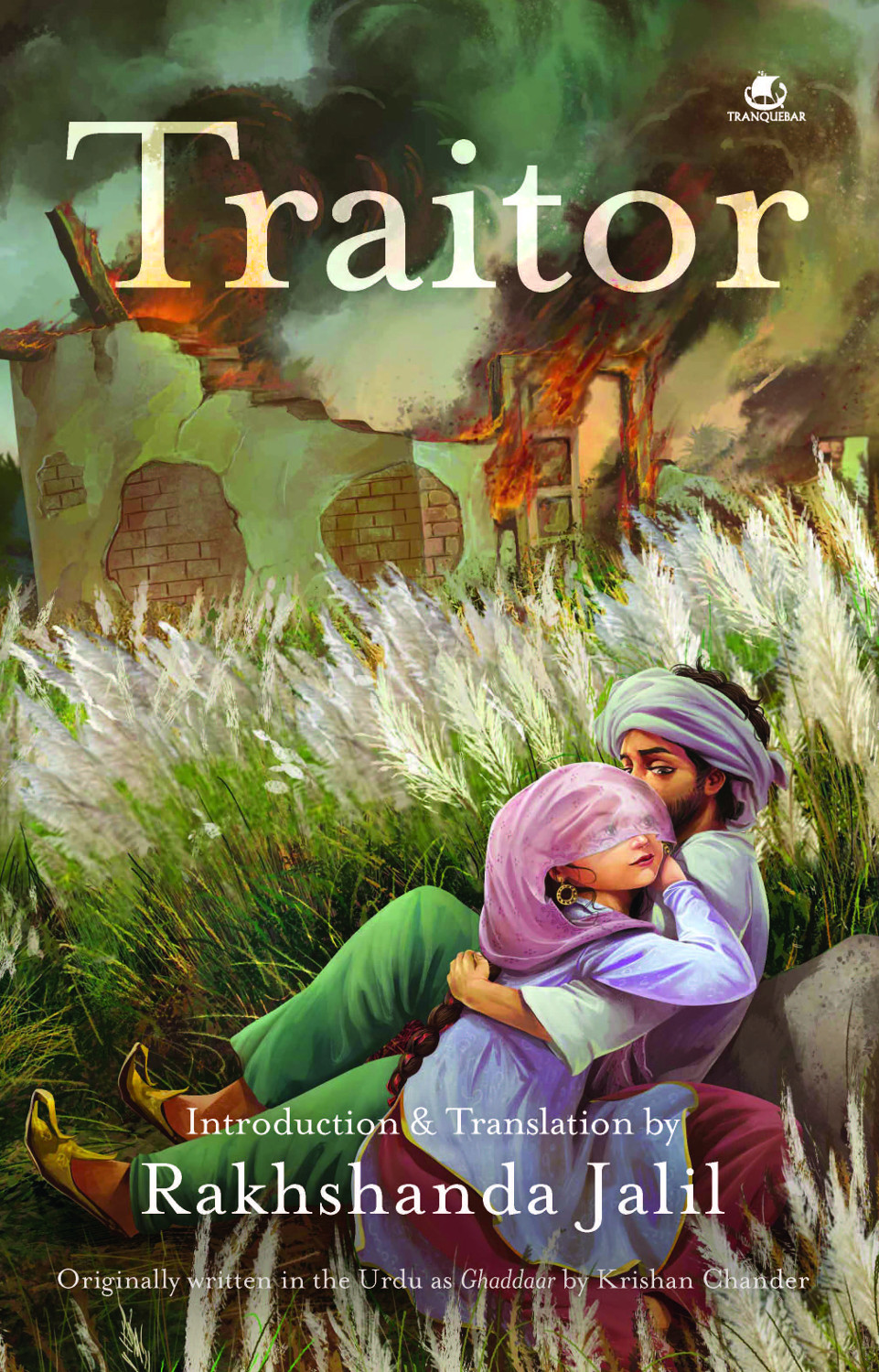

Krishan Chander’s Urdu novel, Ghaddaar, meaning ‘traitor’, begins with a delicately woven romance between an unmarried Muslim girl, and her married Hindu lover. But the world outside is being torn asunder and Krishan Chander shows how love, brotherhood and humanity swiftly turn into redundant emotions, as permanent lines are drawn between two nations.

