Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

…

What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden. My words echo

Thus, in your mind.

(T S Eliot, “Burnt Norton”, Four Quartets)

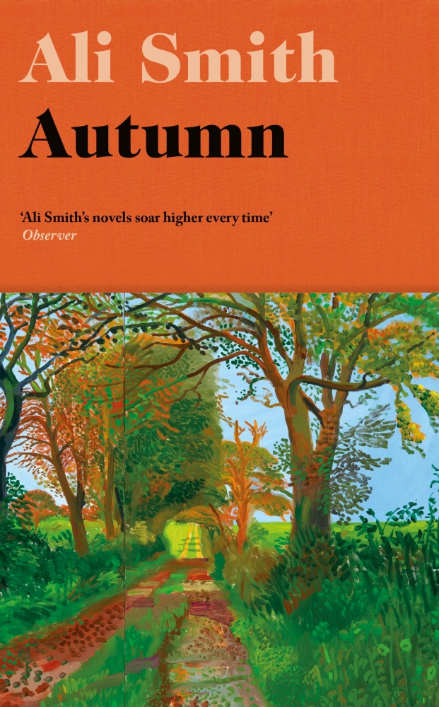

We live in times where the world we thought we knew has turned upside-down. We can perhaps make sense of this distortion through our understanding of time. We live in what is now called a “post-truth” world. But where can we locate truth in time? And where is the exact turning point in time that becomes “post” truth. In other words, does truth cease to exist after a certain point in time, and where can we locate that point? How do we experience time? The times we live in, our “historical present”, is often labeled as post-something: we also live in a “post-Brexit” world, which suggests a more obvious placement in time. What kind of a world is a “post-Brexit” world? Is it a new world? Is it any different from a world that was “pre” Brexit? What implication does a post-Brexit have for us? Are we also situated in a similar post-acche din world? Ali Smith explores what it means to live in post-Brexit UK in her novel Autumn — a novel shortlisted for the Booker Prize this year, and the first in a series of four novels based on seasons –through time and our various notions and experience of it. Autumn is also the first post-Brexit novel.

Autumn is a dialogue on the nature of time; how it can help bring an understanding of the world around us, and the times we live in. “[T]he novel as a form is always about time”, Smith said in an interview. She plays with the structure of the novel through the fluid narrative and the various layers of time embedded in it. The novel has an overarching time and place, which is post-Brexit UK. This post-Brexit moment coincides with the cyclical and linear movement of seasons. Human beings experience time in complex ways, and Smith beautifully elucidates this in the aforementioned interview:

The way we live, in time, is made to appear linear by the chronologies that get applied to our lives by ourselves and others, starting at birth, ending at death, with a middle where we’re meant to comply with some or other of life’s usual expectations, in other words the year to year day to day minute to minute moment to moment fact of time passing. But we’re time-containers, we hold all our diachrony, our pasts and our futures (and also the pasts and futures of all the people who made us and who in turn we’ll help to make) in every one of our consecutive moments / minutes / days / years, and I wonder if our real energy, our real history, is cyclic in continuance and at core, rather than consecutive.

The novel depicts a beautiful relationship between a 101 year old man, Daniel Gluck, and a 32 year old woman called Elizabeth – a relationship that is “life-long”, and was perceived to be the moment they met one another, when Elisabeth was only a child, and Gluck her quirky neighbor at the time. The narrative flits from memories, to the present, to the world of dreams, which makes up this complex experience of what the philosopher Paul Ricoeur calls ‘phenomenological time’. This is central to the sensitive portrayal of this special relationship. The past and futures of the characters, as Smith says, make one another; the very being of Elizabeth, and the way she sees the world, even in her adulthood, is made up of her memories with her neighbor and all that she learns from him. And it is time and the narrative of the novel that also helps us, along with Elisabeth, see the world in a new slant.

