The importance of Shayara’s case for women of all communities

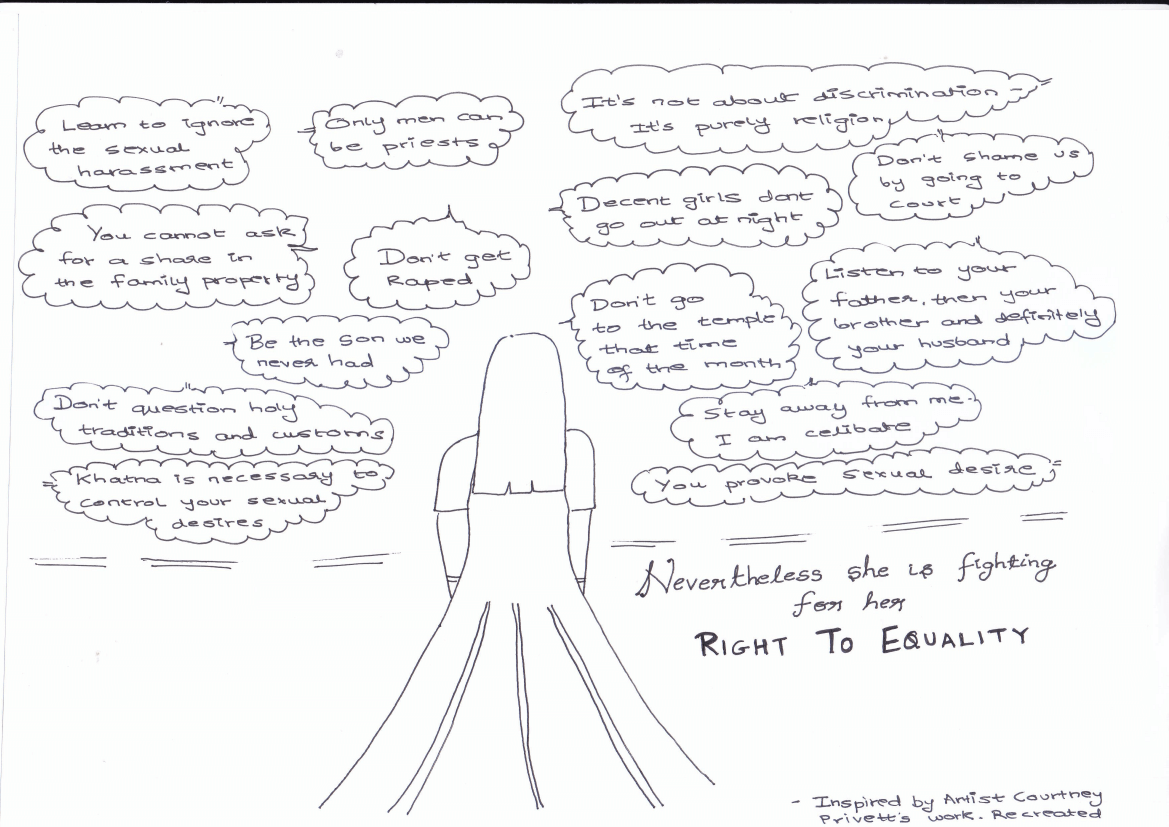

While there has been a state of near hysteria over the issue of triple talaq in the media, no one is clear on the real importance of the case. While the media is flooded with stories of husbands giving unilateral talaq to their wives on the phone and by SMS, no one talks about the fact that women of all religious communities face domestic violence and that women are abandoned without notice. The fact is that inequality in what has come to be known as personal laws exists across all religious communities. Not a single law of any community or tribe is immune from the charge that it violates fundamental rights of women to equality. Agricultural land in many states notoriously is often not held by the daughters of the community. We have only recently seen an agitation in Nagaland for the inclusion of women in municipal councils that failed. The demand was resisted on the ground that legislation could not interfere with tribal customs. The Supreme Court in Madhu Kishwar & Ors v. State Of Bihar & Ors (1996 SCC 5 125) when confronted with the issue of whether tribal customs could be challenged on the ground that they violated fundamental rights dodged the issue by stating that: “For in whatever measure be the concern of the court, it compulsively needs to apply, somewhere and at sometime, brakes to its self-motion, described in judicial parlance as self-restraint…under the circumstances it is not desirable to declare the customs of tribal inhabitants as offending Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution…”