‘Traitor’ is a word that acquires a new meaning and a sharper edge in the times we live in, Krishan Chander’s classic novel seems especially relevant as we mark the 70th anniversary of the annus horribilis that was the year 1947.

‘No monster can be more barbarous than the mob, which assumes the name and the mask of the people.’

– Cicero in ‘Dream of Scipio’

The word ‘traitor’ acquires a new meaning and a sharper edge in the deeply polarised times we live in when certain words are being high-jacked by certain persons or groups professing a certain ideology. Some words, such as ‘traitor, or ‘nationalist’ or, for that matter, even ‘secular’ have become the worst victims of the worst excesses of our times. While some words, such as ‘secular’ or ‘nationalist’, were laudatory in their original usage or at the very least benign since they had no sharp edges, are now used mockingly, hurled by one group at the other like poison-dipped darts. The scope and meaning of certain other words is being enlarged to accommodate more layers of meanings. Traitor is one such word.

Who or what is a traitor? The dictionary tells us the traitor is ‘a person who betrays someone or something, such as a friend, cause, or principle; a person who betrays a country or group of people by helping or supporting an enemy’. The synonyms listed out for it are betrayer, back-stabber, double-crosser, double-dealer, renegade, Judas, quisling, fifth columnist, viper, turncoat, defector, apostate, deserter, colluder, informer, double agent; and for more informal use, snake in the grass, two-timer, rat, scab, etc. More often than not, the traitor is within — a group, a country, a people.

The Minister for Human Resource Development, Smriti Zuben Irani, in a blistering rebuttal of the opposition’s charge that her government was bent upon muzzling dissent and clamping down on free voices in centrally-funded universities, quoted Cicero in the course of a long and impassioned speech in the Indian Parliament on 24th February 2016: ‘A nation can survive its fools, and even the ambitious. But it cannot survive treason from within. An enemy at the gates is less formidable, for he is known and carries his banner openly. But the traitor moves amongst those within the gate freely, his sly whispers rustling through all the alleys, heard in the very halls of government itself.’ This however is a paraphrasing of what Cicero actually said: ‘The only plots against us are within our own walls … the danger is within … the enemy is within…’ (M. Tullius Cicero. The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, translated by C. D. Yonge, BA, London, Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden, 1856). In truth, the quote used by Irani is, in turn, a paraphrasing from an essay by Justice Millard Caldwell of Florida: ‘A nation can survive its fools, and even the ambitious. But it cannot survive treason from within. An enemy at the gates is less formidable, for he is known and he carries his banners openly against the city. But the traitor moves among those within the gates freely, his sly whispers rustling through all the alleys, heard in the very halls of government itself. For the traitor appears no traitor; he speaks in the accents familiar to his victims, and he wears their face and their garments, and he appeals to the baseness that lies deep in the hearts of all men. He rots the soul of a nation; he works secretly and unknown in the night to undermine the pillars of a city; he infects the body politic so that it can no longer resist. A murderer is less to be feared. The traitor is the carrier of the plague.’