The season of autumn is a metaphor for this post-Brexit moment. It represents a time of change, transition and transformation. It is a time where fences and borders are built in neighborhoods; a time where “GO HOME” is scrawled on building walls; and where systems are placed with rigid bureaucracy, only to mark and spell out boundaries — walls built both in the mind, as well as the world outside. It is a time when nothing really makes any sense. David Gluck’s lyrics to a song he wrote says:

Snow is falling in the summer/ Leaves are falling in the spring/ Gone the reasons, gone the seasons/ Time has gone and taken everything

Summer brother autumn sister/ Keeping time through time/ Autumn mellow autumn yellow/ Give me back a reason to rhyme

This song is imbued with Keatsian melancholy, but it is less hopeful; there is no reason to live, time itself is suspended and askew. And rightly so. Gluck was estranged from his sister in war-time Nazi Germany. (This song also brings to mind Auden’s “Funeral Blues”.) But the season of autumn also suggests that there is the potentiality and inevitability for change; there is the possibility for a different world, a world post, post-Brexit. And this is the very nature of seasons and time in its cyclicality. There is the possibility of ‘mellow fruitfulness’, harvest and ‘ripeness’ (Keats, ‘To Autumn’). There is also a Keatsian melancholy in envisaging this fruitful world – also, what does ‘harvest’ mean? What kind of a world are we envisaging? The novel provides glimpses of these in its richness and subtlety, in its ‘mist and mellow fruitfulness’.

The season of autumn also contains traces of that which was – the abundance of spring and summer (“It doesn’t feel that far from summer, not really.”) In Time and Narrative, Ricoeur says that the past and memories have a “strange power”: they are “past things…which ‘still’ exist”. This is also a cause for hope; the past, because it ‘still’ exists in the present, cannot be so easily eroded in the menacing future of a post-Brexit world.

The intersection of the past, present and future — where past and future is located in the transient present — is what Ricoeur calls the “distention” of time. This distention, which is a hopeful phenomenon in the context of the novel, is expressed in various ways through the fluid narrative structure of dreams, memories, and pasts, both remembered and forgotten. It is also where phenomenological time experienced by the characters interacts and negotiates with the historical moment of the novel. It is in this negotiation that the characters, as well as the readers, perhaps find answers, or ways to cope with the burden of history and time. “Distention” is the very human experience of time and is lived in the mind. In one of the many flashbacks in the novel, David Gluck says to Elisabeth: “Time travel is real… We do it all the time. Moment to moment, minute to minute.”

