While the world mourns the end of an era with Appaji leaving her mortal torso, I’m reminded of her frequent allusions to the Ganges — ‘Ganga ji’, as she would call her — as a metaphor for life, meandering through myriads of lands, and merging into the ocean only to re-emerge in a game of unbroken eternity. Her eyes used to glisten as she recalled her swimming expeditions in the river. It was on the sandbanks of this perennial life force, that she touched the raging fire of ‘tadap’ (‘yearning’ is the nearest translation) for the first time. She internalised the struggle of a shrivelled fish, trapped on a parched patch of land, yearning to swim back into the river.

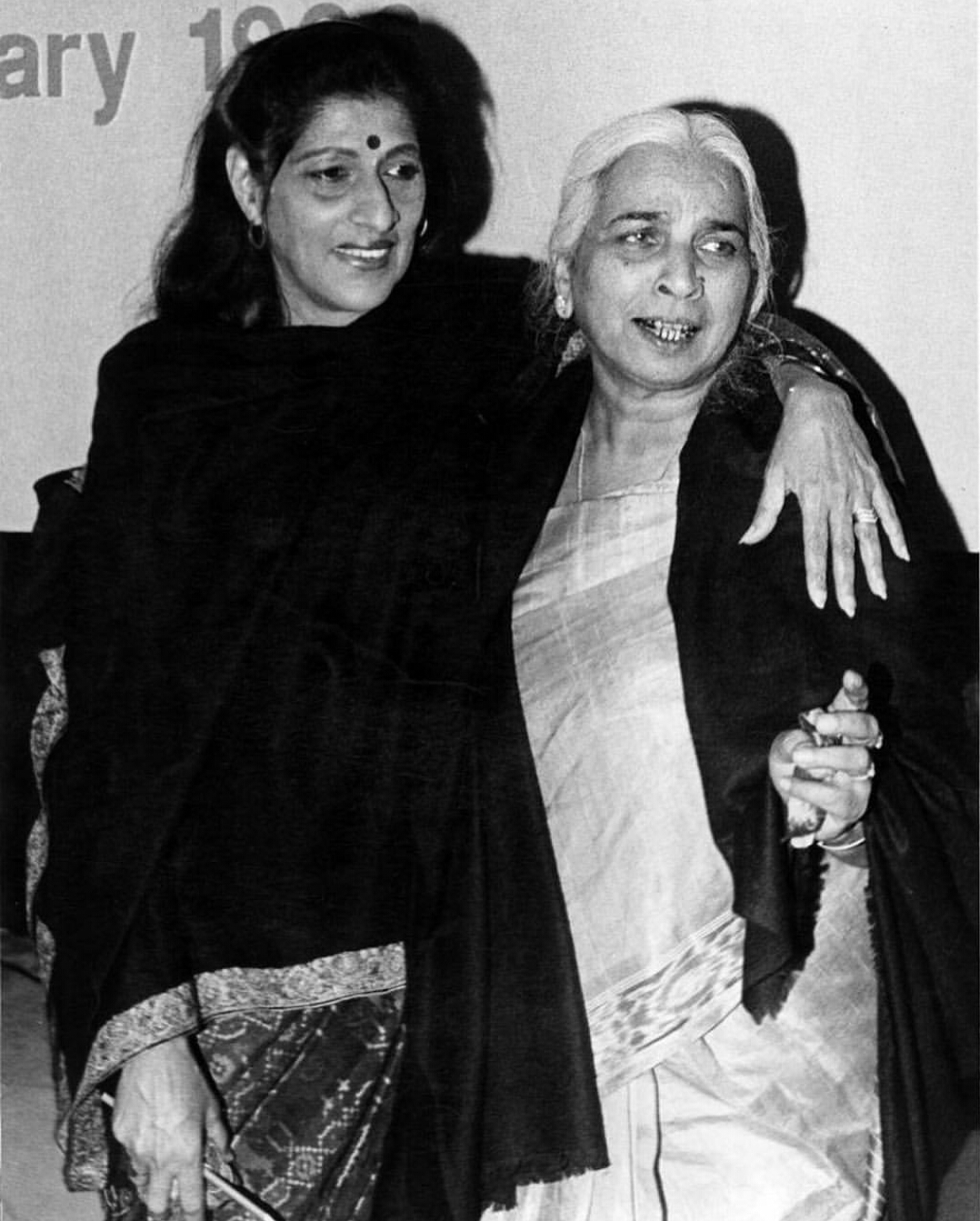

Having no training in music, I was the most undeserving of her students and yet she consciously took me under her wings, much to the bewilderment of her senior students. She would switch from Gaud Sarang to Malkauns and Yaman, in order to ensure that I didn’t feel alienated or left out. The grand old lady whose complex tappas flashed brighter than her diamond nose-stud, who spent mornings teaching ragas like Desi Todi and Surdasi Malhar, would make me learn paltas in Bilwalal, in the evening. Her patience knew no bounds and her presence soon became a sanctuary of sorts. Staying at Appaji’s was a holistic experience. From savouring her favourite Banarasi delicacies (worth mentioning are chura-matar, Banarasi pulao, and kele ka kofta), to watching reality shows on television, Appaji brimmed with life. My fondest memories are those of the slightly longish summer afternoons, when we would listen to the Banaras old masters like Siddheshwari Devi and Mahadev Mishra after lunch, as the sun languished outside the curtained windows of her room. I would incessantly ask about her Banaras days, and she would paint the everyday and the spectacular before me, now the sun sneaking in through a crevice to touch our conversation, driven by an irresistible urge to merge with the waters in Banaras, where Appa heard the darling songstresses of yesteryears in barges afloat on the Ganges. I wonder if they still put up swings during the rains, if the barges still resonate with piloo chaitis on Budhwa Mangal (the first Wednesday after Holi), if they get roses from Mirzapur to celebrate Gulabbari (a festival to mark the arrival of spring). I wonder if anyone ‘lives’ Banaras as our Appaji did. Did she not, after all, live like she was Banaras’ own fish, who knew its streets, like fishes know water? Otherwise, how could her enunciation of phrases like ‘jale ko aur jalana’ (to scorch the burnt) in the fabled dadra deewana kiye shyam and ‘tadapu jaise jal bina machhaliya’ (I yearn like a fish out of water) in her self-composed dadra in Mishra Kirwani, leave listeners so unsettled?

This fire moulded the phoenix that inhabits two of her nayikas, virahotkanthita (agonised by separation) and vipralabdha (deceived by her lover) – their anguish reducing them to ashes, their unflinching hope making them more alive than ever. Appaji embodies this cyclic continuity, and she was born into it. Her baramasas were rooted in the agrarian cycle of Eastern Uttar Pradesh, in its matrilineal quilt of succeeding seasons, which smelt of the early summer sweat and the monsoon petrichor. She embroidered this delicate heirloom of hers with utmost dexterity, like a craftsman, dying it in the rich, court-born hues of the Seniya and Banaras traditions, and yet retaining the lilting simplicity of purab.

