance with modern Hindi. There is no historical evidence of a queen ruling Kalinga at the time of Asoka’s invasion. Plus, the whole Pawan/Kaurwaki episode was pure fantasy. Asked how much liberty he took with history, Sivan said, “We had to dramatise to show the magnitude of the change (in Asoka) and also to create an impact. We basically followed his life but we added characters and created dramatic moments.” If that be so, why call it a historical film and not a feature film adapted from history?

A descendant of Peshwa Bajirao-I alleged that historical facts were “altered” while portraying the late king and his wives, Kashibai and Mastani, in Bajirao Mastaani. A petition was filed stating that the song ‘Pinga’ is offensive to Marathi culture. A descendant of queen Kashibai Peshwa, who wished not to be named, claimed that Kashibai suffered from an arthritis-like ailment at a very young age and was bed-ridden for most of her life. She also suffered from asthma, and hence it was impossible that she danced with Mastani.

Bajirao Mastaani raises questions on whether historical romances are based on truth or are they a form of romanticising history. The commercial risks are underscored by their box office success. The question is not so much about the commercial success or failure of historical romances but more about the extent to which such films, one, reflect the historical conditions and contexts of these romances; two, how much they are based on authentic sources; and, three, whether they are a part of what has come to be termed “contextual film history.”

The overarching question that arises is that if one were to go deeper into so-called historical films within Indian cinema, one would only uncover the falsity that hides under the glamour and chutzpah of so-called “history.” Eminent historian, professor emeritus in Aligarh Muslim University, and former chairman of Indian Council of Historical Research, S. Irfan Habib claims that Rami Padmavati was not a historical figure and there is no record of her before 1540. According to Habib, the queen was a fictional character created in the poem Padmavat, written by Malik Mohd Jayasi in 1540. The poem traces the story of Padmini, Alauddin Khilji, and Rawal Ratan Singh, and has no basis in fact. Some believe that Amir Khusrao referred to a beautiful queen of the Padmini class in his epic work Khazain-ul-Futuh, but there is no proof. The words he uses in the story about Allauddin Khilji being the “Solomon of this Age” are, however, taken from this work.

Habib further insists that there was no historical character named Jodha Bai, as shown in Jodha-Akbar, directed by Ashutosh Gowarikar. It is true that Akbar married Amber king Raja Bharmal’s eldest daughter, but her name is not mentioned anywhere. There is no mention of her even in Jehangir’s hmemoirs, Tuzuk-i-Jahangir. According to N R Farooqi, Head of the Department of History at Allahabad University, “Jodha was not Akbar’s wife but Jahangir’s and she was Shahjahan’s mother!” It is said that Gowarikar hired a research team of historians and scholars from New Delhi, Lucknow, Agra, and Jaipur to guide him and help keep the film historically accurate. However, how can any accuracy, historical or otherwise, be sought in a love story rooted in fiction?

We had never heard of the Karni Sena till they decided to destroy everything to do with the film Padmavati in a misguided attempt to protect their “culture” and “history,” in ways that were extremely anti-cultural and ahistorical. One wishes that people of the Karni Sena would have read up on authentic history, so as to be able to justify their keenness “to protect the lineage of their ancestors from any misrepresentation”, before they wreaked violence. Threatening to cut off the actress’ nose or kill the director are more violent and aggressive than the violence Khilji is reported to have been notorious for!

If at least one among them had gone through historical documents, or consulted a history teacher, they would have discovered that Rani Padmini or Padmavati is not mentioned in any Rajput or Sultanate annals, and there is absolutely no historical evidence that she existed. Here are some historical facts that reduce all the violence by the Karni Sena, and their ‘brothers-in-arms”, to a rude joke: Allauddin Khilji lived between 1296 and 1316, whereas Padmini is mentioned in Malik’s poem in 1540 and wonder of wonders, the legendary mirror that the Padmini-Allaudin Khilji story so famously describes, couldn’t have existed because mirrors, as we know them now, were invented in Germany in 1835 by German chemist Justus von Liebig.

So, what “history” is one talking about?