Sova Sen, the legendary actress of Bengali theatre and cinema, passed away five days ago, on 13 August. Sen joined the political theatre of Bengal after she passed out from Bethune College. With these excerpts from Himani Banerji’s essay, based on her interviews with Sen, we begin a series of tributes which critically evalute Sen’s contribution to the political theatre of Bengal.

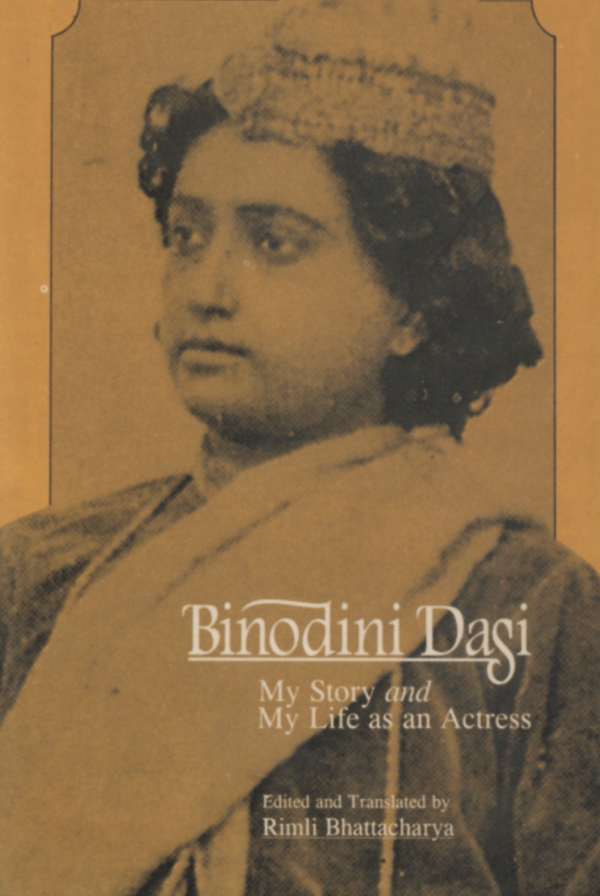

Since Binodini’s time, the theatre world has grown much larger and now, essentially, consists of two separate tendencies. First, there are the commercial theatres companies (which are businesses where directors and actors are employees). These are the more direct outgrowth of the tradition of the public theatres. This the business of entertainment.

But there are also ‘group’ theatres; these are ‘amateur’ groups where no one is paid, though they produce regular shows in halls with tickets. Group theatres numerically, as well as culturally, outbid the commercial theatre. This is the world of theatre as ‘art’; theatre as education. Social and political consciousness-raising, as well as formal experimentation, are on their agenda. This theatre owes its existence to the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was created by the Indian Communist Party (1943) in order to link theatre with politics. The IPTA was eventually fragmented on lines of aesthetics and politics, which led to the traditions of gananatya (people’s theatre) and nabanatya (new theatre) – gananatya leaned very heavily on politics, while nabanatya was more concerned with psychological and formal experimentation. Though a rigid distinction between the two is not always possible, the group theatre movement of today includes both tendencies.

The acting environment of group theatre is quite unlike that which preceded it. The actors and actresses come from the middle class, and, very often, have some kind of left/progressive political consciousness. In order to understand the position women hold in the theatre, I spoke to Sova Sen, the most dynamic actress in the group theatre movement. Her acting career began with the first notable performance by the IPTA in 1943. She has remained in the theatre world through thousands of nights of acclaimed performances.

Sova Sen’s contribution to political theatre has continued unbroken since 1944, but she is also important for us because she has struggled both on personal and political grounds, and has emerged triumphant. Her mere presence in the theatre as a woman during the forties -– combined with her divorce and the fact that she was already a mother at the time of her second marriage – created many difficulties for her in a society that continues to be semi-feudal in many ways. Her contribution to Bengali theatre consists not only on her impressive acting talent. Along with Utpal Dutt, the playwright, director and actor, also her husband, she has built and maintained two major theatre groups: Little Theatre Group (LTG) and People’s Little Theatre (PLT). The latter is also the largest and most accomplished of Calcutta’s theatres.

Sova Sen and I began by talking about the differences in the social perception of actresses between the time she entered the stage, and our present time. Although things are somewhat better and easier in the group theatre movement now, these are still difficult times, she said.

The major obstacles for women in pursuing their acting careers are some traits in the character of the Bengali middle-class males… They may think of these traits as virtues, but we think they are vices. With those prevailing attitudes, it is very difficult for women to come out and associate with the world outside – the world of cinema and theatre, and the cultural world at large. I faced these problems myself, except that I had an advantage. I entered the world of theatre with a political idealism – I was associated with the IPTA. So wherever we went, we were respected for that. But I have noticed that other actresses who were on par with me as actors, who could not even survive the harassments…

Ever since my childhood I had an ambition to overcome the hazards and obstacles put in the path for women. In doing effective work in the world outside, I felt that I would rise above the distrust that men have towards women and prove that women can remain “good” and yet work outside…

And about being “good” or “bad” – who defines what’s “good” anyway?

It helps to come from middle-class homes, be educated, and have a political idealism. However, it also seems ‘cleaner’ if these actresses are economically independent of theatre…These financially independent actresses are not socially ostracised for doing theatre.