Similarly in Githa Hariharan v. Reserve Bank of India (AIR 1999 SC 1149), the Supreme Court was asked to strike down Section 6 (a) of the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956. The court refused to do so and preferred instead to “read down” a blatantly discriminatory law that said that the father is the natural guardian of the children and it is after the death of the father that a mother becomes the natural guardian. The Supreme Court interpreted the provision to mean that in the absence of the father or when the father was not in charge of the affairs of the minor either due to an agreement between the two parents or if the father for any reason was not able to take care of the child, the mother would be the natural guardian even during the lifetime of the father. Personal laws have become an island within the Indian Constitution immune from any challenge on the ground that they violate the right to equality of women.

In the triple talaq case the Supreme Court is confronted with this question yet again and it remains to be seen if they will decide the question or dodge it by saying that Islam itself does not recognize triple talaq and hence, there is no need to decide the larger issue of whether personal laws are amenable to constitutional checks and challenges. What is at stake is not just Muslim Personal Law but all laws governing marriage and divorce, including Hindu Law. Will the ruling party that is moving towards a Hindutva State, allow such a challenge is the question. For now the Union of India has committed itself to the challenge but may remain content with the striking down on the ground that it is un-Islamic as some groups have argued. There is a lot riding on this case, not just talaq. The issues are fundamental to constitutional gender justice for all women.

Impact of Triple Talaq

The undisputable impact of triple talaq is that it alters the civil status of a married woman in a unilateral manner, as it is the husband who pronounces a woman financially unstable if she is solely dependent on her husband’s income and is primarily responsible for the household chores. Such a woman may be driven to claim maintenance if the mehr (amount of monetary security usually determined at the time of marriage which is given to a Muslim woman at the time of divorce) she receives is nominal which most often it is. She may have to engage in legal battles for the custody of her children. It is ironic that the supporters of triple talaq claim that triple talaq cannot be a subject for adjudication before courts of law and shall continue to remain extra-judicial, but fail to notice that the consequences following triple talaq are adjudicated before courts of law.

Stand of the Jamiat Ulama-I-Hind

Legitimate claims, of violation of fundamental rights to equality, life and dignity of Shayara Bano and of several other women like Inayat and Tamana who have been thrown out of their matrimonial homes, left financially unstable, and cut off from seeing their children by means of triple talaq who are being represented through a collective voice of Bebaak Collective, are receiving backlash from conservative groups such as the Jamiat Ulama-I-Hind for taking the matter to court who are of the opinion that – “Part III of the Constitution does not touch upon the personal laws of the parties and therefore their constitutional validity cannot be questioned.”

Stand of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board

The All India Muslim Personal Law Board represented by Senior Advocates Kapil Sibal and Raju Ramchandran and several others reacted on similar lines taking the stand that– “(Muslim) personal laws cannot be challenged by the reason of fundamental rights” cautioning the Supreme Court not to interfere in the personal affairs of the Muslim community. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board in its written submissions to court states that: “it is clear that though pronouncement of talaq thrice at one go is undesirable but in view of the aforesaid verse of the Holy Quran, it is clear that three pronouncements, howsoever they may be made result in valid dissolution of marriage.”

Law Commission of India on a UCC & UP State Elections

Apart from responses and counter responses of parties to the court case, during the pendency of the matter before the Supreme Court of India, we also saw orchestrated debates on electronic media “liberate Muslim women” and no less than the Law Commission of India issued a questionnaire asking for Yes/No answers to the question “Are you aware that Article 44 of the Constitution of India provides that the State shall endeavor to secure for the citizens a Uniform Civil Code throughout the territory of India? Do you agree that the existing personal laws and customary practices need codification and would benefit the people?” In a well written letter some of us from the women’s movement asked the Law Commission of India to give us a draft of the so called code before we could answer the question, elementary to say the least.

Then came several election promises made by the BJP in Uttar Pradesh that they would end the practice of triple talaq and after the results we were told that Muslim women voted for the BJP as they wanted an end to triple talaq. It remains a mystery how the secret ballot cast by women became part of political propaganda.

