In my stories I’ve put down everything with objectivity. Now, if some people find them obscene, let them go to hell. It’s my belief that experiences can never be obscene if they are based on life. These people think that there’s nothing wrong if they misbehave behind the parda… They are all halfwits.

Ismat Chughtai

Ismat Chughtai was born a rebel, and became an iconoclast. As a girl at the turn of the 20th century, she was expected to conform, but, she was determined to do all the wrong things: get educated, leave home and study in Aligarh, not get married, and tauba, tauba, never learn how to cook! When her mother asked her in despair, “Then who will marry you?” she replied calmly, “I’ll marry a man who knows how to cook.”

The facts of her life are well known: Inspectress of schools, an active member of the Progressive Writers Movement, scriptwriter for Hindi films, co-producer and co-director of several films with her husband, Shahid Lateef—and a prolific writer of dozens of short stories, three novels, four novellas, plays, essays, reminiscences, and an autobiography, The Paper-thin Garment.

Her writing was fast and furious, almost as if her pen couldn’t keep pace with her thoughts. Often, she rewrote her stories more than once, not in the least put out by the different versions that appeared in print. She was supremely detached from what she wrote once she had written it. When I asked her if she could give me a copy of “Zehar ka Pyala” which we wanted to include in an anthology of her stories, she declared she didn’t have it! Didn’t have copies of anything she had written, she added nonchalantly. I thought she was being mischievous, as usual. But, no. “Nanhi,” she said, “afsane sikke ke mafiq hain, jitna ghumein, utna accha.” (My dear, stories are like currency, the more they circulate, the better.”

In these days of copyright and intellectual property, her complete disinterest in owning her work is remarkable.

Well known, too, is Chughtai’s lifting the veil on female sexuality in her writing, and on the hypocrisy of the Indian middle class, as well as her sharp, yet sympathetic, portrayals of human frailty. She is surely among the first of our major writers to put women at the centre of her stories, to make the zenana her site, but to yank it out of the domestic and private and place it, squarely and unabashedly, in the public. “Lihaaf” may be her best known story, but you have only to read “Terhi Lakeer” to realise how radical it was when it was written.

Less well known, perhaps, is Chughtai’s preoccupation with the role of literature in society; her belief that literature changes lives more than pamphlets can. But she also knew that the enormity of some events like the Partition of India in 1947 can temporarily render literature speechless. When it found its voice, however, “the pen thwarted the attacks of the knife and dagger”. Writers like Krishan Chander, she says, “set up a veritable fortress and sent an army of afsanas, stories and sketches into the field. The speed with which the riots spread, was matched by the speed with which Krishan’s afsanas were circulated in both Hindustan and Pakistan.”

She confessed, however, that “I’m at a loss with what to do with “Siyah Haashiye” (Manto’s “Black Margins”). Should I catalogue it as a work of literature, or should I find an entirely new classification for it?… Manto has managed to receive a lot of applause, but the arrow has missed its mark this time. Surely Siyah Haashiye is neither a masterpiece nor a timeless marvel.”

In retrospect, it should not surprise us that Manto’s Partition stories are remembered more than Ismat’s own, very powerful “Quit India!”, or “Roots” or “My Child” — or even the two plays she wrote on Hindu-Muslim riots, Fasaadi and Dhaani Bankein. For, although ostensibly about the violence that followed India’s independence, her real subject was Hindu-Muslim relations, whether before or after Partition.

On the 70th anniversary of both independence and Partition, it is worth recalling that Ismat Chughtai batted for renewal, not rancour. Her stories are an affirmation of that hope.

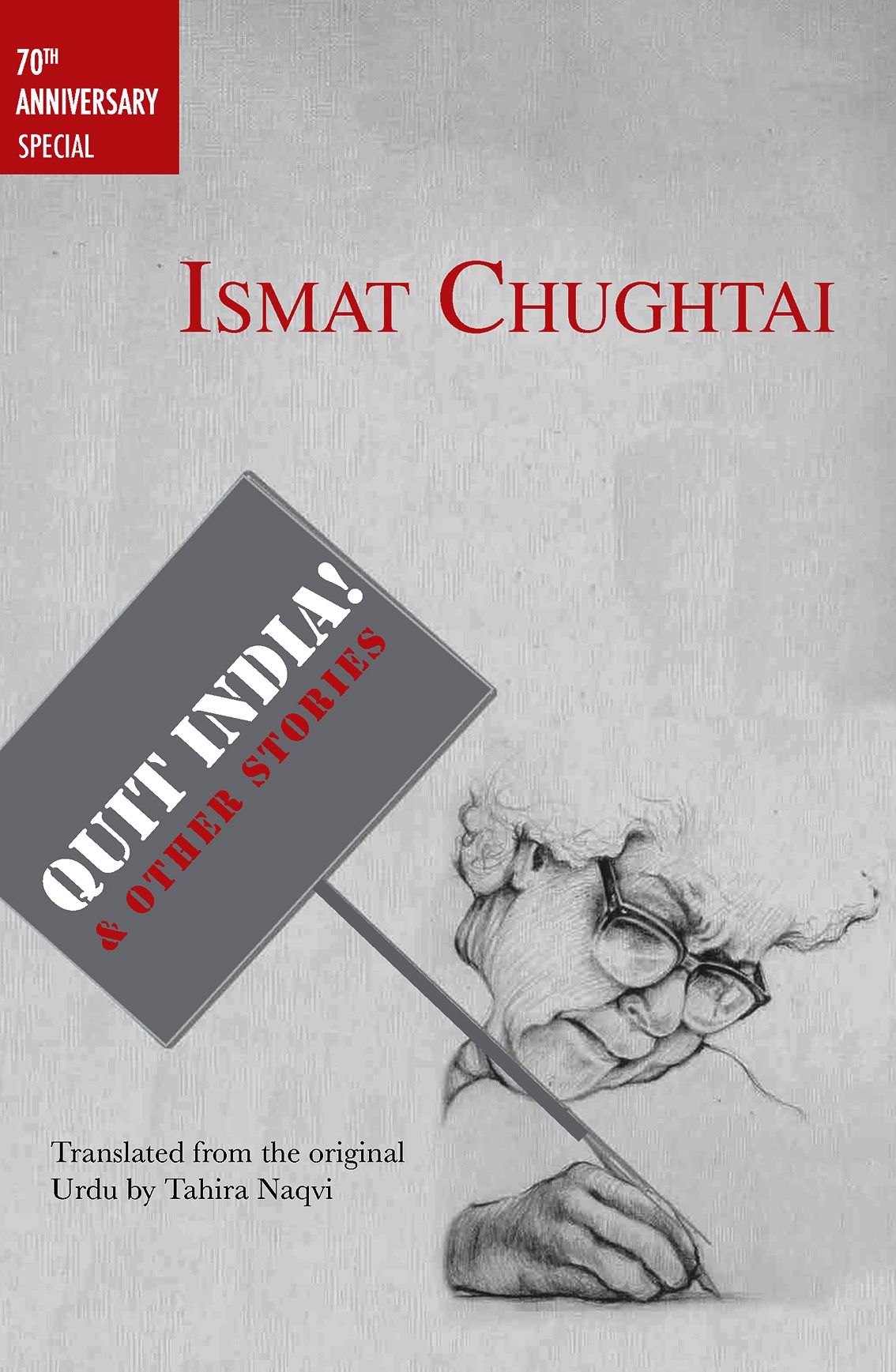

Read Ismat Chughtai’s story, excerpted from a new anthology Quit India! and Other Stories from Women Unlimited, and translated by Tahira Naqvi here: