The first time we met, in Mumbai—still Bombay in our common parlance—towards the close of 2003, Vijay Nambisan showed me the paraphrase of a Tamil Sangham poem, along with his own English rendering of it. I remember sitting next to him and reading it—on a blank page improved matchlessly by Vijay’s cadenced hand, etched in common royal blue. He had given that sheet of paper to me as though he were handing me a rare miniature. Even as I returned it to him, it stayed with me.

Even without crediting the beauteous measure of his act of sharing it with me, Vijay’s poetic trans-creation of that brief Sangham text remains one of the most politico-aesthetic and ethical illustrations I have seen of someone interpreting an other time for his/ her own. So, a few months after our meeting, I asked Vijay for permission to use his work in a paper titled “Aesthetics of Dynamic Translation”. He asked me where and in what context his work would appear in my paper. The play of control and nervousness in his queries at once astonished and amused me. Yet, I answered him with the gravitas he expected, and then he said, with immeasurable camaraderie and trust, that I could use his work anytime. Years later, when I read “A Little Better”, I knew, he had always been that “little green thing”, and that he knew it:

And so this little greenling sits

In the sun, satisfied with itself,

Whatever it is. (“A Little Better”)

And, I gratefully share with the readers here, Vijay’s trans-creation in its little entirety, of the delectable Sangham spirit, dedicated to Gauri Ramanadhan who sang the original Tamil poem for him.

Paraphrase:

Sweet parrot in prison, come here, I will give you milk and honey to eat. Speak just once for me the name of the Lord of the city of the shining young crescent moon on the shores of the ocean where boats come to rest, laden with corals and pearls.

Vijay’s transcreation:

(For Gauri)

Parrot,

green parrot,

green parrot in a cage,

speak to me

and I will give you honeyed milk

to keep sweet your tongue:

speak one word to me.

Moon,

hornèd moon,

Lord of the hornèd moon,

Lord of the city of the hornèd moon

by the refulgent sea:

parrot,

sweet parrot,

sweet parrot in a cage,

speak His name to me.

Look at the classical dance of words on the page, but also listen to the alternative music that this poet creates with the English sounds. Behold how confidently he contains the ocean, the shore, the boats, the corals and the pearls in a single succinct phrase, “refulgent sea,” and yet how urgently, almost school-boyishly, he adds that the parrot needs a sweet tongue to speak the name of the Lord, lest anyone missed that critical point!

I consider it a grace that Vijay Nambisan offered me such an early chance to see how the politics, aesthetics and ethics of his engagement with words possessed a certain vulnerability whose only match was their integrity. Later, it helped me understand why he seriously wished to interact with young people about language as ethic and wanted me to organise a talk at a University, but on the day of the lecture, landed there in an inebriated state. From “Madras Central” till “First Infinities” this poet thus remained between two intense measures, just as the man lived between the two complete states of intoxication and sobriety.

All the world, it seems, knows I like to drink;

How few know how well I like to be sober.(“To Have Been Written in Urdu”)

This curious knowledge about the co-existence of the self and its other in the being of the human was what allowed Vijay to see the possibility of renewal everywhere. He minded no “man-measures” of lucidity, but discovered fire every time, without the weight of established memory. He was always a first Christian, a beginner of infinity.

It was that keen insight into the secret of birth, again, which let Vijay grin at the opinions of his line of critics through a circle of smoke, and nonchalantly accommodate two different measures of Bhakti, that of Poonthanam and Melpathur, within the covers of one book, with a linking poem by Vallathol Narayana Menon on the relationship between the Namboodiri’s faith and the Bhattathirippad’s erudition.

Eunice de Souza, who passed a little before Vijay, for instance, in a scathing review of Two Measures of Bhakti (2009), made it clear that she had no patience for his (seemingly) contradictory introductory comments in the book on Malayalam literature vis-à-vis English and Sanskrit literatures:

“It’s all so bogus. Nambisan should start writing in Malayalam, never utter or write a single word in English again, and spare us his immaturities. There’s too much of this crap around already.”

I deeply respect Eunice and her work, and also understand her fury about Vijay going “overboard” (I am concurrently reflecting elsewhere on her own engagement with language as ethic). And, I would also not claim that Vijay was in his communicative best in his Translator’s Apology. Yet, how I wish Eunice had reminded herself of the structure of Gemini (1992), where two young poets as different as Jeet Thayil and Vijay Nambisan were linked by the older Dom Moraes, before tearing Vijay apart for apparently joining the self-pitying bandwagon of the native-language-championing abusers of Anglophones. Had she recollected that coming together and seen its metaphorical significance, she would have certainly figured out how Two Measures, with its confident ambivalence, had absorbed the body of Gemini into its own spirit. But, Eunice thought she upheld an ethic different from Vijay’s, and, the self-satisfied little green thing that he is, he never bothered to clarify beyond what was already written.

Vijay’s extraordinary faculty to see the neighbour and himself as self-other/ other-self lent him the sprezzatura – with which he did intense translations of devotional writings from the little Tamil Sangham poem to the long Jnanappana (Malayalam) and Narayaneeyam (Sanskrit), while remaining an agnostic. His integrity was curiously revealed in his knowledge and acceptance of the division inherent in the human condition, which made him naturally daring to translate from languages that he apparently did not read or write well, but knew profoundly as ethical complexes where reflection, expression and communication play with one another. And this was his hope for the future:

In some world to come

Each house shall be only the threshold of the next. (“Neighbours”)

Hence, the neighbour, with whom he co-existed, mattered deeply, and yet did not matter at all, like poetry. For, it was that other, who showed him the possibility of renewing himself, of being reborn.

In “Dvija”, the longest poem in First Infinities, an encounter with the ghost of the narrator’s father that reminds one of Hamlet, Vijay discards the word’s caste-based meaning (dvija, literally twice born, is a synonym of Brahmin), and employs the idea of the second birth to think about how one might live on in the dreams of others. And like Hamlet, he seems to be convinced that “readiness is all”.

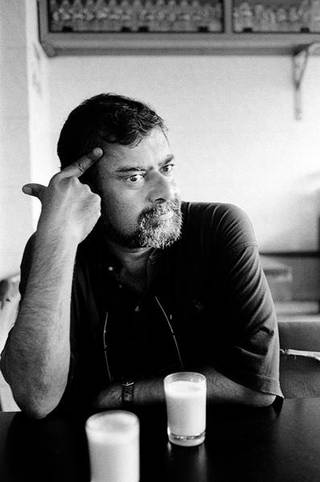

With his passing, and everyone writing about Vijay Nambisan, the facts of his supposedly reclusive social life are all out in the open. He had long been fashionably dubbed a recluse, but those who have met Vijay would know that he was no depressing loner. He was a warm, modest man, who loved engaging conversations. He drank himself to death, but was so conscientiously sober when one sat and talked with him.

Yet, it looks like he has reversed himself as he went from our midst. For, whenever he reversed himself, he was letting his other in each of us reverse herself. So now, the questions and convictions that he carried seemed to have fallen on us.

And we may ask, like Vijay Nambisan: What will keep our languages blessed and alive, and not make them sacred and dead?

And, we may discover our own fiery little tongues, like him, by sanctifying all our languages everyday “by common and pious use”.

And, someday, we shall overcome, and find the true vijay of our greater common good!

***

Further reading:

Translations by Kanupriya Dhingra: “The newly dead is an unknown quantity”: Remembering Eunice de Souza

By K. Satchidanandan: “Without My Imaginings What Is?” Remembering Vijay Nambisan

By Nabina Das: For Eunice and Vijay