Karnataka is the second state to think of passing a law to curb some of the most dangerous and anti-human practices related to irrational beliefs. Having worked in the field to eradicate superstitions over the past four decades in Karnataka, it is time for me to put down a few opinions on this proposed law. The Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations, of which I am the president, has been demanding a law to separate religion from politics, a common civil code, and laws to protect the people from the machinations of those who claim to possess, or control, supernatural powers.

The demand for such an Act at the state level was first put forward by the Maharashtra Andha Sharddha Nirmulan Samithi (MANS), and Dr Narendra Dhabolkar worked for a long time to get it passed in the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly. But it got blocked in the legislative council by those with vested interests. For several years, MANS worked hard to make amendments that would make it acceptable to all. But despite these compromises, the Act was still not passed. Whenever I met Dhabolkar, I would ask him about it and the reply would be that more compromises were required. We have every reason to believe that it was this attempt to push the Act that resulted in Dabholkar’s assassination. After he was sacrificed, the Bill was passed. This was very much a watered down and weak version of what Dabholkar intended; but it was accepted because something would be better than no such law at all.

Following the protests against Dabholkar’s murder, we had proposed that such legislation should be enacted for Karnataka too, as our problems were similar. The legislation would be a step to eradicate superstitions from a deeply religious society like ours, where exploitation of the gullible is age-old. The work involved went on; we found that even the then Chief Minister of Karnataka, Yeddyyurappa, was not free from superstition.

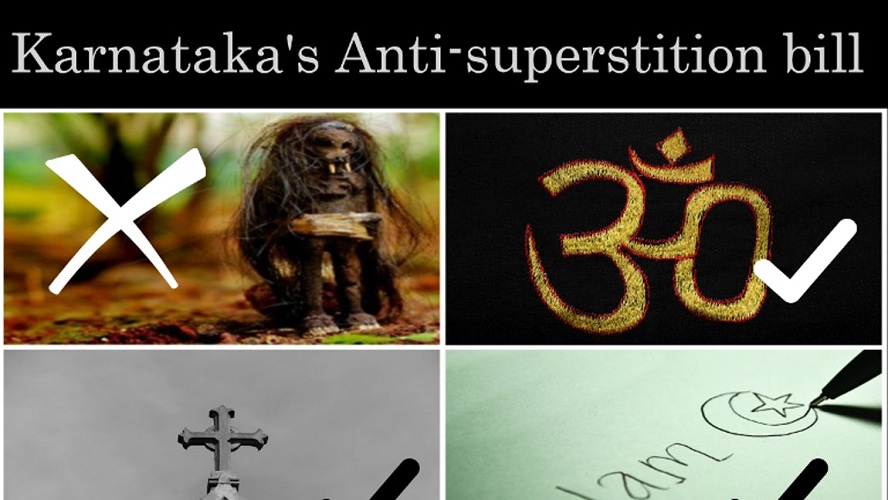

Our efforts were supported by a good number of progressive thinkers, organisations and even some of the progressive mutts. Though it seemed strange that religious institutions would support such legislation, some of them did, and they even took the initiative to bring together the various supporters. This was followed by two draft bills: one by the National School of Law at Bengaluru and another by the State Law University at Dharwad. These were consolidated and put forward for public discussion. An attempt was made to address a number of superstitions such as astrology, vaastu and palmistry. At the same time, a few issues such as made snana (rolling over the leaves on which brahmins have eaten), pankti bheda (caste-based places for serving meals) were brought in. This was followed by great opposition from the Hindutva groups. They claimed this was an anti-Hindu law; they tried to scare people by saying that a tilak or a bindi would be considered punishable under the law, and so would a tulsi plant! The Lok Sabha elections were due at the time; the government developed cold feet; and the bill was put in cold storage.

Later on, when M M Kalburgi was assassinated, the agitation for the legislation began again, this time with the demand that the Act be named after him. A number of meetings were held, including one at Freedom Park at Bengaluru which was attended by two ministers of the Karnataka government. I remember questioning them about when the draft bill would be made into a law. It had happened in Maharashtra after Dhabolkar was murdered. In Karnataka Kalburgi had been killed. I asked them: How many more of us do you want to sacrifice before this legislation is enacted?” I feel sorry now that my words were prophetic: the cabinet has now approved the Bill after the ghastly murder of Gauri Lankesh, one of the first to ask for the passing of the Bill. It is ironic that she is not here to see the success of her efforts.

In a land where religion takes precedence over so much else, this Bill seems to bring a glimmer of hope. The Bill plans to tackle Bhanamathi — allegedly a type of black magic practised in Hyderabad. But though I have been campaigning against it for more than two decades, I am yet to see anyone who practises it. We see only the victims. The fear of this “magic” is such that people do not even mouth the word. One good feature of the Bill is that it seeks to address indignities against women such as ostracisation, segregation during menstruation and pregnancy, or parading them naked in the name of worship. There is, however, the possibility that if such practices are claimed as part of religious tradition, they may be exempted. Astrology and vaastu, not scientific by any stretch of the most fertile imagination, are exempt. The government itself encourages non-science in the name of traditional beliefs without the need for evidence. For example, homeopathy, which is being encouraged, would really qualify as a superstition since there is no evidence of its efficacy. Suicide by starvation (the Jain practice of sallekhana or santara) is exempt. Again, the propagation of so called miracles of dead people would not be an offence. For example, it would not be an offence to claim that the dead Puttaparthi godman is producing things from thin air; or that Jesus Christ converted water into wine. Again, circumcision and female genital mutilation would not be offences as they are “accepted” religious practices.

Given all these inadequacies and loopholes, much work remains. That a vigilance officer will monitor the provisions of the law, and the government will seek to identify violations appears to be a welcome move. But how it works remains to be seen. The punishment also appears modest — imprisonment for not less than a year and a fine of Rs. 5000.

At the same time, one central point remains for discussion. Can superstitions be eradicated by legislation? My own answer is a vehement No, because no legislation can substitute for education.

What would be a better solution to the problems of superstitions in a country like ours? The answer would be education – but in the true sense of the word, and not the literacy passed off as education today. Teaching the younger generation to think rationally, and question received wisdom before accepting it would be the best solution. We have engineers, doctors, lawyers and scientists who are literate, or rather knowledgeable in their own subjects, but who do not think rationally about what they encounter in the other aspects of their lives. We have astronomers fasting during eclipses, doctors who believe that the application of holy ash will cure disease or that the blessings of a holy man are necessary for a successful surgery.

Article 51 of the Constitution of India defines the duties of the citizen. One such duty is to develop scientific temper, the spirit of enquiry and humanism. The implementation of this duty should be our real aim. We must work for this constitutional duty of every citizen prevailing over minor legislations such as the Karnataka Prevention and Eradication of Inhuman Evil Practices and Black Magic Bill, 2017.

Also read:

The Cursed Practice of Made Made Snana

By Narendra Nayak:

The Claimants of Supernatural Powers in Rural India

Blind-Folded Seeing: Turning “Average” Kids into “Super Geniuses”