It is against these popular definitions of a traitor, dredged up for public consumption and lent not merely currency and urgency but also linked to a jingoistic nationalism and an adrenaline-driven idea of a nation, that Krishan Chandar’s Urdu novel Ghaddaar, meaning ‘traitor’, needs to be read to understand its full import. The times we live in make Ghaddaar an important novel and a timely one. Written sometime in 1959 and published in 1960 by Naya Idara from Delhi, it seems especially brimful with meaning and relevance as we mark the 70th anniversary of the annus horribilis that was the year 1947. That a novel ‘located’ during the awful month of August 1947 can be so real and immediate seven decades later, is both tragic and significant. Tragic because it tells us that we as a people have not changed or evolved as much as we should have in the course of seventy years of Independence, that the communal ill-will that marred our centuries-old tradition of pluralism has not entirely left our psyches as it ideally ought to have with our coming of age as a nation and as a people, that the lava of communal hatred still erupts now and again like pus from a festering wound, and that any deviation from a majoritarian discourse is still seen as a sign of betrayal, and the hyper nationalism of the mob continues to sway popular opinion. In a purely literary sense, Ghaddaar is significant because it tells us, yet again, that a truly good work of literature is one that rises above its time and circumstance and speaks to us across time and circumstance and makes common cause with its readers when it speaks of universal concerns, such as cruelty or humanism, barbarism or meanness of spirit or the human heart’s infinite capacity to love.

***

By the mid-1930s a literary movement had captured the imagination of large numbers of writers and readers across the length and breadth of India. This was the Progressive Writers’ Movement (PWM), known in Urdu as the Tarraqui Pasand Tehreek, and the literary grouping that would increasingly begin to exert influence in not just literature but in all other forms of creative expression was known as the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA), or the Anjuman Tarraqui Pasand Musannifeen. For most commentators on the literary history of India, the significance of the PWM is uncontested. Its importance lies not in the intrinsic merits of the writers associated with it or their individual works; it lies instead in the role played by the PWA from the mid-1930s till the mid-1950s in shaping the political consciousness of large numbers of people, in its unequivocal emphasis on the need for social change and in the relentless portrayal of these twin forces in their literature. The Movement and its proponents were a powerful and inescapable force. Not only did they commandeer a space for themselves on the political, social and literary canvas of India for nearly three decades, they also re-crafted the existing literary canon. In the years before Independence, they influenced the debates on imperialism and decolonisation, exploitation at home and unfairness abroad, and in the years immediately thereafter they were at the centre of the discourses on the nature of the newly-independent, post-colonised state and society. The idea of a nation, of what constitutes nationalism and national identity were of especial interest to the progressives. They responded with great alacrity to Jawaharlal Nehru’s call for all citizens to join the nation-building project. As a result, the 1950s and the early 1960s saw a great deal of literature being written on the ‘idea’ of India and what constitutes ‘Indian-ness’.

The PWM penetrated into different Indian languages, most notably Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Marathi and to some extent Telugu, Oriya and others. But it was most vibrant and vigorous in Urdu and Hindi possibly because those who formed the core ideological group within the PWA were Urdu writers and perhaps also because Urdu was the lingua franca in the years up till Independence. As a result, contemporary Urdu literature became the greatest beneficiary of this literary movement and within that, Urdu fiction blossomed as never before. In the years from the mid-1930s till the mid-1960s the genre of the novel and the short story in Urdu bore some spectacular fruit — a harvest so rich that it has still not been fully measured or appreciated.

A general misconception about the PWA is that all its members were rabid ‘leftists’ or members of the Communist Party of India (CPI) and that the PWM sprang fully-formed out of thin air in the mid-1930s. It certainly wasn’t so. While it is indeed true that a strong ideologically-driven group formed the nucleus of the PWA and served as an engine that determined the course and speed of the Movement, there were many writers who neither belonged to the CPI nor had a clear sense of Communist principles based on a thorough reading of its texts. Many writers professed a left-of-centre world view and given their propensity for a liberal, secular outlook could, at best, be called ‘fellow travelers’. The PWA was also not a foreign plant grafted onto Indian stock to produce strange and exotic fruit; it certainly was no hybrid offshoot of communist movements in Russia or the UK propagated in India by foreign-educated Indian intellectuals. The PWA was, instead, a heterogeneous group of writers – some established, others upcoming; some already committed communists, others with socialist leanings and a great many with no discernible ideological moorings save an inchoate desire to change the world.

***

Among the new crop of Urdu short story writers that came up in the years after 1936, Krishan Chandar (1914-1977) enjoyed the sort of fame that no other writer had known since Premchand. What is more, few Urdu writers can match his prolific output: 20 novels, 30 collections of short stories and countless radio plays! Together with Ismat Chughtai, Saadat Hasan Manto and Rajinder Singh Bedi, he is regarded as one of the four pillars of the modern Urdu short story. Krishan Chandar arrived on the scene with an altogether different temperament — different, that is, from the Premchand school of realism. His first collection of short stories, Tilism-e-Khayal (The Magic of Thinking), gives ample proof of a romantic temperament, a romanticism that no amount of association in the company of the more ideologically-driven progressives could ever truly stamp out and remained in many ways the bedrock of nearly all his writings. However, as the noted Urdu critic Khalilur Rehman Azmipointed out in a seminal study of the PWM, Krishan Chandar’s ‘romanticism does not flee from life, nor does it preach a yearning for death or an escape into a world of the imagination. On the contrary, his romanticism is another name for a passionate restlessness to change life. Krishan Chandar experienced the harsh realities of society in the midst of picturesque locales, lush fields and gurgling waterfalls. And that is why his stories have a nostalgic twinge and a sweet sadness, especially in the early stories such as Jhelum Mein Nao Par (On a Boat on the Jhelum) or Aangan (Courtyard).’

Krishan Chandar’s second collection of short stories, Nazarey (Scenes) shows a movement towards realism where an attempt towards understanding of reality can be seen gaining strength and the writer seems to catch the essence of those issues that lie at the crux of life without diluting the intensity of his feelings. ‘Be Rang-o-Boo’ (Insipid), Jannat aur Jahhannum (‘Heaven and Hell’), ‘Khooni Naach’ (‘Bloody Dance’), ‘Dil ka Chiragh’ (‘The Lamp of the Heart’) are some of the finest stories of this early period. From the point of view of literary aestheticism, ‘Do Furlang Lambi Sadak’ (‘The Two Furlong Long Road’) is one of the most memorable Urdu short stories. Like the stream of consciousness technique that was recently gaining popularity among Indian writers who were exposed to English writings, the story is free from the constraints of plot but the chain of thought connects to produce an intricately-woven sequence of emotions and experiences that lead us towards understanding certain fundamental truths. The stories in Nazarey portray how social realism began to take hold of Krishan Chandar’s writing but due to an intrinsically romantic temperament, he retained a deeply colourful, almost rhetorical tone even when he was writing socially-engaged, deeply-purposive literature.

To quote Azmi again, ‘There is such a variety of locales in Krishan Chandar’s ouvre and he tends to become so engrossed in portraying the natural surroundings of his characters that occasionally one feels that the writer is fleeing the ugly and complicated realities of life to run towards the innocent embrace of rural life. At such times, the colour of characterisation fades somewhat from his writings and like a poet, Krishan Chandar leaves us feeling that there is a mere external imprint of feelings.’ In an essay, Intizar Husain, another eminent Urdu critic and writer, has held this tendency to be a flaw and the writer Hansraj Rahbar too belies the greatness of Krishan Chandar as a writer. Rahbar believes that Krishan Chandar, having strayed from the values of socialist realism has sought refuge in imagination. But if one were to read his stories carefully one would find that Krishan Chandar is fully aware of reality and its many shades. If anything, he tries to talk about the ugliness of life that mars its beautiful surface; he resorts to vivid and colourful descriptions of nature and natural beauty to leaven his narrative which is often about the harsh realities of life. The lyrical descriptions of nature serve as a counterpoint to the unnaturalness that human beings have introduced into the natural order through their greed and meanness and cruelty. Empathy and understanding are the hallmark of his writing.