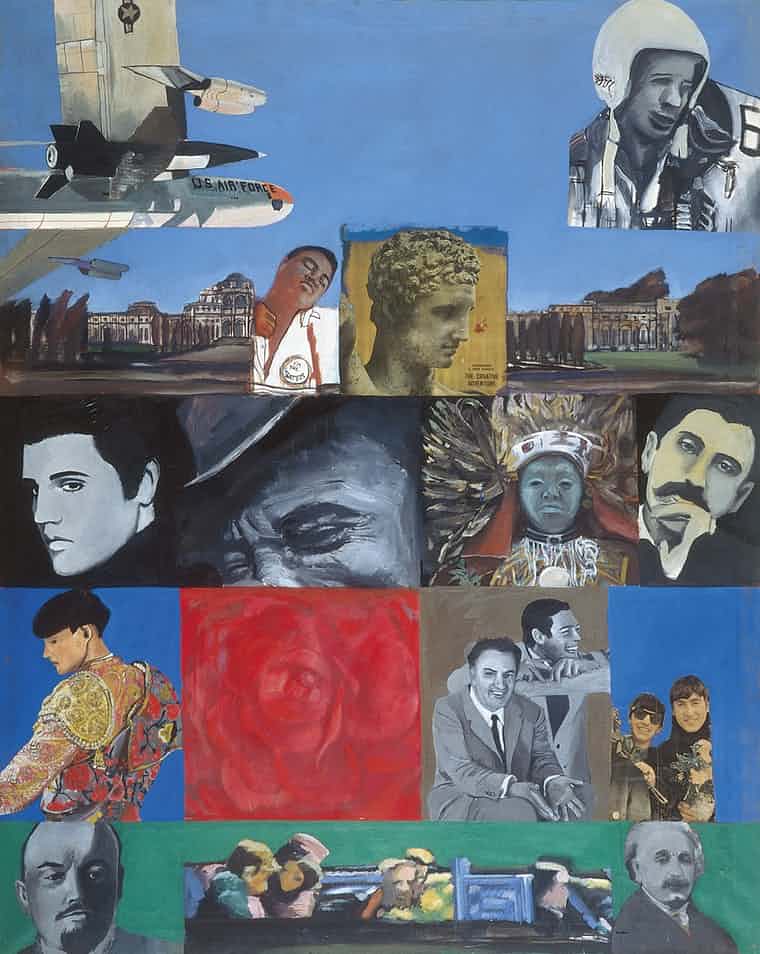

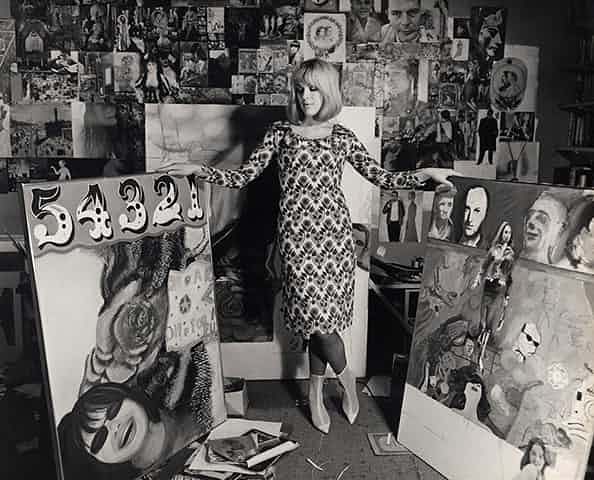

In one of the fragments of memory in the novel, Gluck says to Elisabeth when she was a child: “It’s alright to forget… I imagine that whatever it is I have forgotten is folded close to me, like a sleeping bird.” The past is never really fully forgotten; it is still alive and takes the form of a “wild bird”. The novel sheds glimpses on the life and art of the forgotten “wild bird” that was the underrated British pop-artist Pauline Boty. Her story, and the descriptions of her vivacious and intriguing art, is interspersed through out the novel through the flashbacks of conversations between Gluck and Elisabeth. Soon after her tragic and early death, Boty was forgotten in art history. This had very much to do with the fact that she was a woman. Her due place in history is being restored only now. (Some of her art is still missing). Gluck conjures up the vitality of her art, and what she represented – a woman much ahead of her times – through his memories of her art. In this manner, Pauline Boty is brought to life. In bringing Boty to life, Gluck is also bringing back to life the “high confidence” that she epitomised. She had the talent of making a positive, artistic explosion from the negativity and tragedy in her life. This high confidence is not only reminiscent of the vitality of Boty and the past she embodies, but also calls for empowering possibilities and alternatives for the future. It is especially poignant that Boty is resurrected at a time that is in need of this high confidence, energy, wisdom, and talent, in order to confront the future and the world that is at hand. There is the “nostalgia of NOW”, which anticipates a future with its myriad possibilities, while bringing to life a forgotten past. This resurrection of a vital part of history also suggests that the wild bird of the past does not disappear; and even if it does, it finds its way back to the present.

The interplay of time in the narrative of the novel holds much meaning for a world that is in transition. Time and history is cyclical, and there is nothing that can stop this wheel of time. The world is in a process of becoming, but it need not be the future that is now. Perhaps this historic moment is a moment that has arrived and yet not arrived. This is beautifully depicted through the season of autumn. The fluid narrative structure and time frames defy the present moment and a fixed future with divisive walls. There is some solace in that. Ali Smith could have well won the Booker for this beautiful, inventive, and intriguing work of fiction.