I was preparing to leave Bangalore for three weeks when I got a call from a friend in Mumbai asking me to switch on the TV immediately, saying that Gauri had been shot. I though Gauri had gone driving off on one of her trips and been shot at. She had always received threats since the time she took over Lankesh Patrike. Within minutes of the news of her death, people from all over were sending messages and calling. Many of my friends, who had met her at my place, were also devastated. By the time we rushed to her house, journalists and other people had already reached, and a crowd began to gather. In the sleepless nights after that evening, an absurd thought ocurred again and again—of Gauri sitting at her desk at the office that night before the edition and calling out, ‘Stop press! Gauri Lankesh has just been killed, we have to cover that!’

Neither her family nor her friends had expected such a great public outpouring of grief and anger at her death, that she would become a global icon of resistance. We had not thought that she was so powerful. With us, she was more vulnerable, speaking of her struggles and always good for an argument or a joke. We used to pop into each other’s houses when we were depressed, to unwind. She could be brutally frank.

Gauri lived two streets away from my place, in a house built by her mother Indira, an astute businesswoman who owned a popular saree shop which had supported the family in lean times. Though we both grew up in Basavangudi in South Bangalore, we only met when I moved into my newly built studio in Rajarajeshwari Nagar in 1996, after twenty years of having been away from the city. But I had known her father, P. Lankesh, since the early 1970s when, as a silly teenager just out of school, I used to hang around Central College with a disreputable bunch of older friends known as the ‘Chod’ gang. The English department was famous. It had professors like the influential intellectual T.G. Vaidyanathan and P. Lankesh, the celebrated Navya (Modernist) Kannada writer, each with adoring groups around them. Later becoming a new wave filmmaker himself, Lankesh had played the role of the rebel Brahmin Naranappa in the first Kannada new wave film Samskara, directed by Pattabhirama Reddy and based on the novel by U.R. Ananthamurthy, with Girish Karnad playing the good Brahmin. It was a strong critique of caste, particularly dealing with the hypocrisy of the influential Madhwa Brahmin community (to which my family belongs). Though the censors had initially banned Samskara, the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting had revoked the ban. I do not remember much of a commotion from the Brahmin community when it was released in 1970. My mother and her friends went off to see the film with a naughty air. I even acted in a play directed by Lankesh which had been staged in the Town Hall. It was the Kannada translation of Aristophanes Lysistrata, a comedy about a woman, Lysistrata, who persuades the Greek women to boycott sex with their men to force them to end the Pelopponesian War. A family friend, member of the Swatantra party, wrote a strong letter to the Deccan Herald that the play was obscene. Though I was only in the crowd scenes, my father was furious and that was the end of my theatrical career!

Lankesh left his job and started the first Kannada tabloid Lankesh Patrike in 1980, against the disapproval of his literary friends who thought it would vulgarize his writing. He was probably inspired by the popular success of his political column in the Kannada newspaper Prajavani. Lankesh was a Lohiaite influenced by the charismatic Karnataka socialist leader Shanthaveri Gopala Gowda . I think his decision came out of a desire to ‘go to the people’ after the tumultuous days of the 1970s, a decade marked by widespread movements for social justice and protests against the Emergency. Bangalore was the hub of the influential Navya literary movement, new wave cinema and new theatre dealing with social issues. Prasanna had founded the left theatre group Samudaya just before the Emergency which had been doing political theatre all over Karnataka. The local paper Deccan Herald had also become a leading opposition after K.N. Harikumar came back from JNU and took over as editor in 1978. The actress Snehalatha Reddy, socialist and wife of Pattabhi Rama Reddy, who had played Naranappa’s Dalit lover Chandri in Samskara, was falsely accused in the Baroda Dynamite case and jailed and tortured during the Emergency. She died soon after being released.

Based on Gandhi’s Harijan, Lankesh Patrike was a powerful anti-establishment voice for the oppressed and marginalised which ran on readers subscriptions with a strict policy against advertisements. It grew to have a huge readership. It was a mixture of political exposes and sensational tabloid writing mixed with a strong literary content, giving a platform for new voices. What Lankesh also did was to invent a new language, or maybe many, delightfully tweaking Kannada with the fluidity of a master. Film scholar Madhav Prasad says he used to wait to see the new edition in Kolkata for the sheer pleasure of reading the language. One cover had the title “Bam Gum Yuddha’ (Bangarappa- Gundu Rao War). No one had used Kannada with such audacity.