Born in Bharatpur, Rajasthan, where his father Dr Gauri Shankar worked as a doctor, Krishan Chandar enjoyed a certain cosmopolitan ease and bilingualism that few Urdu writers of his generation had enjoyed. After having spent the formative years of his childhood in Pooch, where his father served as physician to the Maharaja of Poonch, he moved to study at the Forman Christian College in Lahore to pursue a Masters in English followed by a degree in Law. As his wife, Salma Siddiqui says in an interview, Krishan Chandar’s mother was very keen that her son study law while he himself was inclined towards writing especially since the very first story he wrote, while still a student, was accepted for publication quite easily. What is more, the combination of acute poverty, sharp social inequalities and human exploitation that he had seen as a child in Kashmir had had a lasting impact on his psyche. Given his temperament, he could only have been a writer.

After a stint of writing radio plays for the All India Radio, first in Lahore then in Delhi and finally Lucknow, during the mid-1940s — where his colleagues were fellow writers Saadat Hasan Manto and Upendranath Ashk — Krishan Chandar moved first to Poona and then to work for films. His Lahore friends were already here — Chetan Anand, Dev Anand, Balraj Sahni. Bombay had emerged as the beating heart of the progressive movement; in fact a group of writers and artists, known as the ‘Bombay Progressives’ were busy crafting a new canon. Krishan Chandar took to this Bombay like a duck to water. In Poona, he wrote and produced two films, Man ki Jeet (‘The Victory of the Heart’) and Sarai ke Baahar (‘Outside the Inn’), and continued to take up writing assignments for films as and when such projects came his way. While not as successful as a film writer as his contemporaries, he was a quintessential writer. Writing as a craft, as an everyday exercise, as a means of earning a livelihood remained a life-long preoccupation. In fact, Krishan Chandar had penned the opening two lines of a story when he suffered a massive heart attack while sitting on his study table.

Influenced by Jonathan Swift, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, D. H. Lawrence, he wrote stories and short humorous pieces in both English and Urdu. This bilingualism and exposure to the best of western literature allowed him to make many introductions to the modern Urdu short story and the incorporated the technique of western story telling with such expertise that it appears to be his own. Added to his craft as a storyteller was a freshness and simplicity that was entirely new for the Urdu reader. ‘Toote Hue Tare’ (‘Broken Stars’), ‘Husn aur Haiwan’(‘Beauty and the Beast’), ‘Purab Des hai Dilli’ (‘Delhi is an Eastern Land’), ‘Shola-e-Bedard’ (‘Unfeeling Spark’) and three long stories of this period, namely ‘Zindagi ke Morh Par’ (‘On a Turn in Life’), ‘Garjan ki ek Sham’ (‘On a Night of Thunder’) and ‘Balcony’ are some of his most successful stories. According to Ihtesham Husain, the Marxist critic:

Among the new short story writers, no one has squeezed so much out of the descriptions of scenery and locales as Krishan Chandar has; nor has anyone tried to place nature in the context of human relations as he has. Kashmir, Gulmarg and Jhelum are not mere characters in a story; if anything Balcony, Nukkad (Corner) and Wadi (Valley) have a reality of their own.’

Another characteristic quality of Krishan Chandar’s writing is the tinge of sarcasm, or a rather rhetorical questioning, a quality typical of native speakers of Urdu who will state a thing in a manner when they actually wish to reinforce the exact opposite. Gradually, this sarcasm deepened and in the later stories, which can be regarded as his true masterpieces, the irony served to deepen the hues of realism and gradually became a literary tool that served the larger progressive cause. Stories such as Annadata (‘The Giver of Food’), Bhagat Ram, Mobi, Kaalu Bhangi and Brahmaputra are possibly his finest stories. All of them display all that is the best and brightest in Krishan Chandar’s craft as a story teller, especially Annadata which is one of the most biting critiques of the Great Bengal Famine with its astringent irony and its unsparing honesty making it one of the most memorable stories in Urdu.