…On the other hand, Sova Sen also drew my attention to the fact that the respectability of group theatre has its own burdens for women. The family’s ‘normal’ expectations of a female member continue unabated. Whereas the older actresses could see this as their major ‘job’ and devote vast amounts of time to the theatre, the new actress’ choice is taken far less seriously – both by her and her family. When she is awarded the honour of wifehood and motherhood, she has less legitimate time for acting. Family continues to be her first priority. Sen says,

There will always be struggles and hassles in the theatre movement, particularly for women. Take, for instance, the problem of finding women for the characters. We ran Minerva Theatre professionally and we were bugged by this problem all through. There are two ways of getting actresses. Some women come with some sort of idealism. Others, just to take a chance – if you become a member of Utpal Dutt’s group you may get a chance in films. We did get some women who fought every obstacle to get here, but they couldn’t carry on for too long. They had to leave because of all kinds of family problems…

Theatre could neither produce nor solve these social problems by itself. Sen located them in the prevailing gender roles, which, she felt, was organised through class structures. At one point, she contrasted the world of poverty and social respectability of middle-class women with working-class women:

Women of the peasantry, of lower classes, don’t put up with as much (gender based) abuse as women of the middle-classes. They have an economic quality with men. They earn almost equal amounts as men, working side by side with them. So if men oppress them – if they hit her – she has the option of hitting back. They don’t have as much at stake in things like property, dowry, and respectability. They can break their home and leave. But middle-class women are torn with doubts and conflicts: what will people think of me if I leave? Who will feed my children? Who will feed me? Maybe I’ll end up in a worse place…

You see, feudalism still thrives in our society, particularly among men. They are brought up with such protection and service! A boy doesn’t even have to fetch a glass of water even among the working class. It is always a woman who has to start her household chores after she comes back from work. Everyone accepts this! It’s considered natural. If a husband enters the kitchen people are shocked. What! You are cooking? That is unthinkable. These attitudes, regressive traits within us – if we can’t get rid of them, sweep them clean, nothing can help women.

The subordination of women, the asymmetrical social relations which produce such strict gender-based expectations, rise from everyday life, enter the stage, and recycle back into life. From the late nineteenth century to now, the image of the woman, of male-female relations, of family relations, have not changed much in theatre or film…

Bengali theatre tradition is replete with the myth of all-sacrificing motherhood. The female lover, on the other hand, oscillates between the rhetoric of revolution, and the sweet saccharine of ‘true love’. The dialogues, the inflection, the gestures, often make it hard to believe that these plays are produced with the intent of revolutionising the social unconconscius of the Bengali middle-class.

‘Where,’ I asked Sova Sen, ‘do these roles originate from?’

‘Partly from life,’ she replied, ‘and partly from their fantasies.’

‘But do middle-class Bengali women ever behave in this way?’

‘No, they do put up with a lot – they are forced to – but their struggle is not so visible. After all, how many of them are economically independent? Without that it’s almost impossible to put up a fight… She may say many things, but ultimately she returns to that bedroom. Our playwrights, who are male, observe us. They see most of us put up with a lot. I think it pleases them because they are men themselves. Men take their wives to plays like Don’t Wipe My Vermilion. They want women to see this. They want us to see how patiently women should serve their masters…’

But Sova Sen’s roles are different. Some of them are quite repugnant to the sensibility of the middle-class. Sen insists that she has never been typecast:

I didn’t have to face the fact that I will be cast as a type because Utpal was the playwright. He wrote the plays based on his knowledge of me, and my acting abilities. He is also the director and actor. He understands my potential better than anyone else. So he shapes the parts according to that knowledge.

The role I did in Kallol was great. She is a Maharastrian lady who defies her son to protect her daughter-in-law who’s living with someone else. ‘Okay, she says, ‘you went away to war. You didn’t think about us. You didn’t know, or even cared to know how we lived. Now, if you’re wife is with someone else, it is because she had to live when you were away. She can’t be blamed for that. Who gives you the right to turn up now and challenge her?’ You know, she is also an old lady and she joins hands with the revolutionaries…

Now here’s a woman who fights with her son to protect another woman (her daughter-in-law). We have to see this as a very big event in our theatre history.

Sova Sen’s portrayals of women, both in dialogue and performance, may retain some of the traditional features (for example, the convention of motherhood), but she rids the characters of their passivity. She emphasises toughness, heroism, and introduces dynamism to the roles she portrays. There are also, quite often, conscious satires of men’s expectations of women.

Probably in a conscious tribute to actresses such as Binodini, Utpal Dutt wrote the play Tiner Talwar (‘The Tin Sword’). Sova Sen played an actress for whom the stage is the highest priority. In the play, both she, and a younger character, scorn marriage and family life in order to live as actresses, as artists. This play, and a few others, brings together the old and the new in a revolutionary reversal of social attitudes.

Our conversation testified to these changing values. Sen showed immense respect towards actresses who come from the lower walks of life:

When I first joined films, I spent a lot of time with these actresses. I received such affection, respect from them; they trained me. Some of them wept when they revealed to me that their children could not enrol in schools. I was amazed. What crime did these women commit?

…With her characteristic astuteness, Sova Sen pointed her finger at the economic vulnerability of women. She gave an example of theatre as business:

You must keep this in mind. You must ask, who runs these shows? Behind each venture there’s a huge, fat capitalist. Some are into steel or iron, others into something else – all have pots of black money. Playwrights produce what these financers demand. After all, in our country, no one can live by writing plays alone… People don’t read plays. They just see them. They have to lick the boots of these owners. They have to make a living.

Sova Sen felt that for any real change, for a reorganisation of theatre on non-gendered and non-commodity basis, there would have to be fundamental struggles on the lines of class and gender. Changing the relations of inequality is going to be a large struggle. As a Communist, she was partisan in her long-term approach. In the short run, however, she agreed to my suggestion of an actress’ association or a union that would deal with both the problems of economic insecurity and sexual harassment. She suggested there should be an economic angle too:

Actresses resort to begging in their old age. They become a burden on their families, if they still have them, that is. Actors, actresses, and playwrights must unite in their struggle and try to solve these problems of making a living collectively. That might work. Some people are already working for this to happen.