“The length of patriarchy is its greatest strength, its seeming permanence; its pretensions to a divine or natural base have been repeatedly served by religion, psuedo-science, or state ambition. Its dangers, and oppression are not easily done away with. But surely the very future of freedom requires it not only for women but for humanity itself”

Kate Millet (Sexual Politics, 2000, xiii)

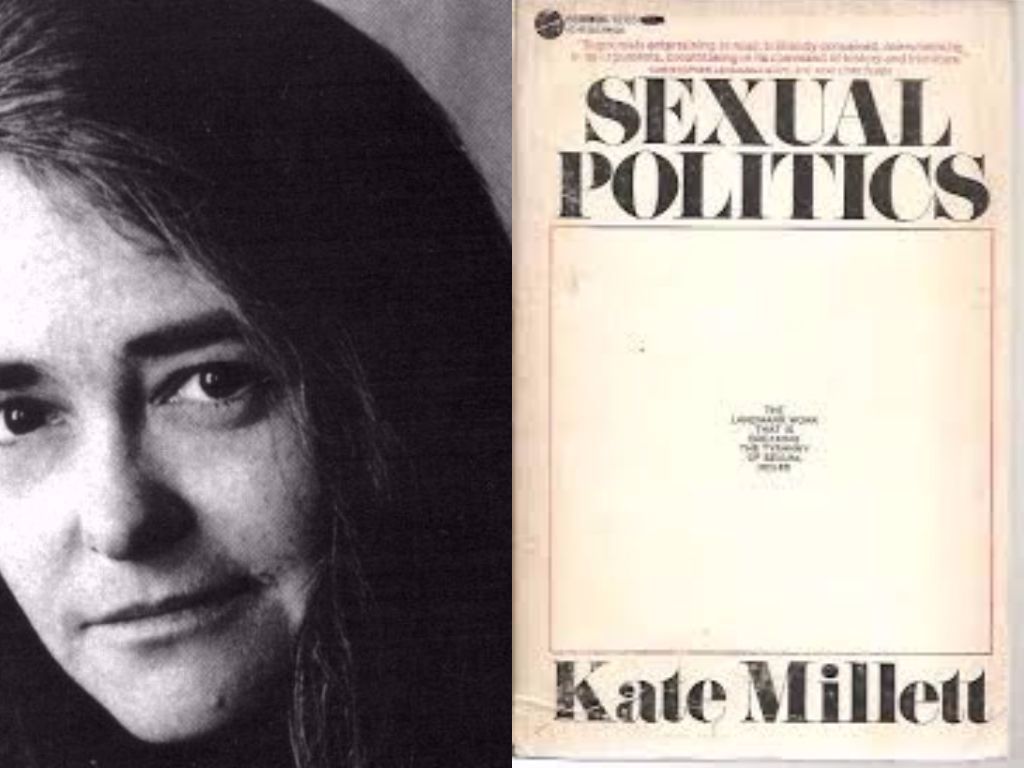

Kate Millet was an American feminist writer, artist, educator, and activist. The well-known feminist classic Sexual Politics was her doctoral thesis and her first book. Sexual Politics politicises sex. Sex was always considered a sacred function of procreation, and Millet argues that this logic of procreation has been abused by masculinist power for years; using it as a garb to hide and suppress the fact that sex is also a powerful agent of patriarchy. As an agent of patriarchy, it defines an authoritative “male gaze” that characterises the “feminine”, and further buttresses the violent and exploitative structure of patriarchy. The apparently innocuous nature of sex as an isolated sacred function of procreation has, since time immemorial, cajoled us into ignoring sex as an agent of patriarchy. Kate Millet, in Sexual Politics, presents a sharp analysis of writing about women, writing about men, and writing about sex between them. Sexual Politics sets a framework for feminist writing on the politics of sexuality.

Writing about sex would not have been an easy journey at all. Millet also speaks about the “quiet censorship” that she underwent when the book went out of print, and no one else was ready to re-print it. She notes that this censorship was an effort of the “vast corporate conglomerates controlling the American publishers” to end the circulation of “thought provoking books” (Sexual Politics, 2000. Page number: x). Nevertheless, she also very fondly remembers her first publisher Doubleday; their trade section had informed her that Sexual Politics was one of the best books that they had published.

Ritu Menon, an Indian publisher, writer, and a feminist, recollects the first time she heard of the book Sexual Politics; she was working in the market research department at Doubleday, in New York,1970.

I was working at Doubleday, in New York, in their market research department, when we were told by Betty Prashker, one of their senior editors, that Doubleday was going to publish a book called ‘Sexual Politics‘. Loud guffaws from the guys in the department. “The author is Kate Millett”, said Ms. Prashker, “and this is a very important book”. Sniggers. I was intrigued. It was the first flush of the women’s movement in the U.S. New terms like “consciousness raising” were in the air, and already Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique had swept through academia and the market. Still, it was early days and the marketing guys were sceptical. But Betty Prashker was right. Millet was a huge success, sexual politics became part of the language and of everyone’s vocabulary, and my consciousness was raised sky high! My one regret is that I never met her, as the editorial and market research departments at Doubleday could as well have been on different planets!