***

Coming to Ghaddaar, while not the longest or the most well-known of Krishan Chandar’s novels, it is certainly the most compact yet moving piece of writing in his ouvre. Located in the span of a few days, possibly no more than a few weeks in the hot humid months of August-September of the year 1947, it is an account of an effete young man’s coming of age. A well-to-do Hindu businessman from Lahore, vacationing in his maternal grandparents’ home in the tiny village of Lala and carrying on a romance with a young Muslim woman studying in Lahore who is, like him, vacationing in her parental home in the village, despite being a much-married man himself and a father of two small children, Baijnath finds himself in the eye of the storm that has uprooted families and destroyed lives across the breadth of South Asia. The storm is called ‘Partition’.

Born to service-class parents with roots in feudal Punjab, Baijnath has known the best of both worlds: the scenic beauty and the serene secularism of the rural hinterland as well as the cosmopolitanism and liberalism of Lahore where he and his drinking buddies — Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and Christians too – make merry and live a life of ease and comfort far away from the rough and tumble of national politics. Hunted out from his maternal grandparents ancestral village by drum-beating, sword-wielding Muslims from the neighbouring village intent upon driving out all Hindus from their centuries-old homes, Baijnath tries to find his way to the sanctuary of the big city but there are no safe havens left for a Hindu in what has overnight become a Muslim city. Forced to leave forever the urbane Lahore of his carefree days, he tries to find refuge once again in his forefather’s landholdings in the heart of the Punjab but here too the once benign land has turned hostile.

Justly renowned for his lyrical descriptions of natural beauty, Krishan Chandar does not fail to delight his readers despite the grimness of the tale he must tell in Ghaddaar. As Baijnath is trudging along unknown country roads, he spots a wedge of swans, ‘their cheeks white as snow, their slender long necks arched,’ and is forced to compare their happy fate with his sorry one:

‘… these swans will descend on some distant lake and swim contentedly with their beloveds. If only they would take me with them where the boughs of the peach tree, heavy with blossoms, bends over the crystal clear waters to scatter its petals. And the five-coloured maahimaar and the rainbow-coloured tilhada scatter their colours.

‘Take me there, my friends; I shall play with your young ones. I shall lie on the green grass and watch the white plumes of the tall sarkanda bushes which will be waving like the white flags of peace in the clear skies. And I shall remember those dreams that Shadaan and I had once dreamt in the shade of the sarkanda bushes… Don’t leave me here, my friends! There is utter darkness in this world, and excessive cruelty and narrow- mindedness…

‘I can tolerate a little darkness. And surely there is some narrow-mindedness within me too. I too must have been cruel to someone some day. But I cannot tolerate such excessive cruelty, such darkness, such limitless meanness that one human being becomes thirsty for his fellow human being’s blood and is bent upon erasing every trace of his very existence. Put me on your wings and take me away, O swans! I haven’t slept for days. Sleep is roaming through every fibre of my body, but it cannot find a single spot to settle down upon. I will nestle among your soft as silk white feathers and fall asleep. I will lose myself in the kohl-dark coils of sleep and set off for the islands of my dreams.’

Baijnath is forced to face the uncomfortable truth while the swans can fly where ever they wish and settle down on any lake of their choosing, he as a mere human cannot. And that his land is no longer his; he must leave it forever in search of a new homeland or else be prepared to be chopped down like a radish or a carrot. The realisation comes after witnessing at first hand the murder and mayhem that has been let loose in the name of politics and the barbarism of those intent upon claiming the land as theirs at the exclusion of the ‘other’:

‘I felt as though all of Punjab was an old man – an old farmer with white hair whose beard had been set on fire by the communalists. He was burning in the fire of hatred and with him the honour and reputation of Punjab was also on fire. And that poor helpless old farmer was shedding copious tears from his eyes partly hidden in the folds of his wrinkled skin.’