When I moved to Rajarajeshwari Nagar, I was introduced to Gauri by our older friend and the ex-cricketer Balaji, a neighbour of the Lankeshs’. His house had served as an intellectual adda in Basavangudi where Lankesh used to go to play badminton every evening. Basavangudi was the centre of Kannada literature and theatre. The Vidyarthi Bhavan café in Gandhi Bazaar had been the meeting place for two generations of writers. Prasanna used to have a running joke that the great Kannada Navodaya (Rennaissance) writer Masti Venkatesha Iyengar was so lusty that he had not one, but ‘two-two dosas’ every day.

When I first met Gauri, she was a journalist for the Sunday magazine under Vir Sanghvi and we used to meet often. Rajarajeshwari Nagar was lonely and scarcely populated. Gauri and her filmmaker sister Kavitha used to talk in a racy, slangy Kannada that was delightfully new to me. We both had completely different sets of friends and used to throw large parties. My then husband Ashish Rajadhyaksha and our group of friends, all old Bangaloreans who had returned, had just started the Centre for the Study of Culture and Society — CSCS. Gauri had been married to journalist Chidanand Rajghatta, but they had broken up before we met. Lankesh and Ananthamurthy were the yin and yang of Navya literature and their children were good friends. But after Lankesh attacked Ananthamurthy in his paper, there was a rift. Gauri was loyal to her father and I never met the URA crowd at her place after that. I remember that, in one of her parties, I was dancing on one foot because my other leg was encased in plaster after a bad scooter accident, when Prakash Belawadi (now a leading Modi bhakt) came up to me and bemoaned that people did not use their hands to dance and demonstrated some fancy moves.

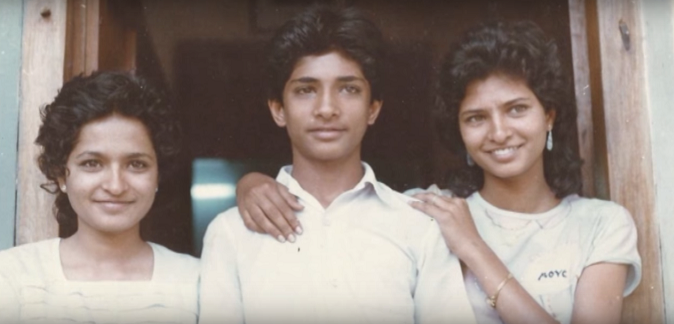

In 2000, when Lankesh suddenly died, there was a crisis and Gauri had to take over the paper as editor. The sisters adored their father. Though Kavitha had been Lankesh’s favourite and Indrajit, the youngest son, was his pet, Gauri was the only journalist in the family. She had recently moved to Delhi and was enjoying working in the new ETV channel for the first time as a television journalist. After his death, the family realised that the paper was broke and there was only a few thousand rupees—‘ just enough for his cards money’—in his bank account. Lankesh Patrike, which had a readership of two lakhs in its heyday when Lankesh was known as a kingmaker, had lost to the new era of 24/7 television. The family thought of shutting down the paper, but Gauri told me that if the paper had been shut down, the agents would not return the collections from the last issue and they would not be able to pay salaries. She chafed when her younger brother Indrajit was named proprietor, at the thought that she would have to work under him as the editor. Some years later, when they fell out over her activism, she opened her own paper, Gauri Lankesh Patrike.

Having been an English journalist, Gauri had to start from scratch and learn to think and edit and write in Kannada. She was belittled as a ‘convent educated’ English journalist who was stepping into the shoes of a legend. For some years she disappeared from her friends to immerse herself in her new world, working relentless hours, until three or four in the morning every day. In Bangalore, many of us mix English words with Kannada, and the joke is that if you add an ‘u’ sound to an English word it becomes Kannada – like table-u, chair-u. She had to stop thinking in English. Her writing would never have the literary magic of her father, but she followed his advice—that the secret of good writing was to express one’s ideas simply and honestly. She had a naughty sense of humor and a sense of the absurd. There was a lot of palace intrigue in the paper when she joined. She laughed that her appointment was similar to the young Indira Gandhi, seen as a “dumb doll” being set up as president of the Congress by the old guard who had thought that they could manipulate her. Soon many of the experienced journalists left the paper. It was tough going. Towards the end she was practically writing the whole paper herself and continuing to run it without advertisements, trying to finance it with an examination guide and publishing section. She had recently talked to a friend about going digital. No one thought that her Kannada columns would someday be translated and published as important documents as they are being done today, or that she would win a major International award.

