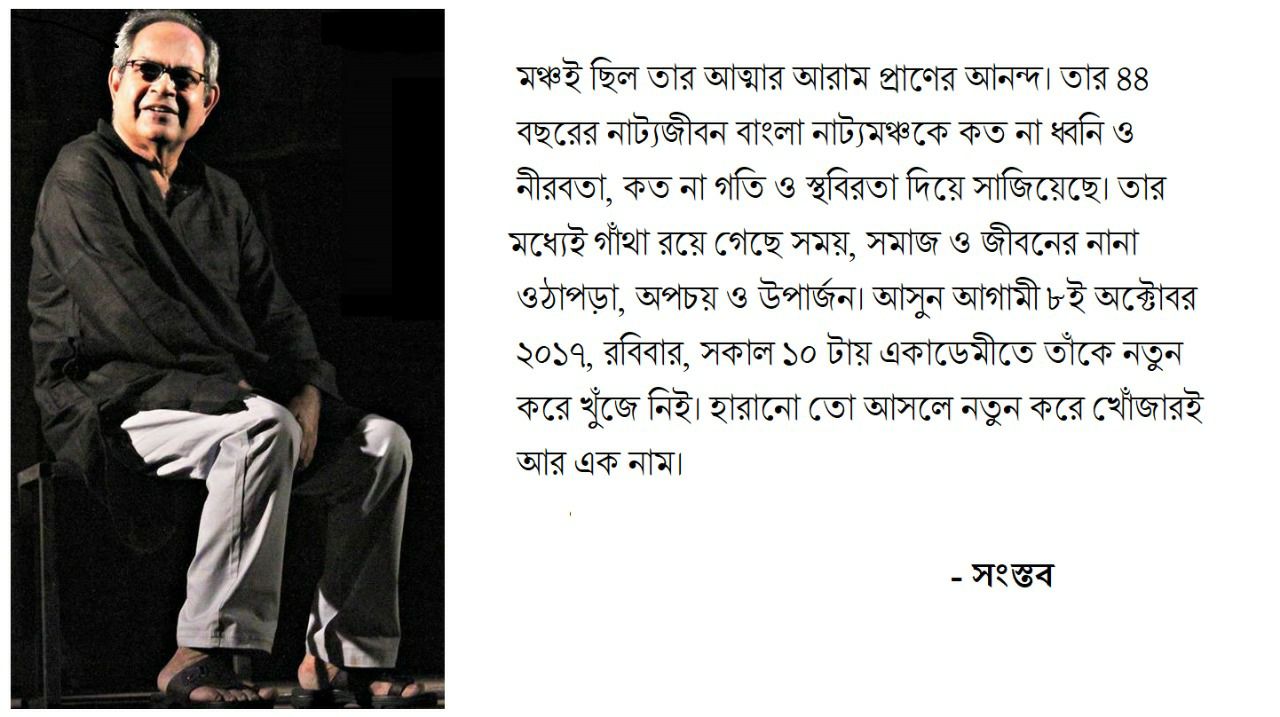

While several obituaries have flown in after Tom Alter died on 29 September, 2017, the death of another veteran actor and director, whose work, too, has primarily been in theatre, received little attention. Dwijen Bandyopadhyay, director of the theatre group Samstab, passed away amidst Pujo festivities on 27 September 2017. He was 68. A known figure in the Bengali film and television industry, Bandyopadhyay is most likely to be remembered for his four-decade-long work in Bengali theatre. While his death did receive attention in the Bengali media, it was hardly reported by the national media. A comparison with Alter’s reception in the national media shows the disparity in the coverage of “regional” news and national (read Hindi/ Urdu) news. This is not to take away from Alter’s work: he deserves as much adulation and probably more, but the relative silence over Bandyopadhyay’s death shows the vast difference between the power play of different languages in India, and its effect on the various “regional” theatres. (The 2017-18 prospectus of the National School of Drama makes it clear that plays will mostly be performed in Hindi.)

Bandyopadhyay was a much loved and much revered figure as an actor. He had admirers across political lines: both Mamata Banerjee, the Chief Minister of West Bengal as well as Surya Mishra of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), grieved his death. Bandyopadhyay, however, was a Left-leaning intellectual.