And so Baijnath walks along country paths, ducking for cover when danger approaches in the safe haven of sugarcane fields, witnessing many a scene of blood and gore as he walks in search of the bridge over the river Ravi which will take him across the border to his new country. At one point, faced with certain death when he is surrounded by armed attackers, Baijnath blurts out: ‘What a strange fate I have! All my life I worked as a Communist and did propaganda for Pakistan. My entire life I worked for the freedom of the Muslims. And now that Pakistan has been formed, I find this staff is resting on my chest.’ And the narratorial voice carries on:

‘God alone knows how these words escaped from my lips. I don’t know which power made me utter these words! For, I was never a Communist nor had I ever taken part in any political movement. I was a well-to-do person happy living the good life. I had friends among Hindus, Sikhs and Christians and all of them were, like me, blithe and blasé. During the day we tended to our businesses in Lahore and in the evenings four or five of us would meet and make merry. What did we have to do with politics? Our interest in politics was limited to intellectual arguments, newspaper debates and bookish knowledge. Politics was for the hungry.’

Elsewhere, maddened by grief upon being told that his young son was killed by Muslims during an attack on their caravan as they crossed the border into India and that his unmarried sister was abducted, Baijnath gives in momentarily to the beast that lurks within all human beings:

‘All of my life I had regarded myself as a balanced, tolerant and completely non-communal sort of Hindu who had more Muslims than any others among his acquaintances. I saw myself as someone who had never been a part of communal violence, nor participated in the political or social movements that had poisoned the atmosphere of the Punjab for the past 50-odd years. I had always been extremely proud of my liberal mindedness and free thinking. But the moment I heard of my son being slaughtered and my sister abducted, my blood boiled and begun to bubble like lava; and I sat there cursing the Muslims and showering the filthiest abuses upon them. Where had that hatred come from? For a minute, I myself was amazed at the terrifying form and intensity of my own feelings. But the tide of revenge and anger swept all my ideals and lofty thoughts – like so many straws. Driven by rage and revenge, I got to my feet. Driven out of my mind with anger, I screamed, ‘Give me a knife, someone… give me a knife. Give me a dagger.’

Intent though he is upon finding revenge, he finds himself unable to do so in the most barbaric fashion possible — as other young men from his refugee camp are doing. They have managed to find a young Muslim women and Hindu men from far and wide are queuing up to take their turn in raping her. The hapless young woman is screaming for mercy as only a young woman from the Punjab can: ‘O brother, I am your sister.’ In the original, this is said in Punjabi thus reinforcing the essential oneness among the Hindus and Muslims of Punjab. Pushing his fingers in his ears, Baijnath finds himself unable to extract this most odious form of revenge:

‘But I ran away from that spot as fast as I could. As I ran, I slapped my face several times. Through my tears, I tried my hardest to convince myself to go back. I tried to conjure up Munna’s innocent face in my memory. In a bid to strengthen my resolve, I tried to take the help of my sister Suraj’s guileless face. But each time Suraj’s face would dissolve and transform into the face of that Muslim girl. In the desolate wilderness of my soul, the sound of the primordial woman began to echo; it was screaming and calling out to the man within me…

‘O brother, O bother of mine…I am your sister!’

But fate has more trials in store for Baijnath. Ballo, a famous wrestler from Lahore and a self-appointed strongman among the Hindus refugees, decde that they must wreak havoc upon a group of Muslims waiting to cross the bridge across the Ravi. what better way than this to extract vengeance for the losses the Hindus have suffered as they have travelled across the border? When Baijnath, who wants no part in this organised slaughter, asks why this should concern him Ballo, speaking for the monster that takes the guise of a mob, taunts him:

‘Yes, yes, indeed, why should it concern you?’ Ballo’s tone hardened. ‘Pakistan has been created precisely by such cowardly Hindus. Even when their own father dies, they still say: How does it concern me?’

