When interfaith marriages took place in the upper classes and among families of equal status, the parents usually kept quiet. The children of these couples were given indistinct names like Kabir, Rahil, Samir, Mona or Seema, or Russian ones like Mira, Zoya, Natasha. Eid and Diwali were celebrated as cultural occasions in their homes.

When Qambar Ali came home for lunch, he brought up the subject of Sharbari. “Sharbari was very annoyed today.”

“What happened?” Barrister Ali asked.

“Miyanjan, she teaches modern Literature to the MA class in the Department of English. Two of her students have got married and come to class with a lot of vermilion in their hair. Sharbari has been teaching them Sartre. She told them that they would never be able to comprehend Sartre if they used so much vermilion.”

Barrister Ali smiled. “What is the connection between vermilion and Sartre?”

“Miyanjan, vermilion is a sign of the enslavement of Hindu women, a symbol of superstition. Among us, it is glass bangles and in Hyderabad, glass beads. In the south, it is the mangal sutra.

“Beta, for married women such things hold great importance,” Bitto Begum said.

“Why don’t men wear anything then? If nothing else, they could wear a safety pin in their noses. Sharbari told these girls to wipe off the vermilion or she wouldn’t teach them Sartre.”

“Hai hai, asking a married Hindu woman to remove the vermilion from her hair! This Sharbari of yours sounds crazy, and she herself is a Bengali Brahman.”

“Ammijan, women when they become widows have to break their bangles and wear white. Are all symbols meant only for them?”

Barrister Sahib kept smiling benevolently.

“One should respect one’s cultural traditions if they do not do any harm,” he said.

“Isn’t vermilion harmful? How can a woman wearing it have a modern mind?”

Shaikh Sahib was very amused. After finishing his meal, he left for the courts. Bitto Begum then asked her son, “What is going on with this Sharbari?”

“She . . . is my co . . . comrade.” Qambar would begin to stammer slightly when he was nervous.

“Any plans of marrying her?”

“Not at all, she is too argumentative.”

“Shall we look for an intelligent girl for you? One who doesn’t object to wearing red glass bangles?”

“Sure—but on two conditions. One, she should be highly educated and two, she should be from a poor family … and three, she should be beautiful.”

“Will we be allowed to decorate the parting in her hair with glitter on the day of the wedding?”

“O…kay, but she shouldn’t wear a nose-ring like cattle at the time of the nikah. That is a symbol of the enslavement of women.”

“Mother and son are turning our home into the Sabarmati Ashram! What should I now say to Anwar Hussain? Bhawani Shankar, show me a way out.” Barrister Sahib said to munshi Sokhta. “Now listen to this! Begum Sahib is going to Zafarpur today in search of a poor girl.”

“Is there a shortage of them here?”

“She says charity should begin at home.”

*Alima Bano was a childhood friend of Bitto Baji’s and had been extremely unfortunate. Hers was a familiar story—her husband had gone to Pakistan and divorced her from there. Alima Begum had finished school before her marriage and then earned a BA, BT. She taught in a school and got her daughter to finish her MA, and B.Ed. mother and daughter lived in the town of Zafarpur in the two remaining rooms of their dilapidated ancestral home and were teaching in a private college. The owner and principal of the college made them sign receipts for a hundred and fifty rupees while she handed only eighty rupees each to them.

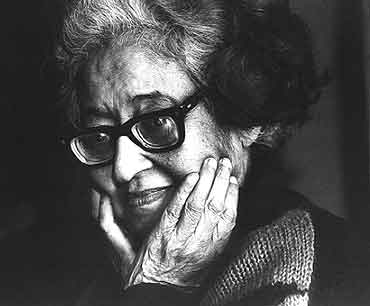

…Bitto Baji was seeing the girl for the first time after she had grown up. Very sweet-looking. However, there was one drawback. The thick-lensed spectacles she wore covered practically half her face. Well, even the moon has its blemishes. Qambar Ali himself was no oil painting.

“Sister, what can I do. I have always been short of money and the electricity supply was disconnected. She had to study by the light of a lantern, and that ruined her eyes.”

Bitto Baji kept quiet. The girl was appropriate in every way. She met all three of Qambar’s conditions. Apart from this, as she was from a poor family, she would be submissive. When Bitto Begum returned to Lucknow, she showed a photograph of the girl, in which she was wearing a gown and holding a rolled up MA degree, to Qambar miyan. She had taken off her spectacles for the picture. She struck Qambar the moment he saw the picture. “This is just the sort of girl I wanted! Highly educated and from the working class.”

“Yes, she is working class. An educational shark, masquerading as a college principal, has been economically exploiting the mother and daughter and many other teachers like them.” Bitto Begum began to make a speech yet again. “In the next issue, you must also write a strong note about this racket in educational institutions.”

“For sure, Ammi, and at the first opportunity I will also come to Zafarpur with you. I will meet this brave, courageous fighter and if I like her—and why shouldn’t I—I, I will ma … marry her too.”

Barrister Azhar had entered the room. After Qambar Ali left, he asked his wife, “What was this rubbish that the two of you were talking about?”

“You just watch. Right now it’s a good way of distracting him from Sharbari devi.”