Saddened at the passing away of veteran actor DwijenBandyopadhyay. Condolences to his colleagues and family

— MamataBanerjee (@MamataOfficial) September 27, 2017

Thespian DwijenBandyopadhyay will be remembered by generations. My sincerest condolence.pic.twitter.com/dNroXtY6Z1

— SurjyaKantaMishra (@mishra_surjya) September 27, 2017

Bengali buddhijibis (intellectuals) have always had a close relationship with power. Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, the former Chief Minister had also written a play when he was the Minister for Culture, and Bratya Basu, a playwright and director, is currently a Minister for Tourism for the Trinamool Congress government led by Mamata Banerjee. When a large number of intellectuals came together to speak against the violence committed by the then-Left Front government in Nandigram in 2009, Bandyopadhyay chose not to go public against the ruling Left Front. With his demise, the cultural Left in Bengal sees another loyal member passing away. I write this because his affinity with the socialist imagination had a symbiotic relationship with his vision for theatre.

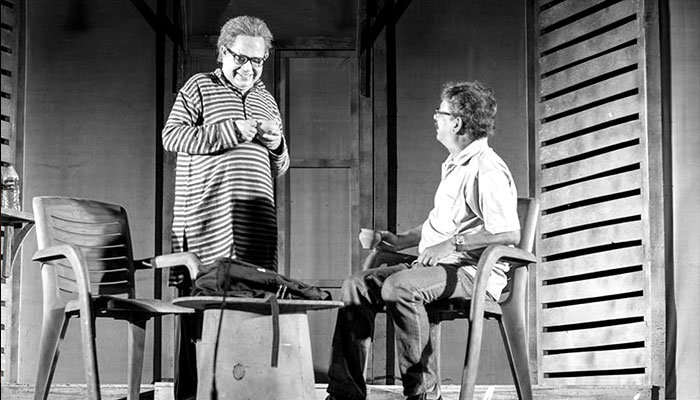

Bandyopadhyay rose to prominence in the 1980s, for his acting in the play Amitakkhor, which was performed by the theatre group Sudhrak. He worked alongside the finest actors that Bengali theatre has seen, from Shambhu Mitra in the initial days, to Soumitra Chattopadhyay in the years leading to his demise. When he left Sudhrak, however, he did not do any theatre for some time. Then, he formed Samstab. He directed plays for this group until his last day. There is a wide consensus that he is the best actor in the generation that rose to prominence after Ajitesh Bandopadhyay, Bibhash Chakraborty, and Arun Mukherjee. In 2014, I met him after he performed at the Bharat Rang Mahotsav. For a brief while, we spoke about his contemporary, Ramaprasad Banik, who passed away in 2010. Banik, also an actor and director, was widely considered the best director of this generation of thespians in Bengali theatre. With Bandyopadhyay’s passing, it can be said that the same generation has also lost their most accomplished actor.

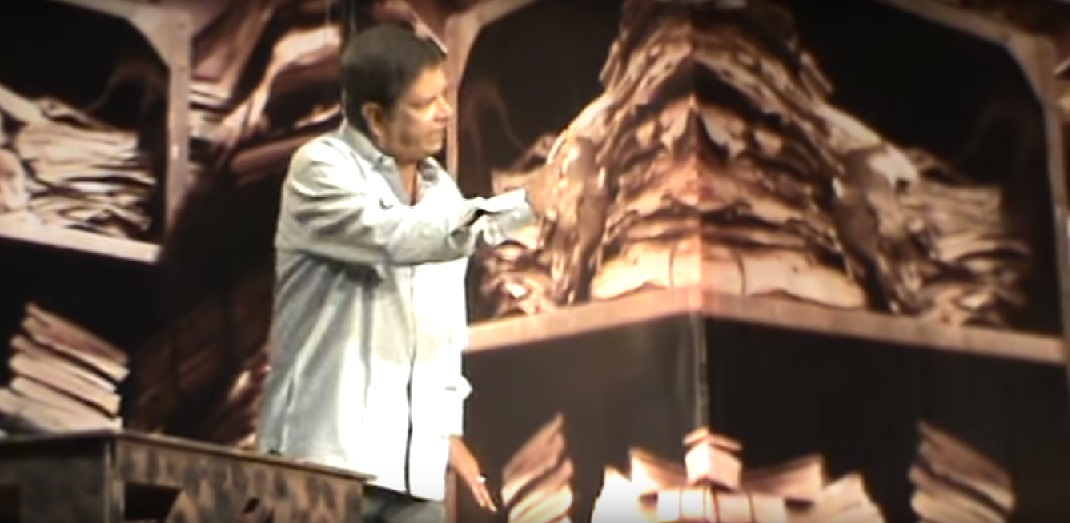

The two, however, differed in their approach to theatre. “Our vision of the theatre was different”, he said to me during an interview in 2015. “While I tried to break every convention that the theatre had, Rama stood by them, and showed all of us how relevant convention is.” In Bengali theatre, there has been a lack of imagination beyond plays that take place in drawing rooms. Bandyopadhyay, however, often showed that drawing rooms have the possibility of being something else. It is not a coincidence that Bandyopadhyay worked closely with Mohit Chattopadhyay, who experimented with plays right from his first play, Kanthanalite Surjo (A Sun Stuck in My Larynx). Rooms often transformed into other symbolic forms in the plays Bandyopadhyay directed. This picture from Bhutnath below shows an office, but the design of the set is not realistic at all. Images of the files are much larger than they usually are.

Bhutnath is a character who types in the air, and cannot stop. He is one who has reconciled his human life to mechanical life. The set, therefore, could also stand for the Bhutnath’s mind. On the other hand, Banik, also a playwright, hardly moved away from naturalism. That Banik and Bandyopadhyay, who have two different approaches to theatre, worked alongside each other, shows the range Bengali theatre had since the 1980s.

In an article titled “Obinoyer Ami” (In Acting, I Dwell), Bandyopadhyay says, “An actor does not merely tell the story of a character; he/ she reminds the audience of his/ her context. I have never forgotten this mantra. I have tried to avoid gimmicks, and yet, at the same time, build a character, make him/ her a person whom the audience can easily love”. Indeed, in a theatre that is largely known for a boisterous form of acting, Bandyopadhyay always seemed to act less, often not act at all. Subhankar Ray, in his tribute to the actor, records his impression of Bandyopadhyay’s acting in the play Spordhabarno:

After the curtain raises, and the play Spordhabarno begins, a man enters the stage. In his hands, equipments for gardening. His walk shows that he has tired feet, but, from his look, we understand that he is irritated with something. It’s because he is waiting for someone. He keeps all the material for gardening in their right place on the stage, very carefully. In between, he keeps glancing at the front door impatiently. After some time, he is walking towards the writing table as if he has lost all hope; his eyes can’t take any more pressure. He pulls out a pen and a paper; begins writing. Even then, he doesn’t seem to be at peace. Some moments pass by in this way. We gradually see him becoming too engrossed in his writing; his entire weight is on the pen. After he has progressed with his writing, a person comes and stands in front of the door. Upon hearing this person’s voice, he looks up. He walks towards the stranger with rapid steps, welcomes him. We realise this was the man he was waiting for all along. This entire sequence takes four to six minutes of stage time. There was not one dialogue.

The play was written by Chandan Sen and was inspired by Václav Havel’s plays. Subrata Ghosh, in his review of the play published in Desh, said that the play was important for its formal experimentation in form even though it is a political, anti-Fascist play. A commitment to politics is one of Bandyopadhyay’s core concerns, but, as I have said before, he often experimented formally at the same time. He explains how his politics affected his plays in his interview with Kahoon:

There are a few vices in our society that is segregated by class. Inspite of our aspirations, our dreams to build a socialist structure in independent India, capitalists control our lives. In such a scenario, we will have to become a kind of man who lets go of those vices. We will not let them enter our consciousness. We will try and live in a different way. When a group of such people gathers together to form a kind of collective, with one common aim of doing theatre, we start our journey. You can call this group a collective, a sangha, whatever, but they must believe in a common philosophy… The situation now is such that it is difficult to find people who share a common worldview. Even I can be held guilty for this. People don’t even seem to think so much nowadays. We thought we would control our lives, our environment, but, instead, we are the ones who are being controlled. I’m given a set of rules, and I am told I have to follow them; and I’m starting to do my theatre within this structure. There is only one way to change this: control, instead of being controlled… We are living at a time when the middle class has prospered a lot. They’re becoming consumers in a culture that encourages consumerism. As a result, theatre too is becoming a place for consumption. I’m not saying that theatre is a place for sadhus and saints. But theatre has an aim; we are moving away from it.

Indeed, many of Mohit Chattopadhyay’s plays that he had directed had middle-class protagonists who try to fight their surroundings. In Mustijog, Samstab’s most successful play, for instance, Bandyopadhyay played a character that suddenly begins to punch others. When a psychiatrist comes he says that there is another person who is repressed within the character, and that person is a fighter who has begun to show his presence. Bandyopadhyay’s character is then shown to punch goons, drunks, in the course of the play. At the end, he tells his boss in the office, “Every person comes to this world to create a miracle. Even an ordinary person like me can create a miracle.”

Both Bandyopadhyay’s vision for the theatre and the socialist imagination imagines man to be in control of his self; man who can control his own life; man who is extraordinary, beautiful; man who is a creator. To rephrase Rousseau’s famous saying, Bandyopadhyay’s theatre believed that man is born in chains, but he looks for freedom everywhere. In his death, we hope that he finds the freedom he longed for in life.