The text inspired many feminists, queer activists, whose subjects were oppressed and suppressed by the patriarchal system. Kate Millet introduced a new perspective to patriarchy. Sexual Politics also inspired young activists across the globe, including those in India. 1970s was the period in which the womens’ movements in India were fighting against various forms of violence. These movements were also involved in legal battles, fighting for gender just laws. The infamous ruling of the Supreme Court of India in the Mathura rape case had triggered movements against the ruling. Mathura, a young tribal girl was raped by Ganpat and Tukaram, two policemen on the compound of Desai Ganj Police Station in Chandrapur district of Maharashtra. This movement had led to the amendments in the existed laws against rape.

V Geetha, a well-known Indian scholar working on feminism and caste, remembers reading Sexual Politics in 1980s in the then existing culture of student politics in India. The gendered nature of this political culture, Geetha notes, had drawn her to the text:

The American “second wave” was what my generation missed and got to know second-hand, from older women friends, who were completely seduced by Sexual Politics, and to a lesser extent, The Feminine Mystique. I did not read these texts when I first heard of them, though. I was fascinated but not interested enough. Student politics in the early 1980s proved overwhelming and one’s incipient feminism was put to everyday use, trying to outwit fellow male students who imagined that girls who wished to participate in student politics ought to learn their place. However I did manage to read Sexual Politics not too long after and was mesmerised by the sharp, critical, and yet, assured manner in which the book tore into male literary self-consciousness.

I remember being overwhelmed by Millet’s critique of Tolstoy, who I was reading avidly then, in fact had just finished Resurrection and her merciless foregrounding of his masterly disdain for women made me angry, at him; at myself for liking his work so much. However I don’t remember being particularly influenced by Millet thereafter. Coming to feminism in the 1980s, in the Indian context, was heady enough, and there was so much to absorb and learn that texts such as Sexual Politics remained at the fringes of one’s consciousness.

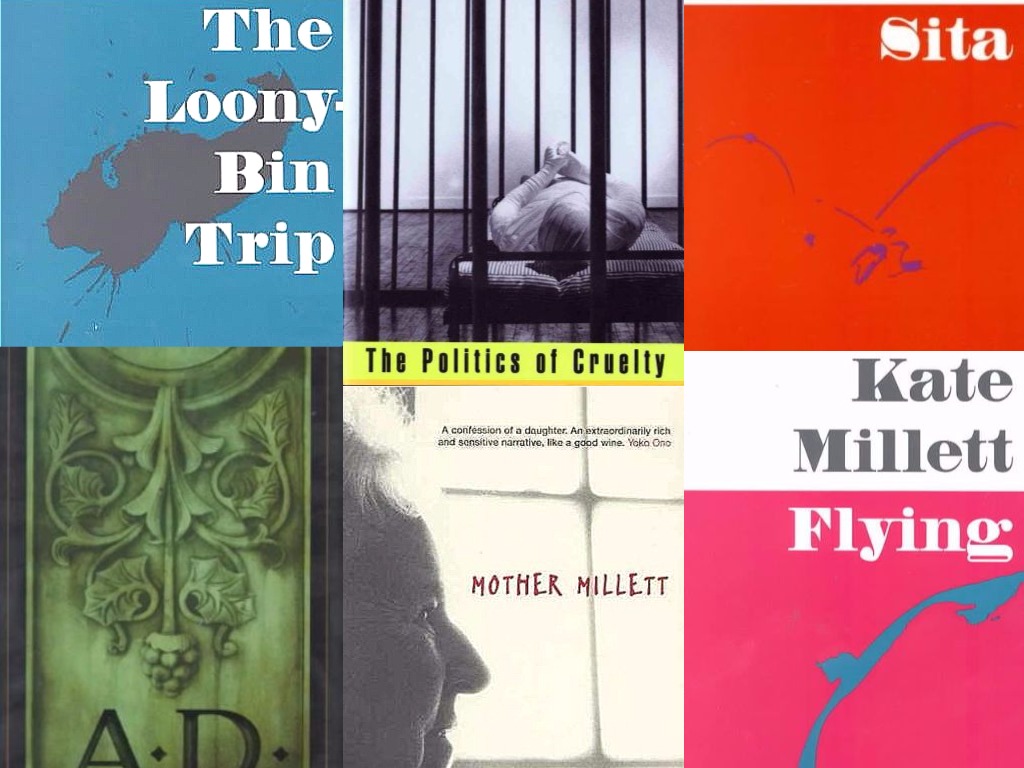

Subsequently, I did keep up with Millet’s work, having gone back to read all the classics of second wave feminism while working on matters related to domestic violence. At that time, it was Catherine Mackinnon that I read though, and only fleetingly referred to Sexual Politics. What made me turn to Millet again is a book that is very little spoken about, but which I think is one of her best, The Politics of Cruelty, which is about the relationship between writing and incarceration. I learned a great deal from it, and used it extensively in my own work on the relationship between caste, violence and religion. It seems to me that in this book, Millet returns to her earliest concerns culture, literature, voice, and narrative. She sees what men do and represent but examines each of these using the lens of political violence, including torture. I’d say it is this ‘twin’ of the classic, Sexual Politics that has stayed with me.

Some well-known titles by Kate Millet/ Image courtesy Yogesh S