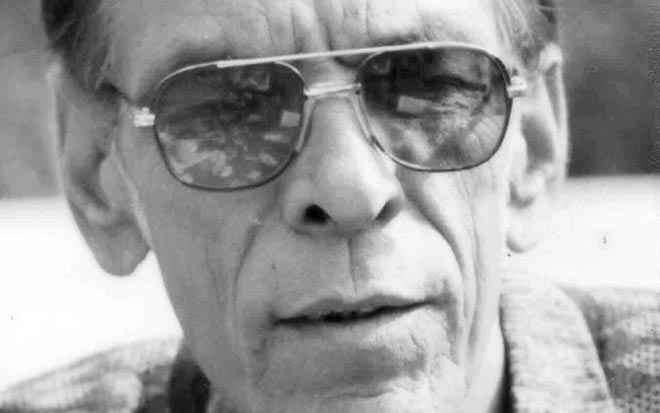

A remarkable pen has been stilled. With the passing of Naiyer Masud (1936-2017), Urdu literature has lost its most ambiguous voice. And with him, gone are answers to many questions that have long bedeviled his many admirers. How can we best describe Naiyer Masud is a question that has always been raised in literary circles. Was he a modernist or a post modernist? Was he a writer of fantasy or surreal literature? Masud himself acknowledged the influence of Edgar Allan Poe, and was among the first to introduce Urdu readers to the writings of Kafka through his immaculate translations into Urdu. A scholar of Persian and Urdu, a former Professor of Persian at the Lucknow University, Masud was a lifelong avid and eclectic reader living in a house that was filled, appropriately enough with books and relics of the past and was called, equally appropriately Adabistan (the Abode of Learning). The range of his reading was reflected in his writings. It is this range that made him difficult to categorise. He also took special pains to create a landscape that was unfamiliar, unrecognisable and uncategorisable. He did this by a conscious, deliberate purging of idiom, and by a language that was measured and precise. As Masud himself wrote, “I don’t want my language to give away, however obliquely, the temporal identity of my characters.”

No other writer would work so hard at revealing things as Naiyer Masud did in concealing them. Despite all this, he had a penchant for profuse and relentless detailing, a precision and clarity of writing and expression, and an eye for the tiniest of detail! In his refusal to make things easy for the reader, Masud requires a close and attentive reading. He pulls you in with all the tenacity and insistence of a dream, despite its blurred outlines and disregard for time and space. Such is the mesmeric pull of his writing. Part magic realism, part Kafkesque, once you are inside inside his world, there is no escape. There is something so seductive, almost hypnotic about this collection of stories that the conventions of story-telling, such as plot, character, narrative, become meaningless; the word and suggestion is all.

Masud was especially fortunate in finding a skilled and empathetic translator in Muhammad Umar Memon. Naiyer Masud: Collected Works, edited and translated by him (Penguin Classics, 2016) is a wonderful repository, at once engaging and absorbing and carrying with it all the delicacy and subtlety of Masud’s Urdu originals. An erudite Introduction by Memon and an extremely illuminating interview with Asif Farrukhi, coming at the beginning and end respectively of this collected works, throw ample light on the occasionally mystifying contents of the book. They help the reader enjoy this unique kind of writing more fully, a writing that has few sign posts, that is self-referential as few other fictional writings and, yes, even occasionally self-indulgent. These “fragments of consciousness” as Memon calls them, follow the reader long after the story has ended “like a shadow, yes, but suggestive in their fractured imagery of some presence somewhere in the beyond”. For me, an enduring image was of the girl with the crushed feet who sat propped up against a tree in a house, a tree that shed its tiny yellow leaves all over the girl. Who the girl was or why her feet were crushed, or even why she sat under a tree as it shed its tiny yellow leaves all over her, is irrelevant; what stays is the image and the language it is clothed in. Immaculate, precise, spare, and completely shorn of adjectival excess or rhetorical flourishes. And yet, strangely, lyrical too.

Some stories, most notably the early stories from the collection Simiyan have a child-like lack of guile and probing. In fact, Masud wrote Simiyan when he was 12-years old; he rewrote it and added substantially to its details later. In most stories, people go for long walks, enter crumbling homes, stay on for what turns out to be years, live lives that require a complete suspension of disbelief; what they eat or do in ‘real’ life is seldom of any consequence. Despite the pile-up of details and the minutiae of inexplicable phenomena, there is never a straight retelling of actual events. Memon likens the experience of reading a Naiyer Masud story to “walking into a maze with no possibility of ever getting out. A hypnotic circularity, a curling back upon oneself over and over again.” After reading some, if not all the 35 stories included in this Collected Works, the reader will find there is indeed no way of getting out of the maze; what is more, the maze begins to feel like a wonderful place to be.

Here’s hoping that Naiyer Masud, released from a long and debilitating illness, is happy where he is: in a maze with no beginning and no end in sight.

Read e-books by Naiyer Masud here.

Also read Rahman Abbas’ obituary on Naiyer Masud here.