Is the insistence on saptapadi (seven steps around the holy fire) among Hindus for a valid marriage being abolished by a Uniform Civil Code? Does polygamy exist only among Muslims or is there de facto polygamy among Hindus as well? Will marriage among all communities be secularized and be truly considered as “a civil union” and “a partnership of equals, and no longer one in which the wife must be the subservient” as suggested by the Verma Committee or are we focused only on the abolition of triple talaq among Muslims? If the latter is the case, the political agenda behind the government championing the cause of Muslim women falls under doubt.

This is not to suggest that formal inequality can continue to exist under the Indian Constitution but rather that all forms of inequality formal or de facto in all communities must be abolished. The fact is that Hindu Law contains the remnants of Manu’s Laws (an ancient sacred legal text followed by Hindus) and that too must change.

Bebaak Collective’s stand in distinction to the Union’s stand

Bebaak Collective issued a statement putting the issue squarely in a secular context against the stand of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board responding as follows:

“First, whether the practice of unilateral triple talaq is validated by religion or not is not our contention, rather it is gender discriminatory and epitomises patriarchal values and therefore must be abolished should be emphasized. Second, the belief that women lack decision making qualities dilutes the citizenship rights of Muslim women in India who have been exercising their electoral rights for more than sixty years now…It is no surprise that All India Muslim Personal Board has not progressed over the decades and reiterates the same position which reverberates the patriarchal conservative ideas of the community. However, we envision a gender just law for the community where women’s question of social security and rights promised by the Indian Constitution will be practised.”

Organizations like Bebaak Collective distinguish themselves from the ruling party in that they articulate the voice of secular Muslim women. They demand not just an end to triple talaq but also social welfare schemes for destitute women. We all know of the notorious problems with Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 and the difficulty of recovering any money form a disappearing husband even when an order is passed for maintenance. Bebaak Collective demands better living conditions, the right to secular education and other benefits from the State for all women. Relief form triple talaq alone will not solve the problem, they want to negotiate for a more equal space for all women within the marriage, they demand and end to domestic violence.

Hasina Khan, founder of Bebaak Collective is of the view that:

“None of the personal laws are gender just. Even Muslim personal law is discriminatory and does not provide equal status to women. Muslim women are doubly oppressed; they witness violence of different forms. State must provide social security to Muslim women who are survivors of any form of violence and discriminations. The State must protect their right to livelihood and also provide community centers, compensations, stipend, library centers, legal aid or counseling sessions to help them with sustenance of their life. The State must provide job opportunities and all kinds of support including working women’s hostel, shelter homes and specialized skills which have market demand to the young women across all communities who can carry forward their life with dignity and independence…We have felt the need to focus on four key issues a) Right to Citizenship and equality, b) Social security, c) Emerging Right wing forces and d) Implementation of Sachar Committee Report… It is seen that a woman has lesser social security irrespective of her community or religious status, we must demand for all of them having emphasis on Muslim women….”

They argue that all personal laws are capable of being challenged on the ground that they violate fundamental rights regardless of whether they are based on religion or custom, are codified or un-codified.

Article 13 of the Indian Constitution states that “all laws in force” in the territory of India immediately before the commencement of this Constitution, in so far as they are inconsistent with the provisions of this Part, shall, to the extent of such inconsistency, be void and the State shall not make any “law” which takes away or abridges the rights conferred by this Part and any law made in contravention of this clause shall, to the extent of the contravention, be void. Article 13 (3) defines the expression “law” to “include(s) any ordinance, order, bye-law, rule, regulation, notification, custom or usage having in the territory of India the force of law” and the expression “laws in force” to “include(s) laws passed or made by a Legislature or other competent authority in the territory of India before the commencement of this Constitution and not previously repealed, notwithstanding that any such law or any part thereof may not be then in operation either at all or in particular areas.”

Bebaak Collective and CSS argue that all personal laws are “laws in force” and must meet the challenge of Article 13. The system of personal laws originated in British India prior to the enactment of the Indian Constitution. Right from Warren Hastings Plan of 1772, Maulvis and Pandits (religious priests) were assisting and advising the courts on disputes governed by Muslim and Hindu Laws. While today priests no longer advise the courts, the system of governing people of different religions by different laws continues till today.