Gauri never considered going back to a job in English journalism despite all her struggles in running the paper. She thought English journalism was frivolous and, if national, had a scattered audience. While as the editor of her own paper, she would have the freedom to take up her own causes and intensely address a local but real constituency. (In fact, recently, when she was invited to write for an English daily, her column was so hard-hitting that it was soon taken off on orders). The literary content went after a while, as that was not her forte. She soon realized that journalistic activism was not enough and she would have to plunge into activism on the ground to change things. Though her father was alsoways a benchmark, she brought in her own radical politics, contemporary feminist sensibility and subjects such as LGBT rights, to the conservative Kannada readership. And in the middle of all this, bred in a literary milieu, she was also translating fictional works and essays.

The Kannada literary and journalistic world is extremely patriarchal and dominated by male chauvinists. Gauri was a rare being who was cosmopolitan, well-travelled, and very contemporary, while being deeply rooted in the regional. She must have been one of the few women who owned and ran their own political paper with a fearless voice, not only in the state but internationally. I would put her in a long and rarely recognized tradition of activist women journal owners and writers from the early nationalist period in India, like Nanjangud Thirumalamba and Belegere Janakamma from Karnataka. Incidentally Thirumalamba’s writing was publicly dismissed by Masti Venkatesha Iyengar in an essay in the 1960s, resulting in her disappearance from the Kannada literary scene in humiliation. But Gauri was made of sterner stuff. One of our journalists wondered patronizingly why, as a woman. she did not stick to culture instead of getting into politics. He seems to have been unaware that cultural figures, from M.F. Husain to the ‘award wapsi’ writers, have been the butt of attack of our Hindutva forces. In fact, Gauri had started off at Times of India by covering the culture beat. She had several paintings in her house gifted by artists from those days. I had given her a photograph from my Phantom Lady series, which showed me jumping from a building in a masked Zorro costume. Recently, When she had called us over to meet dalit leader Jignesh Mevani, she introduced me as an artist and dragged him by the arm to show him my work on the wall. Jignesh was astonished and they both cackled with laughter.

One of the things we had discussed when we met Jignesh were the threats to Gauri’s life. I used to drop in at her office for a chat and coffee when I was in Basavangudi. Once, in the early years, she showed me a pile of postcards on her table and asked me to look at them. They were filled with filthy sexual abuse and lewd bodily descriptions. Long before the internet, the ‘chaddis’ as her father had famously named them, had discovered Gandhi’s postcard to be an invaluable tool for trolling. And postcards had no censorship. I asked her how she could work facing this abuse day after day, and she said she used to get upset at first but then decided to ignore it and not be intimidated.

As women living alone in independent houses, for some years we had a policeman on a yellow and black spotted bike from the Cheetah force checking on us every night and signing a notebook. Once, years ago, Gauri had attacked a powerful film family and received threats on the phone. Late one night, I heard some rustling sounds from the garden and found two policemen peering through the living room window like comic characters from a Master Hirannaiah play. They said they had come to warn me that they would be patrolling my house all night, asking me to not to get alarmed. At my look of surprise, they asked me if I wasn’t Kavitha Lankesh? I knew at once that they had come to protect Gauri Lankesh, only they thought I was Gauri and Gauri was Kavitha!

I had only seen bodies lying askew in a pool of blood in crime films. Dear Gauri. It is heart wrenching to think of your shock and pain. Gauri was smart, pretty, fun loving, gutsy and independent. When she threw herself into Kannada journalism, she became an indomitable activist. Towards the end, she seemed to be moving away from all the vanities, towards living an austere life. She ‘adopted’ the rising young leftist leaders like Kanhaiya Kumar, Shehla Rashid and Jignesh, pampered them and organized meetings for them in Karnataka. Film maker Anand Patwardhan questioned why she was killed now, not before or later. Everyone agrees it is because the elections are coming up. Because Gauri, being from the Lingayat community herself, strongly supported the demand for a different religion status for the Lingayats (which apparently had been researched thoroughly by Kalburgi)—a strong vote bank—and had recently published an edition covering this issue. Yet onother friend is sure that the timing was because an important leader was visiting the city at the time. Gauri, a staunch rationalist who had become a nodal point for anti-fascist activism and an influential oppositional voice, had to go.

After those initial lonely years, Rajarajeshwari Nagar had grown and several good friends—all independent, like-minded, and vocal individuals—had moved here and we had a ‘gang’. Gauri was complaining about our last meeting, saying that we went off for a night show at the local mall leaving her behind.

In our future gatherings we will deeply miss that most incorrigible member of the ‘gang’, Gauri Lankesh who—hopelessly, carelessly, tragically—got herself assassinated.

Bangalore, November 2017