And so taunted and bullied and prodded into being part of a murderous mob that attacks a group of Muslim muhajirin waiting to cross the bridge across the Ravi, Baijnath witnesses by far the goriest scene he has in the course of his ardous walk from the serene village of Lala to this field of Dakki beside the Ravi on this side of the border, a journey that is as much a rite of passage as a flight to safety. Baijnath finds himself riding a horse, a spear in hand, in the thick of a carnage. Loud cries of ‘Allah ho Akbar’ mingle with equally loud cries of ‘Har Har Mahadev’ and ‘Sat Sri Akal’. Swept away in the rush of the moment quite beyond his control, Baijnath finds himself chasing a terrified Muslim in a torn vest and grimy tehmad running to save his life and that of the small boy he’s holding in his terrified arms. But just as Baijnath’s spear is resting on the old Muslim’s chest, everything around him becomes crystal clear: ‘That picture of that single moment still swims before my eyes. The old man’s mouth was agape with terror, his slightly raised hand was trembling with fear and entreaty, and his chest was visible through his tattered vest. The point on which my spear rested on his chest, I could see some white hairs – the white hairs were exactly like the ones on my father’s chest. The old man’s eyebrows were white too, just as my father’s were. And the softness and entreaty with which he said ‘No, no, son, don’t kill me’, the tone of his voice reminded me of my father.’

And, suddenly, as tears begin to prick Baijnath’s eyes and he was about to remove his spear from the Muslim’s chest a stern voice came from behind him, ‘Oye, you Brahman dog! You can’t fight, can you? Get away! You traitor!’ The word ‘traitor’ here is a gaali, a term of abuse.

With these hurtful words, Ballo comes riding swiftly on his black horse and, piercing the old man’s chest with his spear, moves on. In the blink of an eye, Baijnath sees the old man totter and fall behind the flying hooves of the black horse and the small child he had been holding, tumbles and rolls away into a ditch. ‘And then scores upon scores of feet trampled the ground and moved on. And I could see no more as my eyes were filled with tears. As I sat on the horse, my entire body trembled. A wave of nauseous remorse swept over me consuming my mind, body and soul. With a sudden movement of my hand, I flung the spear far away. Turning my horse I rode away from that butcher-house.’

Later, Baijnath hears that military assistance reached that spot beside the Ravi after four or five hours. But by then the attackers had finished their business and run away and thousands of Muslims had been slaughtered in the famous field of Dakki. But the ‘traitor’ Baijnath — who, at the crucial moment, found himself unable to kill an old man, an old man whose white hair reminds him of his father’s white hair — finds redemption. In the murderous field of Dakki, he finds something rare and precious that is way beyond revenge. The self-seeking, luxury-loving, self-proclaimed apolitical Baijnath emerges as a man of fine mettle. Despite his many frailties he has nevertheless come through the fire of hatred and revenge relatively unscathed. Despite the gravest of provocation, he has managed to keep the human inside him from turning into a beast.

I will conclude with the question I asked at the beginning of this Introduction: Who or what is a traitor? The answer is given by Baijnath when he overcomes the black tide of anger and hatred and instead chooses to find the human within himself:

‘I asked myself, ‘Why do we walk with our head held high? Why do we assert the superiority of our civilization? Why do we shy away from acknowledging our sins? These unformed, immature civilizations hide so many unfathomable darknesses within them. All this talk of Hindu civilization, Muslim civilization, Christian civilization, Sikh civilization, European civilization, Asian civilization! So much horrifying darkness, so many bottomless depths are hidden in them! But no one ever talks about them. They only talk of their beauty and grandeur and majesty. If one finds the courage to push away the beautiful outer raiments to look deep inside, he is considered a traitor.’

Not a conventional hero to begin with, Krishan Chandar’s Baijnath nevertheless emerges as a man with sterling qualities. Braver than the brave-hearts who fight battles and win wars, he has slain the demons inside him and gained victory over every baser instinct that man is prey to. He is not a traitor; he is a stalwart, a loyalist loyal to goodness and humanness.