The basic defining feature of any law is that it is binding on citizens and is recognized by the State as law and enforceable by the State. Personal laws are binding on citizens and even today are recognized and enforced by the State. The State has explicitly recognized personal laws in form of legislations for example, Muslim personal laws have been provided recognition through the Muslim Personal Laws (Shariat) Application Act 1937 and Hindu personal laws through various legislations such as Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, Hindu Succession Act 1956, the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act 1956, the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act 1956.

There is therefore no basis for the demand that the Supreme Court exercise judicial restraint in Shayara Bano’s petition.

The Bombay High Court vide a two-judge bench in the case of State of Bombay v. Narasu Appa Mali (AIR 1952 Bom 84) way back in 1952 while upholding the constitutional validity of Bombay Prevention of Hindu Bigamous Marriages Act, 1946 made an observation that the expression “personal law” has not been used in Article 13 and therefore the framers wanted to leave them outside the purview of Part III Fundamental Rights of the Constitution. Later, the Supreme Court in Krishna Singh v. Mathura Ahir (1981 3 SCC 689) while dealing with a case of succession rights of a mahant (ascetic) said: “Part III of the Constitution does not touch upon the personal laws of the parties”. This erroneous decision of 1952 is what the All India Muslim Personal Law Board relies on. Several learned authors have pointed out that no reasons have been provided for this observation made by the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court. Moreover, in a subsequent judgment of C. Masilamani Mudaliar v. Idol of Sri Swaminathaswami (1996 8 SCC 525) the Supreme Court has held: “Personal laws are derived not from the Constitution but from the religious scriptures. The laws thus derived must be consistent with the Constitution lest they become void under Art. 13 if they violate fundamental rights”.

Stand of Bhartiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA)

BMMA has taken the view that after the Delhi High Court case of Masroor Ahmed v. State (2008 103 DRJ 137), talaq-e-bidat/instantaneous triple talaq “has lost its instantaneous nature, as also its irrevocable nature. Thus, even when instantaneous talaq is pronounced it will not immediately effect divorce…courts in India have by a purely interpretative exercise held that talaq-e-bidat or instantaneous talaq is illegal and ineffective. If the same declaration is given by this Hon’ble Court by a process of interpretation of personal law, then the question of going into the constitutionality of personal law does not arise. In the matters pending before this Hon’ble Court in none of the cases the facts comprise of anything other than women being aggrieved by instantaneous talaq and therefore those issues are also academic.”

They argue for a minimalistic approach and request that the constitutional issue of whether personal laws are amenable to challenge and checks in courts not be decided.

Stand of the Union

The Union in its affidavit to the court seems to be supporting Shayara Bano’s petition when it states that “It is extremely significant to note that a large number of Muslim countries or countries with an overwhelmingly large Muslim population where Islam is the State religion, have undertaken reforms in this area and have regulated divorce law and polygamy”. But women’s groups are skeptical of a hidden Uniform Civil Code agenda that may be forming the basis of such support. In February before the U.P State elections, the Law Minister made a statement that “The government may take a major step to ban triple talaq.” No such step has been taken, instead the ball has been thrown into the Supreme Court and the Suprme Court itsef has chosen to give this case a priority hearing on the ground that “the rights of many persons will be affected”.

The real significance of the case: Are personal laws, regardless of which community, immune from constitutional challenge ?

The broader constitutional issue of importance is whether unlike any other laws that are amenable to constitutional challenge for being violative of rights to equality and dignity, are personal laws – be it of Hindus, Muslims, Parsis or Christians – immune from constitutional checks and can they continue to be practiced despite being discriminatory, patriarchal and against fundamental rights of women or any other person for that sake?

What Stand will the Supreme Court of India take ?

Shayara Bano’s petition has now been listed to be heard by a constitutional bench of five judges during the Supreme Court vacations in May. The reason being that the Chief Justice believes that “the matter is of substantial importance” and deserves undivided attention of the court. Only time will tell if the Supreme Court chooses to overrule the Narsu Appa Mali and Krishna Singh cases or chooses to exercise judicial restraint declaring instead that triple talaq in the form in which it is practiced is un Islamic leaving undecided whether personal laws can be challenged. If they do decide that personal laws can be challenged, it will have far reaching consequences for all women regardless of the religion they belong to and advance the goal of gender justice for all.