I can visualise Appaji in one of her suave Banarasis, in pink, mauve, fawn or mint, its zari carrying a foliage of persianate creepers, inundated by her love for traditional textiles. Appa herself is part of the kinkhab, weaving her own brocade in the choicest of silver and gold threads. She sings a tap-khyal in Bahar — ‘gulshan mein bulbul chahake, dekho bagh bahar’ (the bulbul chirps in the garden, look how spring arrives in the garden), you see a bulbul fleeting from one branch to another, flying past sagging clusters of madhumalti. Appaji imagines a field of nargis flowers, called the poet’s narcissus, while the intoxicating fragrance of her paan wafts through the air. Her unique pedagogy made use of Amir Khusrau’s riddles to teach me the ‘art’ of washing and storing her treasured paan ka patta, which travelled all the way from Banaras to Calcutta. I knew I was inching closer to Banaras, to the resonant courtyards of kabir chaura, to the peeling murals of its temples, to its ‘ka guru, kaisan ho?’masti. Appaji became the microcosm of Banaras for me, laying bare the increasingly complex cultural narrative of the city, not just as an estuary of confluence, but also as a field of contestation for the classical Sanskritic, courtly Persianate, and agrarian folk traditions. The quintessentially Mughal foliate arches and Shahjahani balustrades of the Ramnagar fort-palace provide the backdrop for the spectacular theatrics of Tulsidas’s Ramayana every autumn, attended largely by farmers from neighbouring villages. Appaji, with her colossal repertoire of forms like dhrupad-dhamar, chhand, prabandh, dharu, matha, trivat, chaturang on one hand, and khyal, tappa, tap-khyal, gul, naqsh, qaul, qalbana, rubai and tap-rubai on the other, quite seamlessly became a practitioner of the ganga-jamuni culture. She had, to a great extent, internalised the cardinal precepts of medieval devotionalism. The ‘act’ of beholding the object of love, the Bhakti practice of darshan, often emerged as the ‘destination’ of her songs.

Appaji’s interpretation of texts was historically informed, yet rooted in her present. Her renditions were intimately personal, yet universal. While rendering thumris, she would always take the ‘lover’ as a variable, assigning different personalities and roles at different points in time, thus keeping the text fluid, yet confined within the realm of her aesthetics. As musicologist Peter Manuel said, a good thumri text is ‘incomplete’ in the way that it allows the vocalist to emotionally explore it subjectively. Appaji went on to weave moods, inlaid with emotions. The lover whose presence and fidelity is craved for remains rather passive, while the beloved emerges as the protagonist of the tale. She restlessly rests on the delicate thread of Appa’s poetic translations — abstractions to images, memories to re-enactments, scintillations to sounds. By the time the thumri reaches its laggi, the fast-paced concluding segment, Appa herself becomes the protagonist of the song. Her passionate readings of both classical and contemporary literature helped her develop a new semiotics of music. Her use of aaroh (ascending notes) to illustrate the lover’s departure, and avroh (descending notes) to signal his arrival, gives mobility to the text. While singing the poignant Banarasi dadra ‘chala re pardesia’ she travels from Bhairavi to Todi to Sohini and glides back to Bhairavi again in saying ‘savere chale jaiho naina milake’. Appaji could effortlessly evoke the anxieties of separation, especially the anticipation of a nearing separation, looming like a dark cloud. She could bring to life the frothing turbulence within with utmost calm.

Now, as I write this, I yearn for that piece of Dairy Milk which came with the sweetest call ever, “le, aadha tu kha, aadha hum khayenge,” to be followed by an equally endearing “aur le le.” I would love to believe that Appaji’s on a concert tour, travelling with her creaseless, starched sarees, Gods, and bandishes, only to come back in a month or two. For we are not prepared to experience the tadap of separation that plagues her nayikas.