K.G. Subramanyan (1924–2016) is easily one of the most influential figures in modern Indian art. The wide range of eulogies written since his death on June 29, at the age of 92, is testimony to the legacy he has left behind, and the people he inspired through his art and teachings. Subramanyan’s art, seen through the multiple mediums and genres he traversed, reflects his versatility; he was not only an artist, but also an educationist, poet, storyteller and design consultant. Here, artists Saba Hasan and Gulammohammed Sheikh discuss his legacy.

K.G. Subramanyan, detail from ‘Anatomy Lesson’ / KNMA

K.G. Subramanyan, detail from ‘Anatomy Lesson’ / KNMA

Saba Hasan

Along with the painted faces of Mayyazhi dancers you can see the early influences of French surrealists in his work, as well as the Dada movement… Working with a variety of materials he erased the line between art and craft, and practised in many media outside the elite academic realism of the day. He illustrated several children’s books, made toys, textiles, terracotta relief tiles, clay sculptures, glass paintings, and was wonderfully versatile and free!

Gulammohammed Sheikh

Students would often rush to him wherever he was sitting. Some would later recall how he taught structural design by drawing diagrams on cement floors with chalk or charcoal (and if it happened to be a dusty ground, he would draw with his fingers!)…

From 1959 to 1961 Subramanyan shifted base to Bombay to join the Weavers Service Centre at the instance of Pupul Jayakar. Once there, his improvisatory instincts opened a new chapter in the textile history of modern India. He discovered large stocks of inexpensive plaid lying unsold. In this so called Bleeding Madras textile the reds and blacks would bleed, so he adapted a technique of discharge printing upon the checkered plaid, and superimposed fluid patterns upon it to create a gestalt of mixed layered patterns. The stunning result became so popular nationwide and abroad that the government earned a great profit from its sales. I remember how we all sported Bleeding Madras shirts those days…

When the Black Partridge Art Gallery in Delhi invited him for a group show during the Emergency he sent them a hand crafted hemp peacock, a limp national bird. During the ‘textile’ years, it can be assumed that his active engagement in the craft practices deepened his conviction in the fundamental interrelationship between art and craft practices, and bonding with weavers and printers must have strengthened his firm belief in their innate inventiveness…

As though this enormous output were not enough, in 1990 he embarked upon a massive mural on the outer walls of a building he used during his stay in Santiniketan. Sporting a straw hat to avoid the midday sun, he climbed a bamboo scaffolding several meters high for weeks together, painting the walls, and changed the very body of the building. Now peacocks perched on windows, birds flew, monkeys jumped and palms grew on what had been blank walls. Three years later, he geared up again to finish parts of the walls, a storey and a half of which he had left blank.

It looked as though a magician had converted the building into a miraculous, black and white monument. With the passage of a decade or so, when these images faded and rubbed off, he returned in yet another bout of inexplicable energy to bring the walls back to life by rejuvenating the animated imagery. Now, goddesses sprouted and presided over larger walls, a buffalo demon—Mahisha—sprang to life, the black and white forms played hide and seek all over doors and windows, and the building turned into a mighty udan khatola about to take off…

Following the practice in Santiniketan, the Fine Arts college in Baroda organised an art fair every year. For this, Subramanyan would make toys, write, illustrate and publish childrens’ books and occasionally paint theatre props. He would make tiny animals in pressed clay or assemble pieces of wood, cover them with rexine or leather to construe little rhinos or rams. Many of us still preserve these as cherished gifts of the master. It is said that if a student on his birthday happened to go and meet Nandalal Bose in Santiniketan, Master-moshai would make a drawing on a postcard as a gift to the student.

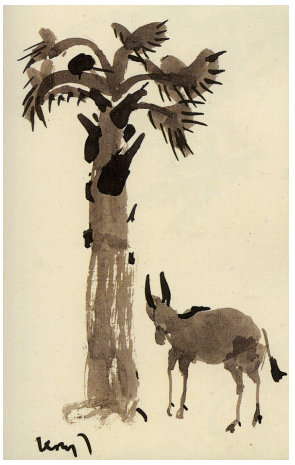

For decades Subramanyan sent hand-drawn greetings on Diwali or the new year from Santiniketan or Baroda, invariably, wherever he might be, to his friends and loved ones, including his erstwhile students. Some would get a peacock, others a myna or a crow, a robust donkey or a mischievous monkey, each with their characteristic movements. Some received images from the arboreal world—a laburnum or a solitary palm. The myriad forms of the lived world animated by his swift and spontaneous brush strokes continue to amaze onlookers, yet.

Extracts from an essay titled ‘The World in Many Guises’, first published in the catalogue for War of the Relics and Recent Works on Paper by K.G. Subramanyan (Seagull Books), held at Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata, in 2015.

See here for a 2014 interview with K.G. Subramanyan.

Two conversations with the artist:

At the 2015 Kochi-Muziris Biennial

With noted art historian and critic R. Siva Kumar / Sahapedia

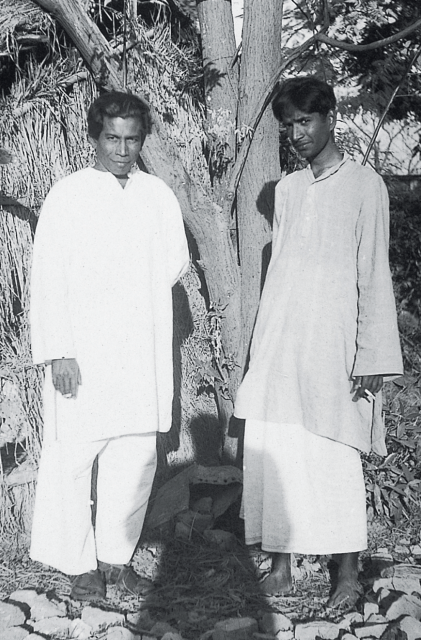

With Ramkinkar Baij / Seagull Books

With Ramkinkar Baij / Seagull Books